At 5 am on September 18, 2022, Galveston photographer Daphne Watkins hopped out of bed, grabbed some coffee and headed out, intent on capturing the beauty of the island on which she lives.

“Of course, like everybody else who lives on this beautiful island, I love to take sunrise and sunset pictures. I’m more of a morning person, so I mostly get the beautiful sunrises, but I’ve slowly started taking pictures of other things that interest me, like dragonflies, native flowers and butterflies.”

Her passion for communing with nature both buoys her spirts and regenerates her energy after long hours as a pediatric nurse at The University of Texas Medical Branch, where she has worked as a registered nurse for 25 years.

“I’m like an excited little girl going out with my camera for the first time, every time. Looking through the camera lens has opened up a whole new world for me,” said Watkins, who began her love of photography as a teenager but started in earnest five years ago.

“I’m passionate about it and learn something new every day about photography.”

On that particular day, she focused on documenting some of the estimated two billion birds that migrate through Texas from August 15 through November 30.

Galveston is an important habitat for “snow” birds that spend winters on the island, including large, long-legged shorebirds like the marbled godwit and the belted kingfisher, stocky, large-headed birds with a shaggy crest on the top and back of the head and a straight, thick, pointed bill that produces a wild rattling call as it flies.

The area is also winter home to raptors like red-tailed hawks, one of the largest birds you'll see in North America, and osprey, which is unique among hawks because of its reversible outer toe that allows them to grasp with two toes in front and two behind.

“It’s been a lot of fun learning about all the different birds here on the island, as well as the birds that pass through here during migration: beautiful birds like the spoonbill; the black-necked stilt, which is such a cute bird; the elegant white egret; and the comical reddish egret, who dances all around while hunting his prey,” she said.

“I’m living in paradise here on the island. When I’m not working, I’m outside a lot, so it was only natural to be drawn to nature and taking pictures of wildlife.”

When she returned home September 18, she went through her photos, and stopped at one image that captured her attention.

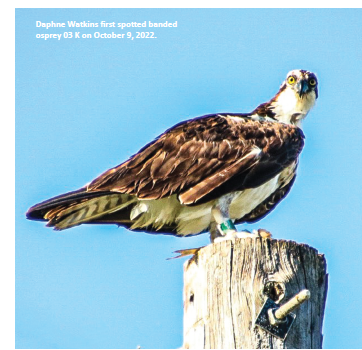

“I noticed that in one of the pictures of the osprey there was a band on his leg. So, I zoomed in and saw there were actually two bands—there was a red band on his left leg and a metal band on his right leg.”

She realized a banded bird must hold some importance to researchers and conservationists, so she headed to the United States Geological Survey’s Bird Banding Laboratory website to find out how to report her find.

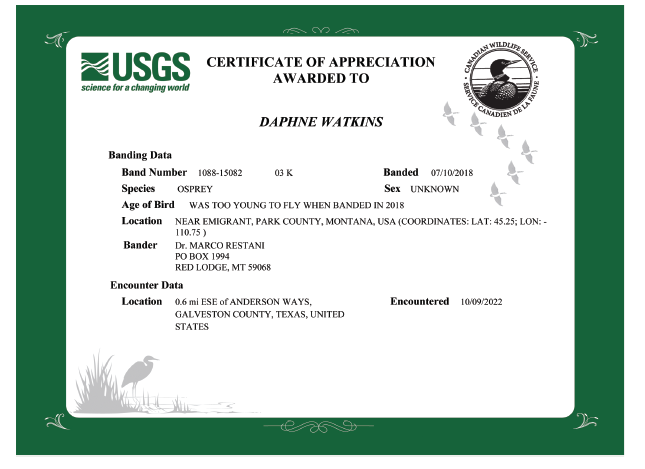

“The USGS’s banded bird program gathers data for developing effective science, management and conservation practices. I was directed to fill out the information about the bird and send it in. … The very next day, I was sent a ‘certificate of appreciation’ via email for reporting the banded osprey,” she said.

“The USGS’s banded bird program gathers data for developing effective science, management and conservation practices. I was directed to fill out the information about the bird and send it in. … The very next day, I was sent a ‘certificate of appreciation’ via email for reporting the banded osprey,” she said.

“It also had other information about when he was banded, in 2017, which makes him about five years old. On the certificate it lists his age at banding as ‘too young to fly.’ He was banded at the Boise State University in Boise, Idaho. I was so excited, my bird was all the way from Boise, Idaho.”

Watkins was flying high. On October 9, she returned to the west end of the island to capture images of more ospreys, one of which she hoped would be her “Boise bird.”

“I couldn’t really tell until I got home and went through my pictures to see if there were any bands on the birds,” she said.

“Well, there was no Idaho osprey, but I did get myself another banded osprey: This one only had one band, and it was on the right leg. I got online and reported him, too.”

A week later, she heard from Marco Restani, Professor Emeritus of Wildlife Ecology at St. Cloud State University. He wrote:

Greetings Daphne,

Greetings Daphne,

I recently received word from the USGS Bird Banding Lab that you observed an osprey I had banded in Montana. I banded 03/K (green on the left leg, silver band on the right leg) as a nestling on 10 July 2018 near Emigrant.

The bird was about 35 days old at banding and had two siblings. If you use google earth, you can see the nest platform at 45.311514, -110.817594.

I collaborate with 40+ volunteers from the Yellowstone Valley Audubon Society and five power companies. The volunteers monitor about 100 osprey nests along the Yellowstone River from Gardiner to Miles City.

The vast majority of the nests exist on pole nest platforms erected by power companies to get the birds away from live wires. The project began in 2009 and since 2012 I have banded 780 nestlings.

We've had banded ospreys from our project winter along the Atlantic Coast in South Carolina and Florida, and across the entire Gulf Coast from Florida through to the Yucatan. We've also had a few winter as far south as Costa Rica and as far east as Puerto Rico.

Quite a few have ended up wintering near Galveston, and I appreciate your efforts in reading the green band code….

“I was beyond excited about this. What are the chances that I would see two banded birds within about a month’s time? It’s pretty amazing I can be a part of the program just by identifying a banded bird,” Watkins said.

“The program itself has banded millions of birds. What are the chances I would get a picture of one, much less a picture of two of the banded birds? It has been pretty exciting for me to see that doing something I love can have an impact on tracking birds and bird conservation.”

Now, when she hops out of her midtown Galveston nest, camera and coffee in hand, she feels even more bonded to the birds she’s spent countless hours communing with on the island.

“Ospreys, oh, man, I didn’t even know what they were until I started shooting. …Reading and learning about these birds has been a lot of the fun for me. I identified a crested caracara out on the east end of Galveston. Every time I went out shooting, I saw him again and again up in the same tree in the same place for well over a month. Then, one day, he was just gone, and I figured he had just moved on. Come to find out he had moved, but not far—just right across the street from where he had been. He had moved to a bigger place, a dead palm tree, because he now had a family—a wife and a baby—and he needed a bigger place.”

For more information about the United States Geological Survey’s Bird Banding Laboratory, visit usgs.gov/labs/bird-banding-laboratory.

For more information about The Osprey Project, visit bigskyjournal.com/the-osprey-project.

Galveston Monthly has created a database of images to assist in tracking banded birds that have been seen in our area. Anyone who has had the opportunity to photograph any type of banded bird in our area please email the images to john@galvestonmonthly.com.