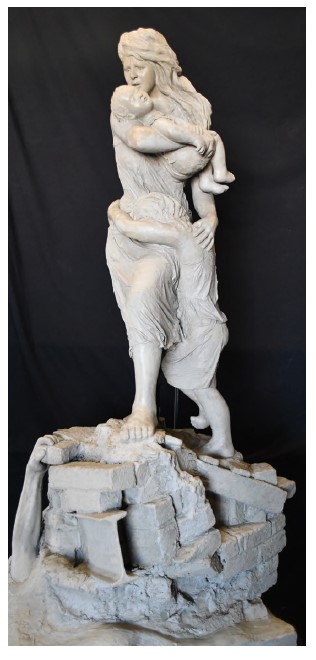

When Galveston artist Doug McLean arrived at the Omega Bronze foundry in Smithville, he knew he was finally about to see his vision become a reality. After months of sculpting “Hope,” an interpretation of a plaster sculpture by Pompeo Coppini honoring the victims and survivors of the 1900 Storm, community fundraising efforts provided the means to translate his work into bronze.

When Galveston artist Doug McLean arrived at the Omega Bronze foundry in Smithville, he knew he was finally about to see his vision become a reality. After months of sculpting “Hope,” an interpretation of a plaster sculpture by Pompeo Coppini honoring the victims and survivors of the 1900 Storm, community fundraising efforts provided the means to translate his work into bronze.

“It feels terrific to be here,” McLean shares. “I’ve waited a long time for this and questioned whether it was ever going to happen—whether it would always be the original clay sculpture sitting in my studio.”

The sculptor chose the small-town foundry owned by Stephen Zabel not only because of their impressive reputation, but also because he felt it was important the artwork be completed in Texas.

However, the people who work at the foundry are skilled artisans in their own right. Using a process based on the “lost wax” technique that has been practiced for 5,000 years, they transformed the clay sculpture into a bronze statue through multiple, intricate steps.

A crew from Omega arrived at McLean’s studio a few weeks earlier to prepare “Hope” for the molding process. Cutting the clay sculpture apart was one of the first procedures.

Any parts of the figures that stood away from the main section, including the woman’s head, her baby, and an arm reaching up from the rubble, had to be carefully cut away. A cast made with gaps and ledges would make it impossible to pull the finished mold away from the figure.

McLean admits it was a little unnerving to watch his work being cut into pieces, but he understood it was necessary. After those pieces were removed, Zabel and one of his workers used playing cards as shims, inserting the edges into the remaining clay in lines to mark the next sections to be cut.

Once the cards defined all the shim lines, workers coated the figure with silicone rubber and left it to harden overnight. “It took them a solid 15 hours just to do that,” McLean shares.

The following morning, they applied a fibrous plaster shell to the entire form. Once the shell dried, the sculpture was separated into sections along the dividing lines marked by the cards and transported to the foundry in Smithville. “Ultimately the mold weighed between 500-600 pounds with the shell,” McLean explains.

“All of this will be welded back together once it’s in bronze,” explained Zabel at the time. “We usually cast about 24x24-inch sections, or we’d need more specialized equipment to move it around. ‘Hope’ was cut into about 10 different pieces and made into 10 different molds. Once the pieces are welded back together, you’ll never know it was ever cut apart.”

When pieces of “Hope” arrived at Omega, the original clay was removed from each portion, revealing a negative impression in the rubber coating. These were taken to the Wax Room where ochre-colored wax splashes on the wall mark the hours spent on previous commissions. There, the rubber impressions were carefully coated with 3/16” of melted wax, and allowed to dry before reassembling the pieces of the mold.

An investment material was then poured inside the molds to support the wax forms. After that dried, the external rubber structure was removed revealing a wax version of the original clay sculpture.

“That’s the stage where the wax appears just like the statue,” says Zabel. “We take those wax pieces and clean them up, removing air bubbles and smoothing lines where necessary to make sure the artists’ vision is intact.”

Each detailed wax creation then made its way to the Shell Room. The room is deafeningly loud due to industrial mixers and fans, and rows of shelves are lined with portions of works in progress.

The wax pieces were dipped into a slurry that coated the exterior then left to harden on shelves, a process repeated up to 15 times, according to Zabel. Once the outer shells were applied, some pieces were fairly recognizable as “plumper” versions of the original art, and other shapes kept their identity a mystery.

After the shells were complete, the pieces were placed in a kiln to melt away the wax inside, which is where the “lost wax” technique got its name. The space left between the outer shell and internal investment is where the bronze was poured to replicate the artwork.

Although each step of the process is painstaking and fascinating, the pouring of molten bronze into the molds was the most spectacular to witness. McLean and his guests walked through the foundry past a recently completed project of the crew: a towering bronze statue of a woman holding a lantern in her extended arm. On the back porch, two men wearing silver fireproof coats, shoe covers, gloves, and face shields prepared for the pour.

A few shell molds at a time were placed in a kiln to be heated, and then nestled into sand-filled troughs beside a small wooden wall that bore the burn marks from previously splashed materials. A funnel was attached to each piece to direct the molten bronze.

Zabel and one of his workers lifted a brightly glowing pot of molten bronze called a crucible out of the furnace with a wench. They carefully grasped the pot with long-armed clamps and skillfully lowered it, tipping it slightly to fill each mold.

Molten bronze radiated an orange light out of the funnels leading into the molds, as small occasional splashes jumped from the pot and hit the concrete below. The process that took days to prepare was over fairly quickly, but was repeated several times to utilize all of the necessary molds.

After the bronze cooled, the molds were devested which entails breaking away the ceramic shells with hammers to reveal the bronze pieces inside. Onlookers were intrigued with that process too, since it was a bit like a treasure hunt to identify different parts of the statue.

Exclamations of “Oh, that’s the baby!” “Look an arm!” and “I see a face!” revealed the enthusiasm of the group.

Once the individual bronze sections were sandblasted to remove all traces of their former shells, they were welded together. A patina finish was painted on the statue as a finishing touch, and “Hope” was ready to return to the island.

“Hope” will be installed later this year for the public to enjoy 121 years after the hurricane that inspired it. The statue will be located in Galveston's new city park at 823 25th Street that is currently under development. The park is being built where the now demolished annex building was located behind city hall.