Forgotten family heirlooms reveal a mysterious island tale of murder and wrongful execution.

“I didn’t even know my father had a brother,” says Susan Mardis nee LaCoume, a Houston area resident with family ties to Galveston that span four generations. “My mom told us after Daddy died—he had disowned his brother years before we were born. She didn’t really know what had happened except that he always referred to his brother as the ‘black sheep’ who was involved with ‘violence and gangsters.’ My Daddy was in the Navy, so he definitely had strong feelings about such things.”

The revelation, and the story of her uncle Bernard LaCoume Jr., may have remained buried in the sands of time were it not for a discovery which prompted her mother’s explanation. Susan found two manuscripts secreted away in a large chest among her father’s earthly possessions.

One was a large, 8x12, 300-page novel written by Bernard entitled The Flash, about the exploits of a secret service agent and his takedown of a vast and detailed criminal underworld. It was professionally bound and featured two original black-and-white photographs—one of LaCoume on the title page and another of his mother to whom the novel is dedicated.

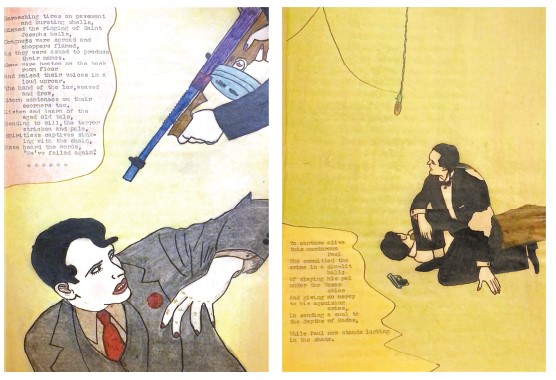

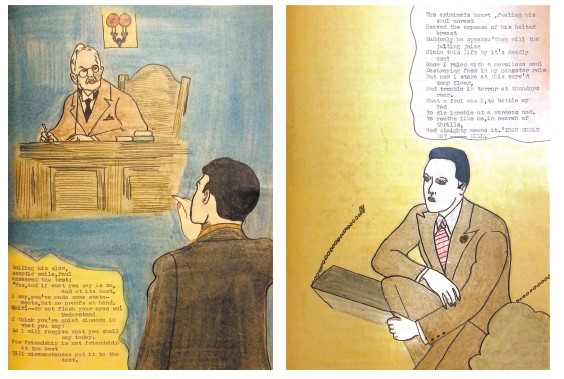

The other manuscript was a thin, 8x10 bound booklet with “The Gangsters Last Throne…” embossed in gold letters on the cover. Inside, full-color drawings accompany a dramatic ballad of LaCoume’s 1934 trial where he was sentenced to death for the murder of a man in Zavalla, Texas, and tucked among the pages of poetry were two chilling newspaper articles.

One told of a desperate petition by Bernard’s parents for a stay of execution. The other recounts the moments before his death in the electric chair.

Also discovered was a typed, unsigned statement which makes convincing protestations of Lacoume’s innocence and recounts the events leading to his arrest, written after his conviction presumably in support of his appeal for clemency. Whether the letter was unsent or merely ignored remains unknown, as does the truth of what exactly transpired during the early morning hours of February 9, 1934.

Although given the title of Junior, LaCoume was in fact named after his grandfather Bernard LaCoume who was born in Crowley, France in 1852 and immigrated to New Orleans when he was 19. A baker by trade, LaCoume Senior moved to Galveston as early as 1881.

In 1884, he opened up his own storefront called New French Bakery at an obsolete address of 168 West Church Street (somewhere along the 2800 block today). He changed the name to the New Orleans Bakery in 1888, operating at various locations throughout downtown Galveston over the next few years until securing a space at 2226 Winnie where he remained until 1904.

Senior sold his bakery that year to Basilio Donati but remained employed at the newly minted Texas Star Bakery until 1908. Donati sold the business to the Martinelli brothers in 1911, and a version of it still exists today at 5425 Broadway Avenue.

LaCoume pursued work at other bakeries around town for more than a decade before becoming a proprietor again in the early 1920s. He opened LaCoume’s Bakery at 1921 Market Street which quickly became known for its fruitcake and ButterKrust bread. Bernard passed away three short years later in 1927, a distinguished and well-respected resident of Galveston.

His grandson and namesake Bernard LaCoume Jr. was a dashing, charismatic young man notwithstanding his penchant for the sensational and criminal. Born in 1913 to Senior’s eldest son John E. LaCoume, a clerk at Merchants & Planters Cotton Compress, Bernard entered his formative years during the early and exponential growth of the Maceo empire and the Free State of Galveston era when the city’s economy was centered around the illicit industries of gaming, illegal booze, and prostitution.

Judging from both his appearance and the later emergence of his hidden talent as an author and poet (a character in The Flash who owned an upscale casino was named Sam Bristow, curiously similar to Sam Maceo), Bernard seems to have become quite smitten with the lore of a criminal lifestyle although the extent of his endeavors is wholly unknown.

Newspapers of the time report involvement in minor crimes and altercations, such as an incident in 1931 where he was attacked and robbed on his way home from the barbershop where he worked, in a fashion that seemed as though he was targeted. News of Bernard’s murder trial in 1934 indicated that he had been arrested on numerous occasions, but the only ones reported were implications in two petty robberies in 1932.

That year, he was arrested for breaking into Ball High School and stealing a typewriter and several silver athletic trophy cups and again for burglarizing Sacred Heart Church of several ceremonial chalices. The loot was later found in an abandoned house on the corner of 24th Street and Sealy, where it appeared an attempt was made to melt down the stolen metals and fashion them into counterfeit coins. Bernard was not indicted in either case, but his luck seemed to run out in 1934.

On February 5, Bernard was approached by his close friend, 20-year-old Roy Cusack, about a foolproof job in Zavalla that needed a third guy. Cusack was enlisted by Glen Warren, a native of Zavalla who was currently living and working in Galveston but had recently returned from a three-week stay in his hometow

Warren spent that time casing his neighbor and longtime family friend, 79-year-old Charles E. Cansler Sr., a well-to-do casket salesman who lived on the land adjacent to Warren’s family farm. He learned that the old man would awaken every morning before sunrise and leave the house to tend to the livestock, which conveniently provided enough time for someone to break into Cansler’s house and steal a safe brimming with cash and bank notes that he kept in his wife’s bedroom.

Since Warren had grown up with the Cansler family, he knew the layout of the house and the exact location of the safe. But the safe was heavy, and Warren needed help.

He returned to the island and attempted to get some “older heads” to assist in his scheme, but all of them declined. So instead he turned to the young and ambitious but directionless Roy Cusack, who became so excited about the robbery that he quit his job. Despite the enthusiasm he conveyed thusly to his good friend, Bernard LaCoume initially did not want to have anything to do with it.

Over the following days, LaCoume went to their mutual friend Frank Pressler and asked him to talk to Cusack and get the idea out of his head, and the details get murky from here. Somehow, despite his insistence that he had still not agreed to do the job, Bernard did end up taking a trip to Lufkin with Cusack and Warren on the evening of February 8. Cusack’s family lived there, and apparently, so did LaCoume’s wife.

Although no mention is given of his wife’s name, nor even her existence outside Bernard’s testimony in court, he testified that when he arrived at his mother-in-law’s house, she conveyed the news that his wife had divorced him. Only then, in a fog of anger and grief, did Bernard agree to go on to nearby Zavalla with Cusack and Warren. They arrived at the Cansler house just after 4am on Friday, February 9.

Lights were on in the home, so they knew Cansler was awake and that their timing was perfect. They watched as he walked out of the house and into the yard and the trio slipped into the house unnoticed.

According to the typed statement found with the manuscripts, Warren and LaCoume were locating the safe while Cusack had located Mrs. Cansler. He gagged her and was working on tying her up with bedsheets when he called out to Bernard to help him.

Unbeknownst to LaCoume and Cusack, the old man had unexpectedly returned to the house while they were in the room with Mrs. Cansler, binding her and covering her with a quilt. Bernard testified that he never even saw Mr. Cansler, but that he and Cusack did hear voices and realized he had returned to the house.

However, when Warren came and found them to help with the safe, he allegedly told them plainly that “the old man had been taken care of,” and both Cusack and LaCoume said they simply assumed Warren had tied him up.

The three carried the safe out of the house, put it in the car, and took off towards Galveston, but they had traveled less than half a mile when the car ran off the road and got stuck in the mud. While LaCoume and Warren tried to free the vehicle, Cusack walked to a nearby “pump station” and stole a car. When they tried to pull themselves out with the stolen car, it got stuck in the mud, too.

Exasperated, Bernard declared that “he had enough of the whole thing” and said he was going back to Lufkin on foot. While passing through Huntington, LaCoume was picked up by the constable and questioned about the stolen car at the pump station.

Bernard later claimed that at this point he still knew nothing about Cansler’s murder, yet overtaken with frustration about the robbery, perhaps angered that he had abandoned the loot, or maybe worried that he would be deprived of his cut, Bernard told the constable that he wanted to talk to the County Attorney.

He was taken back to the station in Zavalla, the place where Bernard claims he first learned about the murder while he was being questioned. Bernard cooperated fully, issued a complete statement of his involvement in the robbery, and gave the constable the names of his accomplices.

Meanwhile, Warren had located a friend from Zavalla to help pull out his car, and he and Cusack made it back to Galveston undetected. They went straight to Warren’s house where they managed to crack open the safe. It contained only four $10 gold pieces.

At Warren’s trial, Mrs. Cansler testified that less than two weeks prior to the robbery, Mr. Cansler had decided to take all of the money out of the safe and put it in different banks throughout Lufkin and Zavalla. After Roy left the house, Warren buried the busted safe in his yard.

On Saturday morning, Warren was preparing to leave the house just as police arrived with a warrant for his arrest. They found the buried safe and identified his car as the one seen near the Cansler’s house.

A few hours later, Roy Cusack was also apprehended. They were both taken to Lufkin, and when they learned that Bernard had been picked up and ratted them out, the two were apparently “very bitter at LaCoume and said they would stick it all on [him].”

On February 12, separate preliminary hearings were ordered for the three men, and the next day they were remanded to the Lufkin jail. Glen Warren was tried first, and more than 25 Galvestonians were called by the prosecution to testify against him.

On March 9 after less than 30 minutes of deliberation by the jury, he was convicted and sentenced to death in the electric chair. Three days later on March 12, the trial of Bernard LaCoume began.

Although no new evidence was presented against Bernard than that of Warren’s trial, and barring the fact that Bernard’s attorneys did not question even one of ten different character witnesses from Galveston offered up by LaCoume, things still seemed to be in his favor—namely, the testimony and statements of Mrs. Cansler.

The morning of the robbery in her statement to police, she said that while she was under the quilt, she heard her husband say, “I never thought I would raise a boy to treat me like this.”

At the trial, she testified that she and her husband rose at 3:30am, and as she started for the kitchen to start a fire, the men came into the room where she was and hit her over the head, stunning her. They tied her hands behind her back and bound her feet, then put her on a bed and threw a blanket over me.

“I heard someone in the next room say, ‘I think I shut that old man’s mouth.’” Since she was covered, she did not know which of the men said it, nor did she seem to identify which of the men attacked her.

“I heard someone in the next room say, ‘I think I shut that old man’s mouth.’” Since she was covered, she did not know which of the men said it, nor did she seem to identify which of the men attacked her.

Settled in the uncertainty surrounding Bernard’s involvement, the defense attorneys were suddenly awash in hopelessness when the prosecution called a surprise witness on the morning of February 14. It was Glen Warren, who took the stand and declared that he saw Bernard LaCoume murder Charles Cansler on the morning of February 9. Bernard’s defense apparently did not ascertain the oddity that this morsel of information was somehow excluded from Warren’s trial, because it was enough for the jury.

Bernard was found guilty and sentenced to death on March 15. A few weeks later, Glen Warren’s death sentence was reversed and he was granted a new trial. On May 9, Roy Cusack was also convicted but sentenced 2-99 years. Either justice was done, or Warren and Cusack got their revenge.

On January 9, 1935, Bernard LaCoume lost in the court of criminal appeals. His parents had worked tirelessly in the months since his conviction leading up to the appeal, spending months gathering signatures for a petition to Governor Miriam A. Ferguson for a commutation of the death penalty to life in prison.

Unfortunately, 1934 was an election year, and Ferguson’s seat was given up to James Allred on January 15, 1935. Despite the family’s continued pleas, Allred’s office announced on August 22 that the governor would not grant clemency to LaCoume.

Bernard LaCoume was executed on August 23, 1935. He was 22 years old. Following his death, another bizarre series of twists emerged in Bernard’s story that further lend to the mystery of who was responsible for Cansler’s murder.

On April 15, 1936, Glen Warren’s appeal for a new trial was reversed and the death penalty was reinstated for unknown reasons. Then, two weeks before his execution on July 31, Warren’s father was murdered by Charles Cansler’s son.

Prior to his electrocution, Bernard gave a long speech about forgiveness from his death chamber. He also wrote about forgiveness extensively in his introduction to “The Gangsters Last Throne,” even including several pages of bible verses that speak of forgiveness.

Interestingly, although his poetry seethes with regret and mourning for past transgressions, he speaks of forgiveness as if it is his desire to give it, not receive it. “Forgiveness is the word I shall use,” he said to those gathered at his execution. “I hold no rancor, no revenge against anyone. ‘Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.’”