Galveston is often heralded for its survivor spirit. Yet even this lofty (and well-deserved) label, given for the community’s ability to overcome seemingly insurmountable forces of nature, underplays the fact that time after time, this island city has done far more than merely survive. Even the mainstream narrative of island history often reaches its dramatic climax on September 8, 1900, lazily crediting The Great Storm with a consequent economic devastation that instantly transformed Broadway mansions into museums.

The story of Galveston’s dramatic comeback from the 1900 Storm and its ensuing domination of nationwide commerce and pop culture during the first half of the 20th Century has been largely forgotten, undoubtedly a result of losing much of the era’s emblematic architecture. But it will never entirely be erased, at least not as long as the United Stated National Bank Building stands at 2201 Market.

Polish immigrant Harris Kempner moved to Galveston in 1870. An innately adept economist and Civil War veteran, Harris founded a local wholesale grocery and import company with a man named Marx Marx that focused on basic but ubiquitous and profitable goods like salt and coffee.

They also capitalized on Galveston’s massive cotton compress and export industry by supplying packing materials for its preparation and shipment. Simultaneously, Harris invested heavily outside his business including large land acquisitions, and later parlayed a stroke of misfortune into his most enduring endeavor.

Much of Kempner’s financial maneuvering was being handled by Island City Savings Bank, founded in 1874. Instead of taking his business elsewhere when the bank lost several of his significant investments in 1885, Harris made a characteristically bold play and became president of the bank’s reorganization committee.

The following year, he dissolved his partnership with Marx and began working to improve the transportation of cotton while expanding his bank holdings. Harris served as president of the Texas Land and Loan Company for several years and became both stockholder and director at various times for a multitude of banks in cities across Texas including Giddings, Cameron, Mexia, Ballinger, Athens, Groesbeck, Marble Falls, Gatesville, Velasco, and Hamilton.

After Harris’s death in 1894, his immense wealth and diverse assets were ceded to the dutiful watch of his eldest son, Isaac H. “Ike” Kempner. At the age of 21, Isaac was forced to drop out of Washington and Lee University in Virginia and return to Galveston to take over his father’s vast and rapidly expanding empire.

Over the next several decades, Ike Kempner not only exponentially increased his family’s holdings even further with the founding of Imperial Sugar Company and the subsequent town of Sugar Land, he became a crucial proponent for the continued economic and civic advancement of Galveston and a dynamic catalyst behind its astonishing rebound from the deadliest and most destructive storm in U.S. history.

The tragedies of the 1900 Storm were not lost on Isaac Kempner, but neither were the opportunities posed by the upheaval. The city government was already defunct and bankrupt even before the storm, and so Kempner set out to rewrite the city charter and reorganize the municipal government into a commission form of government that arranged the governing body like a board of directors.

He coined the phrase, “The Spirit of Galveston” to encourage storm survivors disheartened by street corners that were now crematoriums and a 20-foot high wall of debris that encircled the northern half of the city, made of everything that previously stood on the southern half.

Ike rallied fellow business owners and local import/exporters, and almost as a testament to his entrepreneurial and organizational talents, Galveston exported its largest tonnage of cotton ever recorded less than two months after the storm. Ike went on to champion the restoration of the Port of Galveston with the most technologically advanced wharves in the world, and he helped assemble the Board of Engineers who designed the seawall and grade-raising while contributing financially to both projects.

As a result of Isaac Kempner’s tenacity and vision, Galveston’s commercial economy continued to grow, and the port continued to break records. Even after the Houston Ship Channel opened in 1914, Galveston remained a leading cotton exporter for decades, although starting in the 1920s, the main source of prosperity and wealth in Galveston was henceforth the result of the Maceo family and their transformation of Galveston into a premiere resort destination.

On August 7, 1902, Isaac solidified the Kempner family interests initially pursued by his father when he purchased the old Island City Savings Bank—the very bank that marked Harris’s entrance into the industry. At the time of acquisition, the institution had a capital stock of $100,000 and an equal surplus, while deposits hovered around $400,000.

On May 22, 1903, the name of the bank was changed to Texas Bank and Trust Co. with a capital stock and surplus each at $200,000. Eighteen months later, deposits had ballooned to over $2 million.

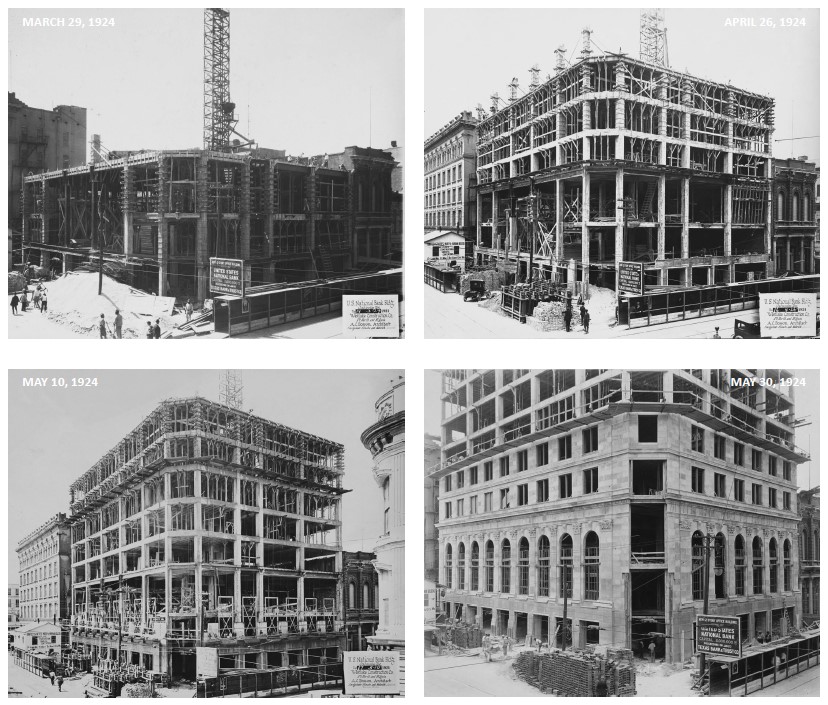

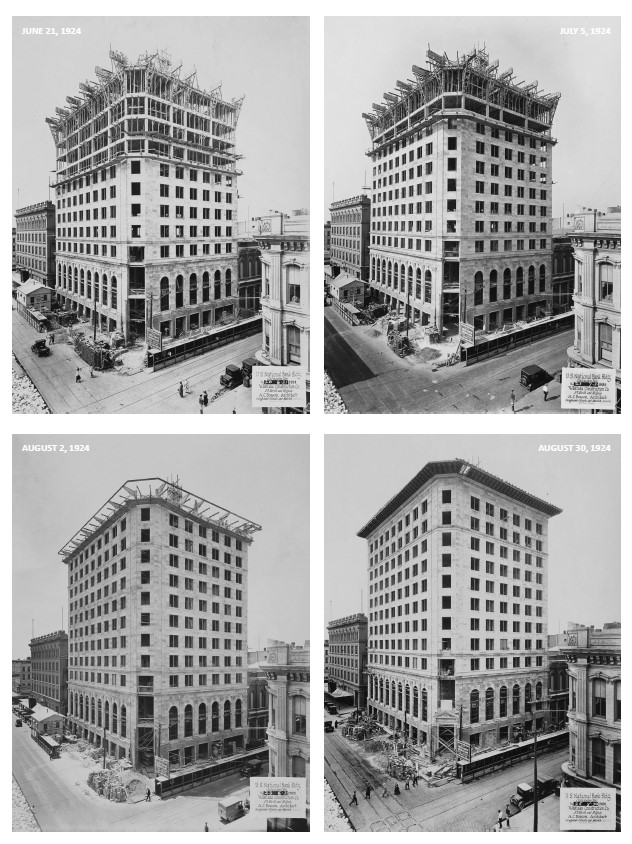

In January of 1923, Ike Kempner officially announced that construction would commence on their new banking tower on the southwest corner of Market and 22nd Street. Exactly one year later, on January 1, 1924, the Texas Bank and Trust Company became the United States National Bank with a capital stock of $1 million and a surplus of $600,000.

By the end of that same year, deposits had reached a staggering $15 million ($225 million today). Kempner’s Galveston bank was the last one chartered using the USNB moniker. In 1926, Congress passed legislation banning banks from using the words “United States,” “Federal,” or “Reserve” in their titles for obvious reasons.

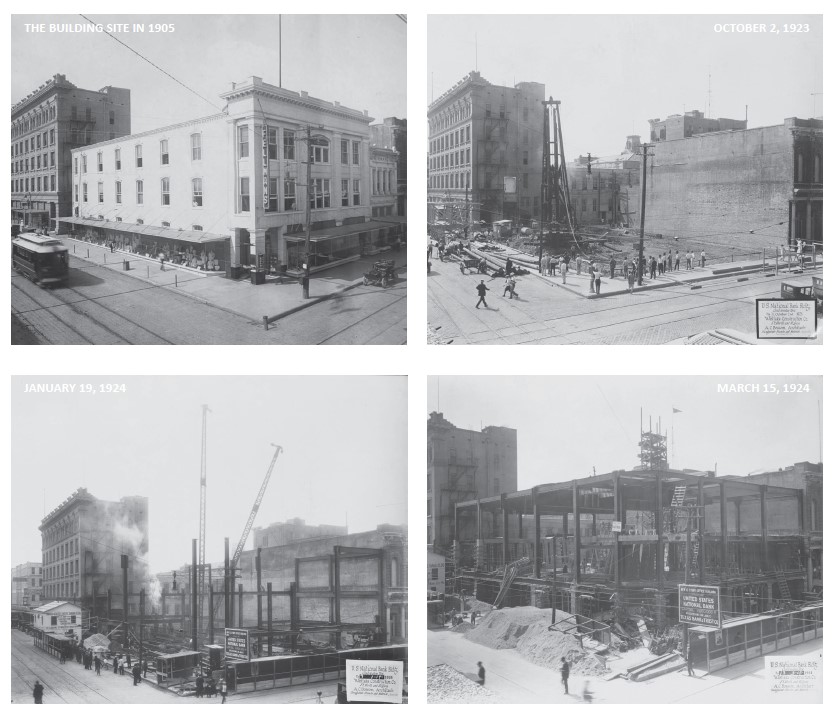

Plans for a new Kempner bank building had been discussed since 1921 when the lot was initially purchased by Texas Bank. The lot held a three-story structure leased to a company called Hammersmith’s, and the bank cordially allowed the tenants to retain occupancy until the expiration of their lease. It was then revealed that the structure would be demolished to make way for the tallest building on the island, to be commenced in July 1923 and completed and occupied by the following summer.

Kempner hired famed bank architect Alfred C. Bossom of New York who had been awarded the prize of best building constructed in New York City in 1920 for his design of the Seaboard National Bank. A native of London, Bossom moved his architectural practice to the United States in 1903 where his studied and methodical intellect was drawn to the mathematical marvel of skyscraper construction, at the time a booming industry in America.

By 1918, his firm on Fifth Avenue was overseeing numerous commissions all over the country, although the bulk of the work was coming from the east coast and oddly enough, Texas. Prior to the Galveston USNB, Bossom had already garnered acclaim in the state from his construction of the American Exchange National Bank (1918) and the Magnolia Building (1922), both in Dallas.

Studious and methodical, Bossom was both an architect and an engineer known for conducting extensive interviews and learning the processes of each bank before beginning his design. His major contribution to this era of architecture was implementing existing technologies with amplified efficiency, and thusly did he design the interior of his buildings to maximize the efficiency of the entity that would be inhabiting it.

Originally, the USNB building was planned as an eleven-story tower, however, in keeping with Galveston’s thriving downtown and urban cityscape, it was ultimately decided to place the bank itself on the second floor (comprised of both the 2nd and 3rd stories), which would allow for the placement of various retail spaces on the street level.

Structurally, these first three floors were the base of the building, framed with steel beams and wrapped in polished granite. The ground floor retail spaces featured floor to ceiling, brightly lit display windows to give the building an attractive appearance even during the evening hours, while 19-foot-high arched windows lined the exterior of the combination 2nd and 3rd floor bank space.

Rising above the base, the remaining nine stories were fashioned from reinforced concrete and laid with an exterior of Indiana limestone. The offices contained on floors 4-10, laid out in various sizes and formations, were situated so that each was an “outside” room with no fewer than two windows for ventilation and natural light. The 11th floor was to be the headquarters of the firm of Harris Kempner, Isaac Kempner presiding, while the 12th was outfitted with a cotton sampling room and its own elevator so that the fluff from the cotton samples would not spread throughout the rest of the building.

Bossom crowned the large structure with a copper cornice that juts out eight feet from the perimeter of the roofline. He deemed the building’s design “Italian Renaissance, but without elaborate detail on account of the great height of the building.” This modest but imposing exterior design was an elegant contrast to the stunning and ornate interior.

Still beautifully preserved today, a gorgeous, Spanish-style marble staircase embossed with a gold railing led from the first floor to the bank. Once through the bronze doors, the officers’ quarters were located to the right, including a large office for the president. Opposite the officers was a customer lounge, and at the far end of the room were the teller cages.

In between and visible from every point in the second floor was the main vault that contained coupon booths and safety deposit boxes. The entire bank was outfitted with the most up-to-date banking technology, including a soundproof room where the accounting machines were placed so as not to disturb customers.

Alfred Bossom commissioned for the interior décor Alfred C. Ulrich, Inc., decorators and general contractors, as well as Robert Lehman, a world-famous interior designer, both from New York. Both Lehman and Ulrich were on site long after Bossom’s work was completed and remained even after the building’s opening to finalize the finishing touches.

Lehman referred to the grand lobby and banking room as his “studio,” appropriate considering that he hand-carved the reliefs and sculptures in the walls, ceiling, and flooring of the banking offices. The lobby was painted a sky-blue and embellished with a ceiling plan adopted from old Italian cathedral designs, painted in a neutral sepia tone.

The carving of the ceiling stones alone took Lehman more than a month to complete. Three massive, antique bronze chandeliers completed the effect.

Room after room, the banking center produced one aesthetic marvel after another. The directors’ room was treated with gold effects and paneled with antique brown oak and topped with a rainbow-colored ceiling.

The conference room featured pastel brown walls that glowed with the light of two silver chandeliers, the hallway was lined with finished walnut, and the president’s office featured a huge marble fireplace and a private hallway guarded by iron doors.

Due to unavoidable circumstances and minor setbacks, the construction of the United States National Bank Building took nearly a year longer than was originally planned. In early 1925, the opening reception was finally scheduled for Saturday, March 21, 1925 at 4pm. Private invitations were sent out, and a general invitation to the public was released.

On March 19, the Galveston Tribune released a special edition that included a 24-page section dedicated exclusively to Galveston’s newest and most daring architectural feat to date. Within the section, readers were encouraged, “Mail today’s copy to an out-of-town friend and help spread the gospel of a Greater Galveston.”