Much like the cities that celebrate it, Mardi

Gras is richly unique. While many other holidays have been hijacked by

marketing firms and diluted by societal evolution, Carnival remains authentic.

While most traditional festivities are more or less mandatory via the

declaration of them as nationwide observances, Mardi Gras is only celebrated

regionally and has grown organically, with a history that parallels the early

growth of certain American cities that were heavily influenced by European

cultures.

This is precisely how and why Galveston adopted the Mardi Gras tradition in 1867, and

why it blossomed into what was once one of the most outlandish and elaborate

celebrations in the nation, rivaled only by the Carnival capital itself, New Orleans.

Perhaps the holiday’s uniqueness is what

resonated with Island icon George P. Mitchell when he sought to revive it in

the mid-1980s, and assuredly the direct ties of Mardi Gras to the cultural

fabric of Galveston did not escape him, as the city was forever shaped by the

array of global influences during its reign as a prosperous international port

of commerce and immigration in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries.

Amid the throes of World War II, economic and

supply issues forced Galveston to halt nearly 75 years of Mardi Gras tradition

in 1941, and the celebrations were forced into the private homes of the city’s

elite. The revelry remained isolated from the public until 1985 when Mitchell

singlehandedly gifted Galveston

with a triumphant return of Mardi Gras concurrent with the grand opening of his

new Tremont House hotel on Mechanic

Street.

That year he was named King of the Krewe of

Momus, and led the parade to the grand opening of the Mardi Gras Museum that

coincided with an art opening and appropriately included a book signing of The Gods of Greece by Arianna

Huffington, who would go on to start the Huffington

Post. Later, Mitchell sought to further immortalize

Galveston’s Carnival legacy through the Mardi Gras

Museum on the Strand. At the time, Mardi Gras

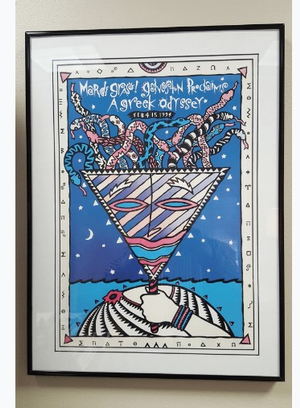

had a different theme every year in the tradition of the early Galveston celebrations. In 1994 the theme was

“Greece,” and Mr. Mitchell

had executed his usual dedication to the theme with a thorough decorating of

the Strand all the way down to Grecian street

signs and lamps.

Located on the third floor of Old Galveston Square on the Strand

between 22nd and 23rd Streets, admission to the Mardi

Gras Museum was only $1 and inside was a thoughtful and splendidly sentimental

monument to the beloved holiday. It brought all of the spectacle and wonder

down from the balconies and off of the mammoth parade floats and presented it

within arm’s reach; it was a glittering and vibrant tribute to all of the

intricate details that brought Mardi Gras to life each year.

Designed by the Eubanks Architecture Group,

the perimeters of the museum were outfitted with custom stained glass and a

brief history of Galveston Mardi Gras inscribed on the wall. Joseph Rozier, who

was then a recent college graduate employed by the Eubanks firm, produced

design drawings for the layout of the museum and continued to assist with

creating exhibits after it opened. He explains that several permanent displays flanked

a large, central gallery that hosted revolving exhibits, the most dramatic of

which was an enormous hanger fixed to the ceiling that allowed the museum to

interchange many examples of the magnificent, 12-foot long capes worn by former

queens and duchesses.

The permanent exhibits included donated items

from several Galveston Krewes. They featured early 20th century

costumes and various collections of historic memorabilia, like the custom

doubloons that were created by each Krewe every year. But garnering the most

attention were the three-dimensional models of the arches that were

commissioned by Mitchell to adorn the city streets in 1986. Seven world-famous

architects were asked to each design a “fantasy arch” for a Galveston intersection, a modern-day take on

the decorative arches that were erected for the 19th century

celebrations.

The permanent exhibits included donated items

from several Galveston Krewes. They featured early 20th century

costumes and various collections of historic memorabilia, like the custom

doubloons that were created by each Krewe every year. But garnering the most

attention were the three-dimensional models of the arches that were

commissioned by Mitchell to adorn the city streets in 1986. Seven world-famous

architects were asked to each design a “fantasy arch” for a Galveston intersection, a modern-day take on

the decorative arches that were erected for the 19th century

celebrations.

“The arches were built to be temporary,” says

Rozier, but the Pelli arch at 21st and Mechanic, lit by a series of

colored bulbs in a horizontal pattern, was kept up for six months. Gray’s arch

on the Strand also hung on for a significant

amount of time, and the Powell arch at 24th and Mechanic was rebuilt

and reinforced and remains to this day.

The project was distinguished by a 1987

exhibit at the Cooper-Hewitt

Museum, the national

museum of the Smithsonian Institution. “Arches of Galveston” included architectural renderings,

photographs, and models of each of the seven arches.

Unfortunately, the 3rd floor

location of the Mardi Gras Museum would prove a disadvantage. “Even though we

had an elevator and an escalator at the time, we simply didn’t get enough foot

traffic,” explains Rozier. “It was a labor issue, predominantly,” he continues,

“it required a full-time employee to staff the cash register to take admission

and sell merchandise [from the gift shop].” In 1996 the space was abandoned and

a satellite museum was opened across from the Tremont House, a location that

provided a comprehensive solution.

Unfortunately, the 3rd floor

location of the Mardi Gras Museum would prove a disadvantage. “Even though we

had an elevator and an escalator at the time, we simply didn’t get enough foot

traffic,” explains Rozier. “It was a labor issue, predominantly,” he continues,

“it required a full-time employee to staff the cash register to take admission

and sell merchandise [from the gift shop].” In 1996 the space was abandoned and

a satellite museum was opened across from the Tremont House, a location that

provided a comprehensive solution.

A local bookstore named Midsummer Night Books

occupied the storefront space of a building owned by Mitchell Historic

Properties at 2309 Mechanic. The owner agreed to play host to the museum, which

would be moved to a small annex next door at 2311. A thick concrete wall

separated the two addresses, but a portion of it was dismantled to create a

connecting passageway.

The gift shop was eliminated and the museum

was free and open to the public during the bookshop’s normal operating hours,

which removed the need for staff. Most importantly, foot traffic from the bookstore

and the hotel provided a much-desired visibility for the fascinating

collection.

“We moved the nicer things down to the

smaller annex, and gave all of the donated items back to the Krewes,” Rozier

recalls. A local artist named Cara Moore was hired to paint the floor with a

faux stone finish embellished with symbols of Mardi Gras, and a massive,

antique wooden display case featured a 1930s costume complete with headdress,

cape, and a stunning silver dress studded with thousands of sequins.

The Mardi Gras Museum remained a fixture of

downtown until Hurricane Ike in 2008, when a fast-rising storm surge prevented

the rescue of the museum’s already minimal contents. After the storm, neither

the bookstore nor the museum returned.

The Mardi Gras Museum remained a fixture of

downtown until Hurricane Ike in 2008, when a fast-rising storm surge prevented

the rescue of the museum’s already minimal contents. After the storm, neither

the bookstore nor the museum returned.

Today, the former location of Midsummer Night

Books and George’s museum is still owned by Mitchell Historic Properties and

currently houses one of Galveston’s

most dynamic art galleries, Arts on Mechanic.

Tour the Traces of

Galveston’s Mardi Gras Museum

Perhaps as a tongue-in-cheek

tribute to the Lenten season, the Mardi Gras Museum left behind several Easter

eggs when it closed. Some of them are (much) more obvious than others, but they

all blend in seamlessly with Galveston’s

Carnival identity.

Powell Arch at 24th

and Mechanic

Powell Arch at 24th

and Mechanic

On the east side of the

intersection of 24th Street and Mechanic, the Powell arch turned 30

last year and still beams brightly every night as a constant reminder of

Galveston’s Mardi Gras heritage.

Floor & Passageway at

Arts on Mechanic

Step inside the local art

gallery at 2309 Mechanic and look down. Much of the floor painted by Galveston artist Cara

Moore for the Mardi Gras Museum still remains. The annex and the wide

passageway created to connect it to the bookstore now gives an added dimension

to the storefront space.

Antique Display Case at Arts

on Mechanic

Antique Display Case at Arts

on Mechanic

In the annex of Arts on

Mechanic where the museum was located, the large, antique display case used for

the luminescent silver costume survived Ike and has stayed in place through

several businesses.

Light Fixture at Davidson

Ballroom

Inside Davidson Ballroom, the

Tremont House’s private party venue located across the street from the hotel,

attendees often use a beautiful stained glass light fixture as their backdrop

for photographs during special events. The fixture was originally incorporated

into a display at the first museum location on the Strand.

Stained Glass at Old Galveston Square

Over the entrance to the

original museum space on the third floor of Old Galveston

Square on the Strand, a stained glass window

with the image of a jester still remains to welcome visitors.