The magnitude of destruction

and suffering caused by the worst fire in Galveston’s

history was undoubtedly catastrophic in measure, but the potency of its memory

is further amplified by the eerie collection of circumstances surrounding it.

Firemen were (and are still) deeply superstitious about the number 13 and the

thirteenth day of the month - in the 19th century it was called

“hoodoo day” (a form of voodoo).

The fire broke out in the early morning, mere

half an hour after the clock struck November 13, 1885. It was also a Friday.

The fire originated at a foundry called Vulcan Iron Works, named after the

Roman god of metalworking.

Vulcan is also the god of fire, and his

descent upon the island happened to come on a quintessential island autumn day

- when sustained 30 mile-per-hour winds were gusting up to 40. As for the men

tasked with subduing this ferocity, Galveston’s

paid fire department was not yet two months old. A mere infant but

nevertheless, old enough to be baptized.

A patrolman on the east side of the city was

canvassing his beat, a route that eventually led him past Strand and 16th

Streets around 12:30am, when and where he noticed flames coming from the

metallurgy shop on the northwest corner. The tales of what followed this

discovery vary.

The one constant is that the newly

established Galveston Fire Department was efficient and timely in their

response to the alarm. However, some claim that the alarm was sounded promptly

while others decry that notion and insist that it was somehow delayed, perhaps

intentionally.

Regardless, the voracious winds made minutes

irrelevant. Within twenty minutes of the first alarm, forty-two blocks of the

city’s east end had been ignited as sparks and blazing fragments of wood were

carried far from their place of origin. The fire was then fueled by a veritable

feast of wooden shingles and structures in its path as the brutal north wind

pushed it southward and to the west.

Regardless, the voracious winds made minutes

irrelevant. Within twenty minutes of the first alarm, forty-two blocks of the

city’s east end had been ignited as sparks and blazing fragments of wood were

carried far from their place of origin. The fire was then fueled by a veritable

feast of wooden shingles and structures in its path as the brutal north wind

pushed it southward and to the west.

Once the fire overtook Market Street, two blocks south of its

origin, the Galveston

community’s trademark resilience was on full display. By that point, everyone

had forgotten entirely about calling the fire department. They were too busy

fighting the fire right beside them.

The quickness of a conflagration, however, is

conversely proportionate to the amount of time needed to extinguish it. The GFD

and its honorary civilian members battled for twenty-four hours, their efforts

badly impeded by a vastly insufficient waterworks system.

After Market Street, the fire had pushed on to Postoffice Street,

destroying everything between 16th and 20th Streets

except fittingly, the Post Office itself. The brick building had been built as

fireproof as was possible at the time; only the rear wall was badly burned with

no interior losses.

The next to ignite was Church Street, and then the fire

continued its southerly route towards the residential areas and municipal buildings.

It threatened the county jail, and the prisoners were readied for evacuation

although the brick structure and slate roofing ultimately resisted the blaze.

The courthouse was badly damaged, although

not nearly the total loss of its neighbor, the massive Exchange Hotel which was

consumed in a matter of seconds. The fire ripped through some of Galveston’s finest homes

as it continued toward Broadway

Avenue where it decimated the $25,000 Leon Blum

estate ($720,000 today).

Homes, schools, office and apartment

buildings, and sheds crumbled into ash. Telephone, telegraph, and fire alarm

wires snaked through the streets as their support poles toppled to the ground.

The fire was so hot that even the toe planks between the rails of the city

streetcar were burned, along with nearly one thousand feet of firehose as

sparks rained down on the firemen and their apparatus.

People poured into the streets, carrying

anything they could grab on their way out. The Daily News reported that

it would have almost been a comical scene - people scurrying about in their

nightclothes with lamps and bedside tables - had it not been for the gravitas

of the situation.

People poured into the streets, carrying

anything they could grab on their way out. The Daily News reported that

it would have almost been a comical scene - people scurrying about in their

nightclothes with lamps and bedside tables - had it not been for the gravitas

of the situation.

Astonishingly, only one life was lost. An

elderly man identified only as “Old John” suffered from consumption and was

laying in hospice at a house at 19th and Postoffice. By the time

neighbors remembered his condition and whereabouts and sent someone to retrieve

him, he had passed away, presumably from shock or smoke inhalation since his

body had not been burned. He was carried out of the house in a coffin against a

ghostly backdrop of a charred street and a sky that glowed crimson from the

flames and embers.

Around 7pm, the fire was finally contained at

Avenue O, but the inflamed structures continue to burn for many more hours.

Weak and weary firemen battled on, “grilled with the heat and stifled with

smoke, drenched with cold water and steamed with hot, soaked to the very pith

and marrow of the bone, until by efforts almost superhuman they had brought

under control the greatest fire in the city’s history.”

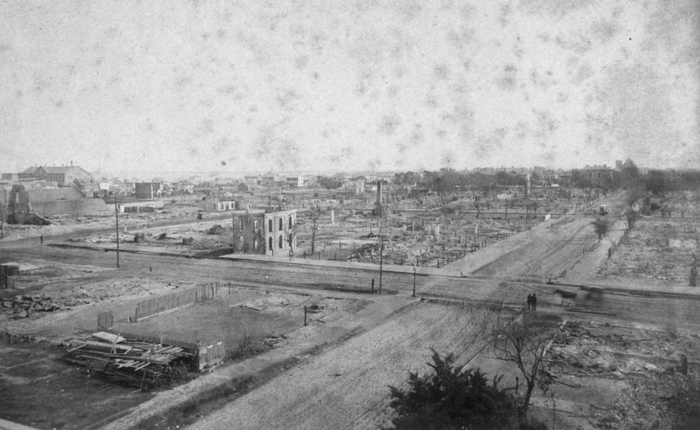

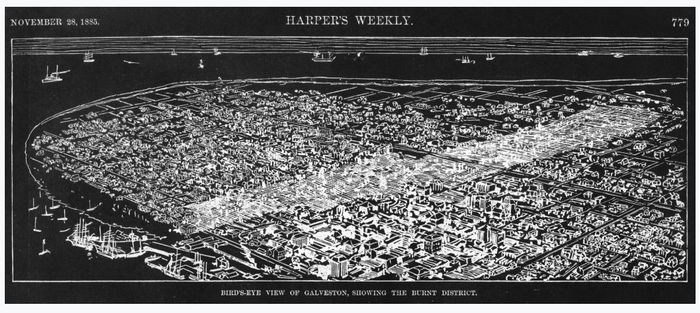

After the last flame was extinguished, the

Great Fire of 1885 had swallowed nearly one hundred acres of a densely

populated residential and commercial area. From the north side of the Strand to Avenue O, ranging in width from two to four

city blocks between 16th and 20th Streets, forty-two city

blocks and 568 homes were destroyed. An estimated 500 families, or more than

two-thousand people, were rendered homeless.

After the last flame was extinguished, the

Great Fire of 1885 had swallowed nearly one hundred acres of a densely

populated residential and commercial area. From the north side of the Strand to Avenue O, ranging in width from two to four

city blocks between 16th and 20th Streets, forty-two city

blocks and 568 homes were destroyed. An estimated 500 families, or more than

two-thousand people, were rendered homeless.

Every available vehicle - carriages, drays,

carts, wagons - were employed in the service of moving furniture and other

household goods that could be salvaged. They creaked slowly and solemnly down

streets lined with smoldering heaps of ash with only the chimneys left to

indicate that here once stood a house. Hundreds of houses along the fire’s

perimeter sustained damage as well.

The streets that bordered the burned areas

were lined with burning mattresses and wooden shingles that had been ignited by

sparks flying onto houses and into windows. They were thrown into the street to

save the house.

One of the largest non-structural losses was

that of a book collection belonging to a former mayor, J.C. Fisher. He was

lauded as having the largest collection of literary and scientific volumes in the

city, one that had taken decades to amass.

Unfortunately, the fire spared not one work.

The collection was not insured and was a total loss. All told, the city and

residents’ losses totaled $1.5 million, more than $43 million today.

Unsurprisingly, Galveston responded with its usual tenacity

and resilience. Houses were still burning when signs began to appear on vacant

buildings, “The poor and suffering can find shelter here for themselves and

their goods.” Colonel W.H. Sinclair, owner of the Beach Hotel, opened his

establishment as temporary lodging for displaced residents. Donations were made

by sister cities, and even Chicago donated money

to Galveston,

knowing full well the ravages of fire.

Unsurprisingly, Galveston responded with its usual tenacity

and resilience. Houses were still burning when signs began to appear on vacant

buildings, “The poor and suffering can find shelter here for themselves and

their goods.” Colonel W.H. Sinclair, owner of the Beach Hotel, opened his

establishment as temporary lodging for displaced residents. Donations were made

by sister cities, and even Chicago donated money

to Galveston,

knowing full well the ravages of fire.

A community relief fund was established with

Colonel W.L. Moody serving as treasurer. A traveling troupe of actors, The

Mikado Opera Company, performed a benefit performance of Gilbert and

Sullivan’s The Mikado, sponsored and hosted by Henry Greenwald, the

lessee of the opera house. One hundred percent of the proceeds were donated to

the relief fund.

The Galveston City Council earmarked $15,000

for the abatement of suffering among the victims and most importantly,

proceeded with improving the waterworks system, upgrading fire department

equipment, and enacting resolutions for preventative measures against future

fire.

In addition to mandating that all

construction use slate roofing to prevent fires from spreading, city officials

approved $450,000 for the installation of 13 brackish wells along Winnie Street at

800-foot intervals. The intricate system was comprised of 17,000 feet of water

mains, a pump house, and a standpipe system.

Despite the scope of the calamity, or perhaps

because of it, Galveston

learned from its mistakes and rebounded valiantly, just

as it had done after the Civil War and as it would do many more times in the

future.