Tucked inside Galveston’s lively arts district on Postoffice Street, AOP Art on Postoffice Gallery (formerly The Shoppes on Postoffice) is home to a trio of Texas artists whose distinct styles create a compelling tapestry of expression.

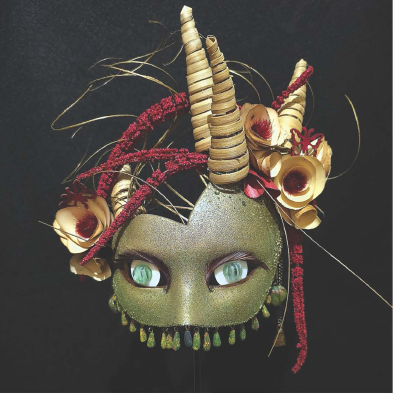

Basia Hawicz adds a whimsical and theatrical flair with her handmade masks and ornate Pisanki eggs, drawing on her background in theater and architecture. Her fantastical and cultural sculptures invite viewers to consider the many faces that color our world.

Patsy Lindamood’s graphite drawings capture a haunting realism. Her intricate renderings of old shrimp boats and weathered buildings blur the lines between photography and pencil, evoking a deep nostalgia for Gulf Coast heritage.

Across the gallery and working under M. Goodgame, Marshall Morgan gives discarded materials new life through abstract assemblages. His free form works challenge viewers to appreciate their raw beauty.

The work of these three artists helps transform AOP Gallery into a celebration of imagination and craft.

Basia Haszlakiewic

Known professionally as Basia Hawicz, this Houston artist transforms discarded treasures into ornate masks and egg art that obscures the difference between fantasy and folk tradition. Her studio is where discarded rhinestones, Barbie shoes, and forgotten trinkets are reborn as whimsical masks and dazzling egg sculptures.

A theater design and interior architecture veteran, Hawicz has found new creative freedom in an art form that blends personal history, cultural heritage, and the joy of storytelling. Her love for the classic forms - rooted in the grandeur of ancient Greek drama and the flamboyant pageantry of Italian Carnival - has never waned.

“Initially, I made masks for costume balls and masquerades, but later, I designed costumes for children’s theater while still working in architecture. I knew for a long time I’d return to this craft in earnest,” she said.

“Initially, I made masks for costume balls and masquerades, but later, I designed costumes for children’s theater while still working in architecture. I knew for a long time I’d return to this craft in earnest,” she said.

That return came after retirement, though not in the way Hawicz initially imagined. While cleaning her children’s rooms, she stumbled upon a treasure trove of Barbie doll accessories, bits of old jewelry, and assorted craft materials.

“I was inspired by a substantial collection of Barbie doll accessories, plus leftovers from years of crafts and costume making.”

Soon, friends began donating their own forgotten treasures like rhinestones, microbeads, and nail art supplies. Hawicz’s signature style was born using a fantastical blend of found objects, scaled for theatrical effect.

Her creations tell a story, an interplay between material and imagination. Some characters emerge fully formed, while others evolve from the materials at hand.

“Someone once suggested I do something ‘sharp,’ which led to the creation of ‘Steel Feathers.’ Another mask, ‘Diva,’ was inspired by someone glamorous and demure,” she said.

“But sometimes, personalities develop as I gather materials. A mask named ‘Amber Strata’ came to life just through working with its color palette.”

Her “Fantasy Pisanki” is an elaborate egg artform rooted in Slavic tradition that emerged more serendipitously.

“One year, during a Polish-style Easter brunch, I was decorating eggs and thought, why not add some leftover bling from my masks?”

What began as playful experimentation has since evolved into intricate, jewel-like creations, blending Old World folk art with a distinctly modern twist.

“These pieces are strongly influenced by architecture,” she said. “They’re engineered and structured.”

Whether it’s a mask or an egg, Hawicz thrives on the hunt for the perfect object to anchor each piece.

Whether it’s a mask or an egg, Hawicz thrives on the hunt for the perfect object to anchor each piece.

“It is so much fun finding a perfect centerpiece and creating a setting for it,” she said.

A favorite hunting ground is the Texas Art Asylum, a resale space where artists can score unusual and discarded items.

“You find some crazy things there. Friends still give me odds and ends, too - ironically, I probably bought much of it for my daughters years ago.”

While some of her masks were once meant for masquerade balls, they are primarily designed for display today.

“Very few people ever wear my masks, which is quite a relief,” Hawicz said. “It frees me to add more expression to the faces, like incorporating eyes, which changes everything.”

She navigates technical concerns like weight, durability, and safe adhesives for wearable masks.

Just like her detailed masks, her elaborate egg art demands similar care.

“I reinforce the shells from the inside with white glue, and I’m always testing adhesives. I recommend displaying them under a simple glass dome.”

As she looks to the future, Hawicz is contemplating new directions.

“I’m thinking about integrating masks into decorative picture frames,” she said. “That way, the frame becomes part of the art and creates a more practical way to display the piece.”

Despite the challenges, Hawicz finds deep satisfaction in her craft.

“It does get frustrating at times. Some compositions sit unfinished for months, waiting for the right element.”

When the right piece finally clicks into place, it’s magic and a reminder that the beauty of her work lies in the unexpected.

Marshall Morgan

In Galveston’s East End, where buried histories lie beneath the surface, artist Marshall Morgan, aka M. Goodgame, finds his muse. Morgan doesn't see trash among rusted bolts, chipped religious icons, and weathered glass bottles; he sees stories.

In Galveston’s East End, where buried histories lie beneath the surface, artist Marshall Morgan, aka M. Goodgame, finds his muse. Morgan doesn't see trash among rusted bolts, chipped religious icons, and weathered glass bottles; he sees stories.

“I wouldn’t call it a style so much as a way of seeing,” Morgan said. “I take discarded things and put them together in a way that makes you look twice.”

Morgan’s assemblage art reimagines forgotten objects into provocative, often humorous, narratives. Industrial debris, broken toys, and relics from Galveston’s layered past become the bones of his sculptures.

One of his signature works, “He Nails It,” features a figure of Jesus poised on a diving board above a silver bowl filled with blue paint. Saint medallions encircle the scene.

“It’s irreverent but also sincere,” he said. “That’s what I do. I assemble moments, not just objects.”

Morgan’s fascination with salvaged history began with a chance encounter.

“It started with a three-wheeled trike and a pile of curbside junk on the East End. I couldn’t leave it alone. I saw stories in it, these pieces of lives once lived.”

For Morgan, Galveston is an archaeological playground. After the 1900 Storm, much of the city was raised and filled, entombing everyday objects beneath layers of sediment.

“Galveston is built atop its own ruins,” he said. “The city was raised after 1900, burying whole streets, whole histories. When I dig, I’m not just looking for objects; I’m looking for what got left behind.”

He shares his digging rituals like a trade secret.

“There are tricks. If you sink a probe into the ground and it moves easily, there’s something below it. If it’s tight, it’s just dirt,” he said.

Privy sites and old dumping grounds, like the backlot of a hotel on Bath Street, have yielded treasures like pre-1900 glass, marbles, and the worn soles from children’s shoes.

“When you find something like that, it’s a moment of connection. It’s like shaking hands with history.”

Morgan’s studio is a cabinet of curiosities, populated with odd juxtapositions. Heads mounted on oil cans, weathered glass clustered inside rusted containers, religious emblems colliding with industrial artifacts, to name a few.

One such piece, named “We’re Screwed,” features a sideways Chevy emblem affixed to a towering cross with a briefcase-toting salesman standing nearby. A massive screw appears to torque into the work’s surface.

One such piece, named “We’re Screwed,” features a sideways Chevy emblem affixed to a towering cross with a briefcase-toting salesman standing nearby. A massive screw appears to torque into the work’s surface.

“It’s about what we worship. Money, brands, power [for example],” he said. “Some people get the humor, some don’t, but it makes them think either way.”

While humor threads through much of his work, some pieces lean toward the meditative.

He describes a favorite creation of an antique Asian porcelain man with a hat to the side, and his face is turned away. Next to him, a small bird perches on the rim of a matte turquoise-green ceramic cup, one of his wife Wendy’s first pieces.

“The scene sits on a piece of slate. It’s simple, but something about it feels sacred.”

Morgan thrives on viewers’ double-takes when confusion gives way to curiosity.

“That’s the best,” he said. “I put the pieces together, but what people see is theirs to decide.”

When he isn’t assembling found objects into layered compositions, Morgan tracks down vintage watches, another exercise in patience and storytelling.

“Finding them is a lot like digging. Tracking down something cool, something rare, something with a story.”

And when the studio grows quiet, Morgan often mows lawns for his elderly neighbors. “It’s meditative, and it keeps me moving. Plus, they like it.”

Ultimately, Morgan’s work is about honoring lives and histories half-buried and nearly forgotten.

“You learn to read the layers of the earth like a story,” he said. In Galveston, where the past is never too far below the surface, Morgan is one of the city’s most attentive readers.

Patsy Lindamood

The subtle beauty of weathered structures and working boats has long captivated artist

Patsy Lindamood.

A Huntsville, Texas-based artist, her graphite and watercolor pencil drawings have the kind of meticulous detail and atmospheric depth that can easily be mistaken for vintage black-and-white photographs.

Behind every stroke of her pencil is a story deeply rooted in history and geometry.

“Initially, I acquired a reputation as a wildlife artist,” Lindamood said. “Doing fieldwork to gather shorebird and predator references led me to marinas, where I had my first up-close experiences with workboats.”

There, among the rigging and worn hulls, Lindamood found herself hooked.

“Their imposing lines and shapes and all that rigging just resonated with me,” she said. “Geometry and trigonometry were my most favored math classes.”

That early fascination with math and structure carried over into her art. Boats like “The Green Hornet” and “Lady Nora” became her first “OG” workboat pieces, sparking a mission to seek out more vessels to draw.

“The more well-worn [the boats were], the better,” she said.

But it’s not just boats that catch her eye. Lindamood has a special affinity for historic architecture, particularly in Galveston.

But it’s not just boats that catch her eye. Lindamood has a special affinity for historic architecture, particularly in Galveston.

“One of my first architectural pieces was a rendition of the Star Drug Store on 23rd Street,” she said. “That building, its history, and that Coca-Cola sign have cast a spell over me that I can't seem to shake.”

Her award-winning piece, “Above the Old Star Drug Store,” was purchased by a collector who stayed in one of the lofts above the landmark.

“As an artist, that kind of connection is just mind-blowing.”

Lindamood’s work is driven by her connection to the details and the stories behind them. Her drawings of Galveston alleyways, with their layered bricks and patchwork history, have been exhibited in markets from Santa Fe to New York City.

“When I see three, four, or five brick patterns, I know those patterns represent changes and evolution. They represent different visions and expectations for the spaces within,” she said.

“Beyond those stories of remodels and rehabs, these texture variations are just visually stimulating.”

Despite her deep ties to Texas’ coastal imagery, Lindamood doesn’t live near the Gulf.

“I live and work in Huntsville,” she said. “But when staffing my booth at a festival, I’m frequently asked if I live somewhere coastal. It’s as if visitors assume I must live in a coastal town to create this kind of art.”

She finds that assumption flattering, a testament to the authenticity and atmosphere she infuses into each piece.

“Galveston is special because aside from its birds, it has a unique architectural and maritime history.”

Balancing a full-time role as CFO of a credit union with her demanding art practice, Lindamood’s days are carefully orchestrated.

“Most weeks, I probably spend 30 to 40 hours on art,” she said.

Mornings are often spent writing bios or preparing marketing materials before heading to work, while evenings and weekends are typically devoted to studio time.

“Pulling it off requires remaining healthy. I do indoor rowing five or six days a week. And I carefully manage my time.”

Lindamood sees parallels between her two careers.

“Subjects I most enjoy drawing are those with strong lines and shapes. Think geometry, think the golden ratio, and the Fibonacci sequence. Nature and architecture are both founded on mathematical principles. Financial analysis and accounting use mathematical systems, too.”

Her involvement with Galveston’s AOP Art on Postoffice Gallery has added another layer to her artistic practice.

Her involvement with Galveston’s AOP Art on Postoffice Gallery has added another layer to her artistic practice.

“Visual artists spend hours alone, so opportunities to gather and talk shop are welcomed,” she said. “Being part of a gallery with monthly ArtWalks provides strong motivation to continue producing new art.”

So, how does she know when a piece is finished? For Lindamood, it’s more emotional than technical.

“Are the right details there? The ones that evoke those emotions or recollections?” she said. “Details matter in my work, but not the replication of every detail in my reference.”

For Lindamood, every line and shadow is a tribute to the histories embedded in weathered boats, crumbling bricks, and bird-laden shorelines. While she may live inland, her heart and her art, are anchored on the Texas coast.