The dawn of a new decade in mid-century Galveston belied nothing about what the 1950s would eventually muster. Although its downfall would come seven short years later, the Free State of Galveston era was at its pinnacle in 1950, having carried the island through the Great Depression and World War II to achieve worldwide fame as a luxury resort destination complete with high-glamour (and high-dollar) nightclubs, celebrity sightings, and underground casinos.

One would imagine that a municipal government so besotted with the Maceo enterprises would rest easy on their laissez faire laurels, but Salvatore (Sam) and Rosario (Rose) Maceo established a precedent that demanded more from city officials.

From the outset, Sam and Rose possessed not only a deep affection for Galveston, but also an innate understanding that the success of their most lucrative undertakings, illegal gambling and liquor, were dependent upon the subsequent growth of the city’s legitimate enterprises.

They founded the Galveston Beach Association in 1921 to promote the island and draw visitors and established an array of legal entertainment venues on the Seawall. Following their lead, the City of Galveston coat-tailed on the economic and population boom prompted by the Maceos’ success and endeavored to expand Galveston’s national prominence on the harbor side as well.

Few city leaders were more adept at this silent expectation than Mayor Herbert Cartwright, whose proclivity for diplomacy and negotiation was almost as impressive as his willingness to insulate the Maceos. Likewise a visionary, Cartwright led efforts to widen Broadway Avenue into the major thoroughfare it is today, secured funding to build the bridge to Pelican Island, and convinced two contractors from the east coast to finance the millions needed to raise the grade of the sister island so it could be used for industrial development. He also managed to convince the international giant Lipton Tea to build a plant on Water Street (present-day Harborside Drive).

Even before he was elected mayor, Cartwright had dismantled private ownership of the wharves and transferred them to the city to be overseen by the Wharves Board. For a period during Cartwright’s record five terms as mayor, Galveston’s wharves were some of the only profitable municipally owned wharves in the country.

As the self-appointed Chair of the Wharves Board, landing Lipton Tea further affirmed his policies. However, the official story of how he accomplished this feat leaves out a few choice details.

On the record, Cartwright had already mounted a campaign to bolster the city’s harbor holdings when he met Eric R. Feasey, Executive Vice-President of Lipton Tea, as he was passing through from Houston to New Orleans in search of a Gulf location for a Lipton plant. The company had long coveted a spot along the Gulf—it provided the same unadulterated access of the Atlantic as the East Coast with the added benefit of easier access to the western interior portions of the United States.

These were the features that made Galveston a commercial success in the late 19th Century, but the opening of the Houston Ship Channel in 1914 and the subsequent takeover of the wharves by the Sealy and Kempner families had suffocated international commerce.

Galveston had managed to retain some of its status as a cotton exporter, but the Maceo era emboldened city leaders—Cartwright especially knew how to “sell” the whole town. The breadth of Galveston’s entertainment sector was amply more compelling than the modest trappings of an aging, all-but-abandoned port, and it was unabashedly used to incentivize prospective industry titans.

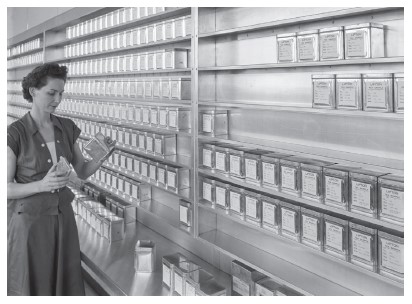

In May of 1949, Feasey completed a 10-day survey in Galveston and then returned to Lipton headquarters in Hoboken, New Jersey, to present his findings to the board. Over the next several months, Cartwright and Lipton executives made countless trips between Galveston and Hoboken to negotiate, while the newspapers whispered rumors of the 250 jobs the plant would provide as it processed and packaged imported tea from “Asiatic” countries. Finally, on August 7 it was announced that Lipton Tea would establish a $500,000 district plant to be in operation by March of 1950.

By September, plans were finalized and the land on Water Street between 18th and 20th Streets was being leveled. On September 16, the final draft of the contract was sent to Hoboken, and from there it would travel to company headquarters in London.

The deal was more than amenable for Lipton. The construction on the wharves would be financed by the city and then held under lease by Lipton Tea Company for final acquisition by the company.

Additionally, a 40,000 square-foot warehouse would also be constructed as a Wharves Board project and leased to Lipton. Far surpassing the original estimate, the entire project came in at just under $1 million.

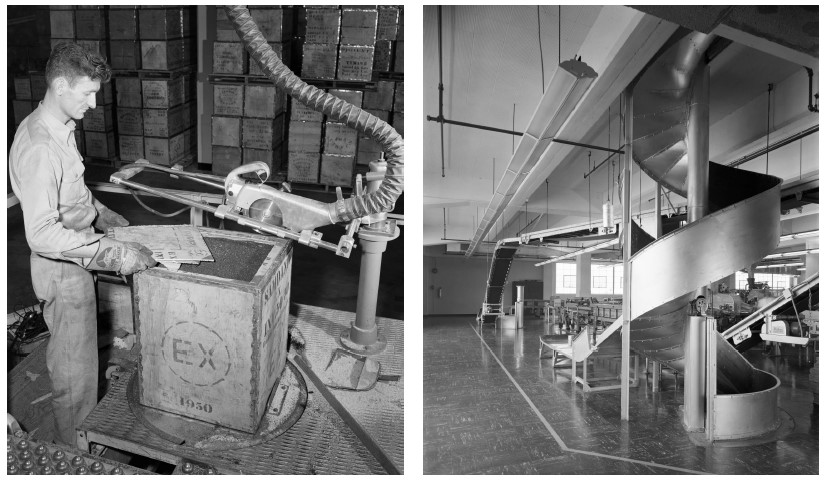

Tellepsen Construction Company was awarded the contract for the large, 5-story plant at the foot of 19th Street. Excavation began on January 18, 1950. The plant was built in sections and a cascading sequence of pilings, foundation, and then the building.

Special equipment was brought in to hammer pilings 44 feet below mean low tide. When the pilings on the first section were complete, the foundation was then laid immediately on that section at the same time piling work began on the second section, and so on with the ensuing sections and phases until the building was completed in early fall.

Many cities contended for Lipton’s Gulf plant, and mainstream history should certainly credit the city’s advantageous offer and its abundant availability of waterfront property that allowed Lipton to process and package tea directly off the boat from Ceylon, India and other areas of the Far East. But in 1979, a long-retired Herbert Cartwright gave a candid interview with Alan Waldman for In Between magazine that revealed a lesser-known version of the story of how Lipton chose Galveston.

Although not controlled by the Maceos, a notable part of the Free State of Galveston was a red-light district on Postoffice Street that existed for nearly 70 years. Gracefully rounding out the city’s trifecta of vice, “The Line” was inhabited by shrewd, ambitious madams who curated high-end houses to appeal to wealthy, high-society clients during a time when prostitution was deemed a “necessary evil” due to the societal constraints placed upon sexual relationships between men and women of certain stations.

Operating on a de facto basis, the most successful madams were the ones able to maneuver the political systems in place to minimize inevitable interference by law enforcement.

Mary “Gouch-Eye” Russel became one of the most successful madams in Galveston not only due to her exclusive employment of beautiful college-age girls, many of whom were saving their earnings for actual college, but also because of the strong alliance she forged with Mayor Cartwright. As with the Maceos, Cartwright’s relationship with Russel proved itself more than once to be symbiotic.

“I began getting him dates with good looking gals,” Cartwright said of Lipton exec Eric Feasey, “and before you knew it we were going to New York, and he was coming down here and things were finally at the contract stage. We were going to sign the contract on a Sunday morning, and old Feasey blew into town that Thursday. It didn’t take long to line up some gals for him."

“I began getting him dates with good looking gals,” Cartwright said of Lipton exec Eric Feasey, “and before you knew it we were going to New York, and he was coming down here and things were finally at the contract stage. We were going to sign the contract on a Sunday morning, and old Feasey blew into town that Thursday. It didn’t take long to line up some gals for him."

“He said that since we were going to finally sign the contracts, he wanted us to find him a really smoking gal. So we went to Mary Russel, one of the old time madams who really knew the score, and she got us a gal out of Dallas. About 19 or 20 years old. (Feasey was in his early 50s). We took her to Nathan’s [Department Store] and spent $2000 on her clothes for the weekend. She had beautiful manners, spoke English real well, and was a knockout."

“Anyway, we passed her off as a Sunday school teacher, and he took her off to the Galvez, where she must have really put it to him. When I picked him up Sunday morning, he said we did ourselves proud: she was a wonderful girl. He said she had gone to teach Sunday School and would be back soon, so we had to get down and sign the contract quickly…which we were happy to do.”

The Lipton Tea Plant operated in Galveston for just over forty years. In November of 1990, the company announced its closure, citing, “large requirements for capital expenditures within the Galveston plant, greater efficiencies available at our other larger plants, sales forecasts and transportation costs to supply products to our large customers and raw materials to the plant.”

Controversy erupted over the closing, with city leaders blaming the Galveston County Appraisal District for Lipton’s decision. The CAD had released a bloated assessment of the plant, raising the taxable value of the plant’s property and equipment from $4.5 million to $9.5 million in one year.

A valiant effort was set forth by City Councilman Mimo Milosevich to keep Lipton in Galveston. He rallied under the banner of the “Galveston Tea Party,” structured a $7.9 million incentive package, and actively courted company executives, even encouraging them to file a lawsuit against CAD.

But on November 24, 1990, Lipton announced that the money saved at a CAD hearing would not offset the court fees, and they dropped the suit. Milosevich simply did not have the finesse—or was it the favors—of Cartwright. The plant closed its doors on March 31, 1991.

On December 18, it was sold to the Sealy & Smith Foundation for $1.5 million, barely more than the city paid to build it forty years prior, and substantially less than its appraised value. The foundation then donated the building to the University of Texas Medical Branch. It still stands today at 1902 Harborside Drive.