Gumbo is one of the most

controversial topics of culinary discussion. Right down to the very meaning of

the word, opposing ideologies maintain what is (or what should be) considered

the right way to make gumbo. The dish, rooted in Louisiana

culture, is reflective of America

itself. What may seem like a straightforward recipe becomes a full-on

representation of this country’s identity—a delicious melting pot of cultures

stewed into one great dish.

Some believe gumbo to be

named after the West African word for okra, ki ngombo, which

supports the school of thought that gumbo is only to be made with okra. Others

believe it to be named after the Choctaw word kombo which means

“sassafras leaf,” known to most southerners as gumbo filé (pronounced fee-lay). This creates a

foundation for those who believe gumbo should only be made with gumbo filé.

What we do know is that these ingredients

were brought to the kitchen, recipes were shared, and gumbo made its debut in

American culture as early as the 17th century. It was a staple dish

prepared in Louisiana

that crossed class and cultural barriers.

ROUX

ROUX

The base of this dish is the French

preparation called roux (pronounced roo), also known as the one thing on

which all gumbo connoisseurs will agree. This is a simple yet complex base that

gives the dish its most prominent flavor.

Simple because it is only two ingredients - flour

and fat. Complex both in flavor and its delicate nature which demands the

cook’s full attention while preparing it - mere seconds can make or break it.

Even the most seasoned chef can burn a roux.

To begin a roux, heat up the choice fat (cooking

oil, olive oil, butter, lard) on a medium heat until it glistens. Sift in

all-purpose flour and begin to whisk evenly into the fat. As you stir, the

color will develop from white to cream, from tan to peanut butter, and then you

get to the gumbo range- oak to cocoa. One thing to remember- don’t compromise

the dish with a burned roux, discard and start over.

The roux acts as a thickener, although it is

not the primary thickener in gumbo. Typically, a darker roux will give more

complex flavor to the dish, but the more the flour is broken down, the less

productive it is as a thickener.

OKRA VS. GUMBO FILÉ

OKRA VS. GUMBO FILÉ

Some of the more divisive opinions behind

gumbo preparation depend upon the style of Louisiana cuisine on which it is based.

Okra, with its West African origins, came to America

most likely during the slave trade and became quickly rooted in the New Orleans cuisine. It

was used as a thickener in dishes and in other as a main ingredient. Often,

okra-based gumbos will have tomato added, as these two items were often paired

together.

When using okra in gumbo, it is equally as

important to cook it down as it is to cook down the roux. Okra is a

mucilaginous plant, which means it creates a liquid binder when cooked.

However, when cooked long enough, the sticky nature of the fluid in okra can be

cooked off and turned into a paste.

This is what they mean when they say

okra-based. Not that you will ‘see’ okra in the gumbo, but that it is an

integral part in making the base of the dish.

The solitary use of gumbo filé was more commonly seen in Cajun dishes,

which was heavily influenced by Native American cuisine. Gumbo filé adds an earthiness to the dish and acts

as a thickener similar to okra but not as powerful.

The solitary use of gumbo filé was more commonly seen in Cajun dishes,

which was heavily influenced by Native American cuisine. Gumbo filé adds an earthiness to the dish and acts

as a thickener similar to okra but not as powerful.

Gumbo that uses only filé and no okra will have a thinner base

liquid. This is more common in meat gumbos, like chicken and sausage, or duck

and sausage.

Historically, gumbo filé was used as a substitute binder when okra

was not in season, because it was easier to dry, grind, and store gumbo file

than okra pods. Both items can be found at the grocery store these days,

although industry standards have allowed gumbo filé to be “cut” with sage as it can become

pricey per pound. (100% pure gumbo filé retails anywhere from $15-20/lb. Ground

sage is anywhere from $6-9/lb.) Be sure to read the label when purchasing gumbo

filé, or

ask your local spice merchant if their filé is pure.

CAJUN VS. CREOLE

This is where you begin to see the players

take sides. Louisiana has some of the greatest

food, however gumbo from Lafayette is

tremendously different than New

Orleans. This is because there are two main styles of

cooking gumbo - Cajun vs. Creole.

Typically, a Cajun gumbo is one thickened

with a dark roux and filé. This is a thinner style of gumbo and more prominent in the Galveston food scene.

Whereas a Creole gumbo is made with a dark roux but is thickened with Okra and

has the presence of tomato.

Creole gumbo is typically be found in New Orleans while Cajun

Gumbo is more likely to appear West of Bayou Lafourche. New Orleans famous Chef

Paul Prudhomme intertwined Cajun and Creole philosophies, which is why you are

more likely to see both gumbo filé and okra both used in gumbo today.

PROTEINS AND GUMBO Z’HERBES

PROTEINS AND GUMBO Z’HERBES

The beauty of gumbo is not the roux, or even

the presence of okra and how much it is cooked down, but the freedom of using

any protein (or none) in the dish. Gumbo Z’Herbes is a vegan, plant-based gumbo

comprised literally of a melting pot of greens cooked down over an extended

period of time and served over rice.

This version of gumbo was made popular by the

Catholic Religion and consumed during Lenten on Holy Friday, a day when

followers of the faith abstain from meat products.

THE PROCESS

The secret to making a great Creole-style

seafood gumbo truly relies on the process in which items are added to the pot.

In any recipe, it is important to gather and prep all ingredients ahead of

time. This will ensure that everything is on hand and ready to be added. Save

the ends of the vegetables and shrimp shells to create the stock.

Begin with cooking down the okra, which can

take as long as, if not longer, than your roux. Stir frequently to ensure the

okra does not stick to the bottom of the pot, and periodically add water to

help break down the okra. When it’s done, it will look like a paste. Set aside.

Begin making the roux by whisking the flour

and fat constantly over medium heat. As soon as the color and sweet smell of

perfect gumbo roux is right, mix in the onion, celery, and bell pepper. This

process opens up your aromatics while simultaneously cooling down your roux and

stopping it from continuing to get darker.

Add Tomato sauce and okra paste and mix well.

Combine with equal parts stock and water by slowly adding water to the roux and

paste mixture, making sure the mixture is thoroughly incorporated. Add

seasoning, gumbo filé and bay leaves and bring to a boil, stirring periodically. Let

cook on a rolling boil for a minimum of four hours.

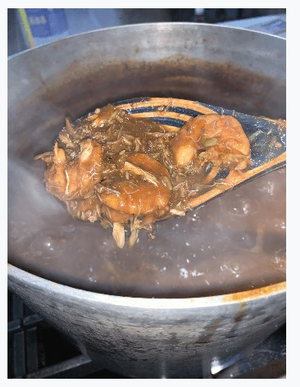

Add in protein at any point. Some prefer the

protein to be cooked down completely, while others like to see it. This is

optional, although there is a certain sweetness that shrimp and crab will add

to the dish when cooked down with the gumbo.

One secret that everyone should know: Let

gumbo sit a day before consuming. The chemical reaction that happens when gumbo

cools down and is heated back up does something magical to the dish that makes

it infinitely better than the day before. It is best served a day later with a

scoop of rice, corn mash/cornbread, or potato salad.

Next time you grab a bowl of gumbo at your

favorite spot on the island, think about what goes into making it and savor

every bite. It is a culinary masterpiece that is truly All American.

We would love to see what you create! Show us

your creations by tagging us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter using hashtag:

#galvestonmonthly #cookinlikeconcetta

Concetta Maceo-Sims is a 3rd

generation Galvestonian with a colorful family history in the food and

entertainment industry. She works aside her father at Maceo Spice & Import

Company at 2706 Market Street

where she develops new recipes, caters, and maintains the shop. She credits her

elders for developing her palate and love for cooking, as she grew up observing

them in their element. Luckily, she picked up their kitchen secrets and is

willing to share them!