In

Part I of this series, May 23, 1871 was stated as the date of the formation of

the paid fire department, when this was in fact the date of the official

reincorporation of the volunteer department after the Civil War. By the 1880s, more than

twenty volunteer fire companies operated throughout Galveston. Although they all had served the

city valiantly since the volunteer department was established in 1843, the

city’s exponential growth over the latter half of the 19th century

demanded a sanctioned municipal department.

The earliest request for a paid department

was voiced over a decade prior to its formation, when on May 26, 1873, Alderman

Mosebach presented a three-part resolution to the Board of Aldermen (City Council).

It stated that “no more fire or hook and

ladder companies be accepted or commissioned, with a view of organizing a paid

department…. all pay to volunteer companies, except feed for horses, driver’s

wages and other necessary expenses, be…hereby abrogated, [and] after the

expiration of the present year the chief of the fire department shall receive

no pay for his services whatsoever.” Only the second of these resolutions was

passed, however, and the volunteer department retained its duties.

It stated that “no more fire or hook and

ladder companies be accepted or commissioned, with a view of organizing a paid

department…. all pay to volunteer companies, except feed for horses, driver’s

wages and other necessary expenses, be…hereby abrogated, [and] after the

expiration of the present year the chief of the fire department shall receive

no pay for his services whatsoever.” Only the second of these resolutions was

passed, however, and the volunteer department retained its duties.

The issue came up once again one year later

when two volunteers were brought up on charges of arson, forcing the board to

amend the department’s governing ordinance to ensure stricter regulations and

grant the city permission to remove members from the volunteer company in the

case of misconduct. An op-ed in the Galveston Daily News conveyed the

fallout from this event and subsequently argued that a paid force would elevate

the department with “superior discipline, efficiency, and obedience.”

The article lauded the volunteers as “a

preeminently efficient department of its kind,” but also contended that

“nothing less could be expected from a department in the pay of the city than a

strict compliance with every requirement and detail of duty.” The economics of

the situation also belied the soundness of the volunteerism structure - financing

the numerous companies cost the city $35,000 per year (nearly $800,000 today).

Another important factor was a marked difference

in the efficacy of the two systems. Galveston’s

rapid expansion both in population and cityscape increased the ever-present

threat of conflagration. Volunteers were scattered, often mid-labor or consumed

with other daily activities when the alarm sounded, delaying their response

time. A paid department with full-time staff would be always at the ready, and

yet residents and city officials continued the discourse intermittently over

the next eleven years before any action was taken.

Another important factor was a marked difference

in the efficacy of the two systems. Galveston’s

rapid expansion both in population and cityscape increased the ever-present

threat of conflagration. Volunteers were scattered, often mid-labor or consumed

with other daily activities when the alarm sounded, delaying their response

time. A paid department with full-time staff would be always at the ready, and

yet residents and city officials continued the discourse intermittently over

the next eleven years before any action was taken.

Finally, in the summer of 1885, five aldermen

were appointed to a committee tasked with researching the potential viability

of a paid department. They presented their findings to council on September 21,

1885, recommending that the transition to a full-time department begin

immediately. They also presented an ordinance to guide the reorganization of

the Galveston Fire Department and govern it thereafter.

The ordinance provided for three steam fire

engine companies, one hook and ladder company, two hose companies, and one

supply hosecart [sic] and hose company combined. It allocated annual

salaries of $1,600 for the chief engineer (fire chief) and $900 for the

assistant engineer, both of whom would be appointed by council, as well as

monthly salaries of $90 for each of three engineers, $65 each for three engine

drivers, $50 for two hose company drivers and three hosecart drivers, $65 for

one hook and ladder driver and one supply hosecart driver, and $60 for one

tillerman.

The ordinance provided for three steam fire

engine companies, one hook and ladder company, two hose companies, and one

supply hosecart [sic] and hose company combined. It allocated annual

salaries of $1,600 for the chief engineer (fire chief) and $900 for the

assistant engineer, both of whom would be appointed by council, as well as

monthly salaries of $90 for each of three engineers, $65 each for three engine

drivers, $50 for two hose company drivers and three hosecart drivers, $65 for

one hook and ladder driver and one supply hosecart driver, and $60 for one

tillerman.

Additionally, six hosemen for engines, six

men for the hook and ladder company, and eight hosemen for two other companies

would each be paid $50 per month. All these positions were to be nominated by

the chief engineer and approved by the City Council with a majority vote of the

aldermen.

The various volunteer fire companies had been

headquartered in leased, makeshift structures and locations across the city - anywhere

they could find that had sufficient empty space to house fire wagons and

equipment, such as sheds, barns, garages, and in one instance, even a strip of

sidewalk outside a local business. But naturally, the formation of an official

city department required permanent residences for both crew and machinery.

At the outset, three fire stations were

established. The first Central Station (or Station 1) was set up at 2308-2312 Avenue

E (Postoffice Street)

in the 1877 firehouse constructed for the volunteer Hook and Ladder Company No.

1. Station 2 was placed at 1718

Mechanic Street, and Station 3 was located at 2512 Church Street.

After the Church Street station was damaged in the

1900 Storm, a new structure was constructed at 2828 Market in 1903, out of

which Station 3 operated until 1968. Central Station and Station 2, however,

were both moved in 1916 to the renovated and repurposed Old City Hall,

as it was dubbed after the opening of the current City Hall building on 25th Street

that same year.

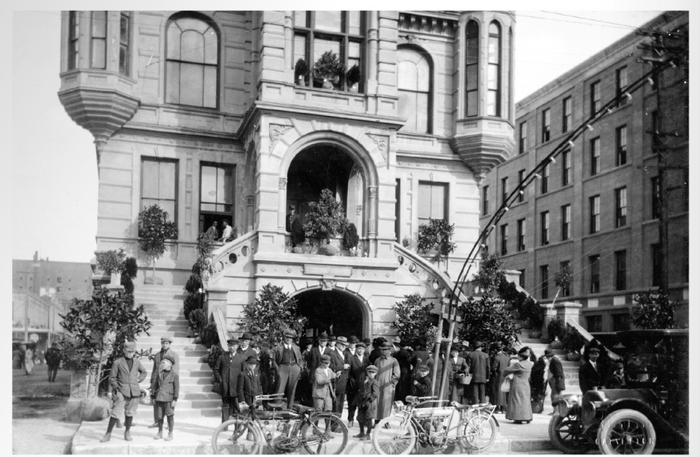

Originally an extravagantly ornamented

building, constructed as a testament to the city’s 19th century

reputation as “The Wall Street of the South,” much of Old City Hall’s grandeur

had been erased by the Great Storm, and its prominence was ultimately converted

into practicality.

The cornerstone for German architect Alfred

Mueller’s stunning “part Renaissance and part Iconic” design was laid on March

2, 1888. The mammoth three-story structure ran the length of two city blocks,

located on the central corridor of 20th

Street between Strand

and Market Streets. Its interior housed a farmer’s market on the first floor

and city offices and meeting forums on the second and third, but the

seriousness of these internal operations was encased by splendid architectural

novelty.

The north side of the building facing the Strand featured a pair of grand staircases that bypassed

the first level entrances and led straight to the municipal operations on the

second floor. These led to a center portico from which rose a 108-foot belfry

clock tower topped with a 30-foot pinnacle and flanked with four Romanesque

statues representing patriotism, courage, honor, and devotion. Elegant archways

on the first and second floors pristinely complemented the third floor which

boasted massive arched windows and corners punctuated with ornamental oriels.

Despite sustaining major damage during the

1900 Storm, which toppled the bell tower and sheared most of the third floor

from the building, Mueller’s City Hall provided refuge for hundreds on that

disastrous day. The building was also a witness to the early ideas of Galveston’s most

forward-thinking citizens who convened there to reorganize a defunct city

government, made even more so in the aftermath of the storm, into an entirely

new commission form of government.

The commission template styled the city

government after a business with a board of directors, and it was so effective

that it was adopted by numerous other American cities. Unfortunately, it also

proved itself prone to corruption and was replaced with the current

mayor-council-manager structure in 1961.

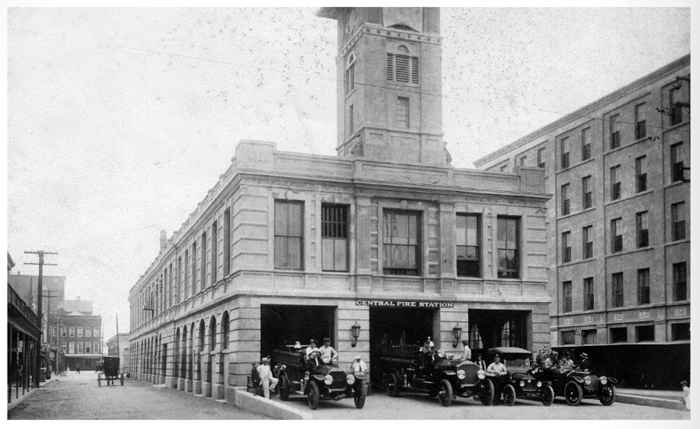

Mueller’s masterpiece was also dismantled

within that decade, although it had long since been a shadow of its original

incarnation. After the new City Hall was completed, it was converted into a

joint Police Station and Central Station of the Galveston Fire Department. What

remained of the third floor was removed, along with all distinct elements of the north façade including the bell tower,

staircases, and archways.

The crews of both Station 1 and 2 operated

out of the 20th Street

Central Station until 1965, when the penultimate Central Station (currently

undergoing demolition) was constructed behind City Hall at 2514 Sealy.

Galveston Fire Department historical data and photos courtesy of Austin

Smith, GFD Historian.