After twenty years of working to prove its viability as a port of

commerce, Galveston

finally had railroad access to the interior. But the celebration of this triumph

was almost immediately thwarted by talk of war. The United

States was nigh a century old, yet it was already on

trial at the court of its ultimate destiny, and the exuberant outlook upon Galveston’s future

justifiably acquiesced to fear and worry as the fragile threads of the young

nation began to unravel.

At first the residents and businessmen of Galveston

were mostly complacent about the onset of civil war in the United States.

“The Island paused scarcely at all in the

conduct of its normal business [and] made only minimal defensive preparations.

(Kelly, p. 26)” Shippers and

merchants on the Strand balked at the idea that anything could dampen the

seemingly inevitable growth of Galveston, even after President Lincoln ordered

an embargo of all secessionist ports on April 19, 1861.

Soon, however, the stark reality of war reared its head. The

Confederacy’s predominant military strategy was defense, their priority being

to protect major territories. In Texas,

this meant that the burden of conflict was effectively transferred onto the

outlying and coastal communities. Galveston in

particular was deemed even more crucial because it was the closest major port

to Mexico,

an ally of the Confederacy.

On July 2, 1861, the peaceful clearance of federal ships into the Port of Galveston

ceased outright with the contested arrival of the naval vessel the South

Carolina. The island was officially a war zone,

and for the next five years Galveston’s sole purpose for existence would be the

defense of its precarious positioning, a plight that would forever alter the

entrepreneurial hierarchy of the Strand.

The first upset of Galveston’s

upper society came at the hands of an evacuating population that abandoned

their island homes to take refuge further inland. Soon after came the

casualties of war, as many prominent Galveston

citizens had taken up arms to defend the South. The ones who did survive their

military service chose to close their businesses until the end of the war.

Such

was the case with several members of the Trueheart family, tax assessors and

collectors who would eventually open the first real estate firm in Texas, located just off the Strand.

Many other businesses, such as the Galveston

Daily News, relocated temporarily to Houston.

Some businessmen, such as J.C. Kuhn, simply abandoned the island completely. In

1861 Kuhn sold three brick buildings on the Strand,

his wharf, and his home; he never returned.

Many high-profile businessmen did remain in Galveston, but in staying true to the cause

they used their assets and connections in service of the Confederacy rather

than private commerce. William Pitt Ballinger, a lawyer with offices on the Strand, abandoned his practice to work as a Confederate

Receiver on the island, and still others used their commercial contacts and

resources to work as purchasing agents and blockade runners for the South’s

cause.

Many high-profile businessmen did remain in Galveston, but in staying true to the cause

they used their assets and connections in service of the Confederacy rather

than private commerce. William Pitt Ballinger, a lawyer with offices on the Strand, abandoned his practice to work as a Confederate

Receiver on the island, and still others used their commercial contacts and

resources to work as purchasing agents and blockade runners for the South’s

cause.

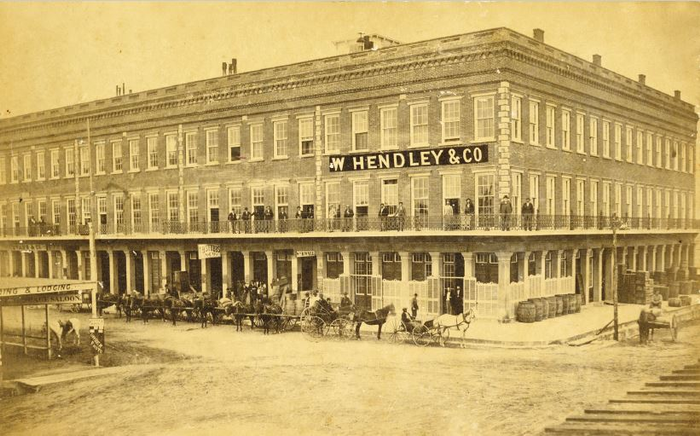

Ebenezer

B. Nichols purchased 2023 Strand (across from

Hendley Row) from Kuhn’s fire sale and relocated his commission house. During

the war The Nichols Building was used by the Confederate general Paul O. Hebert

as his headquarters, while Nichols himself went out and recruited over

eight-hundred men for the Confederacy.

Deprived of its commercial pursuits, the Strand

had become a battlefield. Hendley Row, the tallest building in the city at the

time, was repurposed as a military watch tower as it provided an excellent view

of the federal blockade. Then because of the building’s size and fortitude, it

was adopted as military headquarters, housing soldiers and also becoming the

pinnacle of perceived power. If a regiment wanted control of Galveston, they first had to control Hendley

Row.

Its position along the harbor also made it an easy target, however. The

alley and harbor shoreline had yet to be filled in, and at one time a Union gun

boat sailed right up to the north side of the building and blasted a cannon

ball through its thick brick walls. The scar from that blast remained on the

building for many years and was only recently repaired.

In late 1862 the island was seized by the Union with little fanfare, and

the Confederate forces that once occupied Galveston

vanished, seemingly as uninterested in returning as their commercial

counterparts.

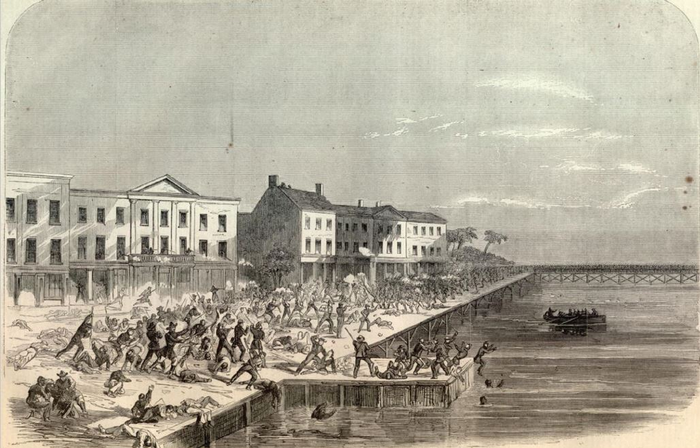

Then, just after midnight on January 1st of 1963, in what is known as

the Battle of Galveston, Confederate troops under the leadership of General

“Prince” John MacGruder launched a surprise attack and reclaimed control of the

island. After that, the island remained in Confederate control until the end of

the war—it was one of only two Gulf coast ports left waving the rebel flag at

the conclusion of the Civil War.

In April of 1865, Generals Lee and Johnston surrendered their efforts to

the Union, and Galveston

officially surrendered a few months later on June 3. A month following, the federal blockade was at last rescinded and after four

years of meager shipments eking in through the maritime barrier, Galveston was

once again free to resume commerce.

The years of conflict on the Strand had

taken its toll and the merciless hands of war had nearly annihilated the city

with its destructive grip. Many of the wooden buildings in the commercial

district had burned or been badly damaged in the battles, as had the wharf.

Some buildings had been torn apart for firewood; homes and businesses were

looted bare—sometimes for supplies, sometimes for fun; Hendley Row had a gaping

hole in its side. Union troops now occupied the island, the price of redemption

known as Reconstruction.

Nevertheless the city somehow managed to stay focused on resurrecting

its status as the commercial center of the southwest, even to the point of

graciously ignoring the presence of the federal military. Even residents who

found themselves on opposing sides just months ago managed to choose civility

and tolerance for the sake of Galveston’s

future. Anti-Union sympathies were considered uncouth and inappropriate to the

current cause. Galveston

could not save the Confederacy, but they could still save themselves.

Nevertheless the city somehow managed to stay focused on resurrecting

its status as the commercial center of the southwest, even to the point of

graciously ignoring the presence of the federal military. Even residents who

found themselves on opposing sides just months ago managed to choose civility

and tolerance for the sake of Galveston’s

future. Anti-Union sympathies were considered uncouth and inappropriate to the

current cause. Galveston

could not save the Confederacy, but they could still save themselves.

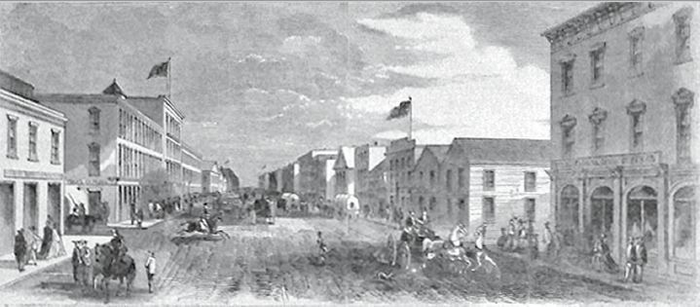

For the fiscal year that ended on August 31, 1866, Galveston’s port handled 375,000 tons of

cargo. The Strand slowly began to resemble

itself pre-war, lined predominantly with wooden buildings. The few brick

structures that survived the war were repaired, but among all of the returns to

its 1850s appearance, a new trend in architecture began to emerge that would

establish the Strand’s now-famous

aesthetic.

The Jockusch building, located on the southeast corner of 21st

and Strand, was built just after the war ended

and has a façade built of iron due to the lack of raw building materials at the

time. John Jockusch had been a resident of Galveston

since 1840 and served as the Prussian Consul to the Republic of Texas.

Twentieth century renovations of his building covered over the original brick

and iron with stucco, giving it a more modern appearance.

In 1866 the McMahan Bank was constructed on the southeast corner of 22nd Street.

A beautiful three-story brick building, it housed the enterprises of Thompson

H. McMahan who had been a prominent banker and merchant in Galveston since the 1850s. It was destroyed

by fire in 1877 and replaced by the First National Bank Building which still

stands today.

The

largest of all of the new structures was the P.J. Willis & Brothers

wholesale grocery house, cotton factory, and commission house. The massive

three-story structure built in 1869 took up the entire block of 24th Street north

of the Strand. P.J. and R.S. Willis were from Maryland and came to Galveston in 1837 where they secured a niche

within the realm of affordable food and clothing products. All that remains

today of their structure is the first floor which has been segmented into

several spaces occupied by the Mediterranean Chef, Crow’s Southwest Cantina,

and Brews Brothers.

In addition to new buildings, new faces arrived after the war as well.

Colonel W.L. Moody, whose name would reverberate through Galveston

for generations, saw not the destruction of Galveston but its potential for wealth and

opportunity.

As the decade drew to a close, the Strand

commercial district would bear the brunt of yet another foe, although this time

it was the forces of nature. Two major fires broke out on the street in 1869

that all but eliminated every wooden building west of 22nd Street. The Moro Castle

Saloon fire originated in one of the first buildings on the Strand, leveling it

and the entire southern block of the Strand

between 23rd and 24th Streets. This included the original

Merchants Mutual Insurance Company Building at 2317 Strand,

a replica of which was constructed in 1870 and still stands.

But as Galveston

had already proven once, and would prove again, it would take much more than

physical destruction to dampen its commercial endeavors. With the antiquated

wooden structures gone, the Strand was now

poised to become a symbol of the city’s outlandish prosperity, and to take its

place in the portals of history as an enduring architectural marvel.

Chapter 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7- 8 - 9 - 10 -11 - 12