Even before the Key-Harriss house was built, a prominent citizen of Galveston lived on the property. Dr. John Fannin Young Paine (1840-1912) and his wife Elizabeth Estes (1855-1937) lived in a home on the lot from 1884 to 1910. The physician was a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas Medical Branch and a practicing gynecologist and obstetrician at John Sealy Hospital. Dr. Paine moved his practice into the home during the final year that the couple lived in this location along with their daughter Erin and her pet Mexican parrot.

For the following two years, the doctor’s former home belonged to Reuben Gordon, a sales manager for Miller & Vidor Lumber Company. His wife Mabel ran a boarding house and offered table boarding (meals only) in the residence. Lodgers included Reverend Haywood Lewis Winter, the new rector of Grace Episcopal Church. When the couple’s fourth child arrived in 1912, they moved out of the house, and it was demolished.

In 1914, Brewer W. Key (1859-1922) and his wife Julia Vedder (1859-1919) built their dream home at the prestigious address. His positions as the president of Security Trust Company, president of Gulf Lumber, vice-president of City National Bank, and president of York-Key Lumber in Oklahoma afforded them the financial advantage to create an impressive, modern home where they could entertain family, friends, and work associates.

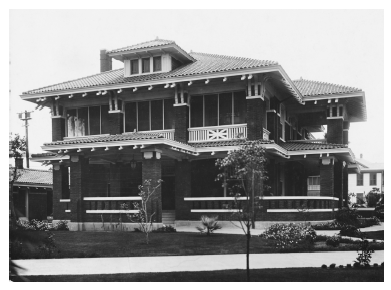

A two-story Spanish Mission-style creation, the home was considered the height of 1920s design. Impressive for its size alone, the residence covered three lots on the most desirable avenue in Galveston. Each detail added to its elegance, including the tile roof, tin-lined wooden gutters, and gently scrolled wooden brackets beneath the eaves. The double-hung windows were outfitted with stone lintels inset above and stone ledges below.

Stone steps led up to the most expansive outdoor entertaining area: a long, L-shaped, tile-floored porch that wrapped from the front of the house around the side and connected with a porte cochere with stone wheel guards at the corners and stone coping. The family could look left from the front porch to the home of their neighbors the Moodys or right to admire the towering Texas Heroes Monument.

As visitors to the home crossed the front porch, they entered leaded glass doors with leaded glass sidelights and transoms in copper settings. From there, they crossed the threshold into an entryway hall floored with maple and admired a grand staircase with birch railing and spiral newel. A half-bathroom for guests was discretely tucked beneath the stairs, removing the necessity for callers to ascend to the second floor during events.

A 17’ x 25’ living room was to the right of the entryway, featuring the same maple flooring but crowned with a Spanish-style wood-beam ceiling. Carved wood mantle columns flanked each side of the fireplace adorned with a Rookwood-tiled surround and hearth, and each side was decoratively topped with a frieze ornament.

An identical fireplace anchored the adjacent dining room, accessed through double doors in the parlor. Here, the maple floors were paired with wood wainscot and a plaster ceiling featuring an elegant cornice.

Dinner guests here were served via the adjoining butler’s pantry with built in cabinets and a broom closet. Other pantry doors led to the kitchen and the breakfast room with its maple floors, built-in window seat, and canvas and wood wainscot.

The kitchen was attractive but designed for functionality, featuring pine floors and water-resistant cement wainscot, a fashionable German silver (nickel silver) backsplash and stove hood, and an enamel Wolf stove.

Two side doors from the kitchen led to screened porches: one with a wooden floor and cement steps into the lawn, and the other with a cement floor and a stairway to the basement storage areas. Outside the kitchen window was another set of cement stairs with a pipe handrail, which lead to the exterior basement door and accessed the coal room.

Double doors from the breakfast room opened onto a third screened porch, this one elegantly lain with a quarry tile floor and probably utilized for visits with family and close friends. A back staircase from a rear hallway led to meeting the landing of the front, public staircase.

One of the most notable features from the exterior of the home was the second-floor balcony that extended over the front entrance. This opened into the 16’ x 12’ play room that shared a bathroom with the guest bedroom, which had its own fireplace.

A central hallway upstairs led to the primary bedroom, children’s room, and maid’s room, and featured a scuttle opening access to an attic. All the upstairs bedrooms shared one, tile-floored bathroom, accessed through separate doors and up a six-inch riser step. It was tastefully equipped with a marble-based toilet, bathtub, and sink.

The grand 19 ½’ x 14’ owner’s bedroom had a special alcove with an L-shaped window seat surrounded with windows, and a private screened sleeping porch with plastered walls. Across the hall were the children’s and maid’s rooms, which shared a screened sleeping porch with a canvas covered floor. Because the Keys had no children of their own, children’s areas of their home were never used for their intended purpose, but provided enjoyable spaces for visiting family and friends.

The couple dedicated themselves to each other and their island city and focused their time and energy on causes that benefitted others. Brewer donated three lots to be used for a nurses’ home across from St. Mary’s Infirmary, thousands of dollars for improvements to Cahill Cemetery (now part of the historic Broadway Cemetery District), financial means for local students to attend college, and funding to purchase additional lots so that new buildings and playgrounds could be built.

Julia was a life member of the Young Women’s Christian Association and an active volunteer. When she passed away in 1919, her husband donated $70,000 for the establishment of the Julia Key Memorial Young Women’s Christian Association Home which was formally dedicated in December 1921, just one week before his own death.

At the time of his passing, Key was supporting three students in various colleges and had made a half a million dollars in bequests throughout the city in the months prior. Among the legacies of his will was $5,000 to Jack Ammons, a longtime servant. It was the same amount he left to members of his own family.

A few months after his wife’s passing, Key made the decision to sell the home that he and his wife had shared for so many years. Baylis Earle Harriss (1883-1926) and his wife Loula Curtis (1884-1955) purchased the residence in July 1920 for $70,000. President of Harriss, Irby and Vose, one of the largest cotton merchandising firms in the country, Harriss also held prominent positions on a number of local boards.

A few months after his wife’s passing, Key made the decision to sell the home that he and his wife had shared for so many years. Baylis Earle Harriss (1883-1926) and his wife Loula Curtis (1884-1955) purchased the residence in July 1920 for $70,000. President of Harriss, Irby and Vose, one of the largest cotton merchandising firms in the country, Harriss also held prominent positions on a number of local boards.

Along with their three daughters and son, the Harriss family brought new life into the home with parties, family celebrations, and community meetings. Their family pets, a white pit bull with brindle spots and a spirited white fox terrier occasionally added excitement by escaping from the home and yard, necessitating newspaper advertisements recruiting help to search for them.

In 1923, Harriss was elected mayor of Galveston and diligently worked to increase commerce at the city port. During a visit to Asheville, North Carolina in the fall of 1926 on business, he suffered a heart attack and died. His wife, son, and one of their daughters, along with their parish priest, accompanied his remains back home on a funeral train which was met at the Galveston station by Mayor J. E. Pearce, city commissioners, and hundreds of Galvestonians.

His body was taken to the Harriss home, where is laid in state in the family living room, attended by an honor guard of third- and fourth-degree Knights of Columbus until the time of his funeral service.

Despite their loss, Loula and her family continued to celebrate happier times in the home, including debutante parties for the female members of the family and other social gatherings. The home was described as being elegant and palatial in local newspaper descriptions of these events.

Loula remarried in the early 1930s to Edward McDonough Benz (1894-1951), a local rancher who was well established in Galveston social circles. Although they occasionally lived in the Broadway home, they spent the majority of their time at his ranch in Harris Valley, so the matriarch deeded the residence to her daughter Virginia Harriss Peek (1910-1980) who was affectionately known as “Aunt Gin Gin” to her nieces and nephews.

In 1946, Peek sold the property for $55,000 to William Wallace, who sold it to James B. Johnston (1910-1956) the following day. During Johnston’s ownership, the large home took on a new purpose as the Johnston Funeral Home. The first floor was utilized as the funeral home, the front portion of the second floor (formerly a children’s playroom) was utilized as a casket showroom, and the upper back rooms became his residence.

In April 1947 Johnston helped to deal with the aftermath of the Texas City explosion, even installing two emergency phone lines to handle the increased number of incoming calls.

The following fall, Selby Young (1917-1993) left his job as an embalmer at Malloy & Son Funeral Home where he had worked for over five years to partner with Johnston creating the Johnston-Young Funeral Home. The two bachelors shared the second floor as their residence.

By the end of the decade the business closed, but Johnston remained in the industry. Strangely (or perhaps fittingly), he died as the result of a heart attack while lifting a casket.

The home at 2525 Broadway housed insurance companies in the 1950s, including the Texas Prudential Insurance Company, but by 1961 became a residential rental property again. Passenger Agent C. L. Sykes of the Galveston-Houston Interurban called the mansion home for only months before the property was demolished, bringing a legacy of elegance and service to the community to an end.