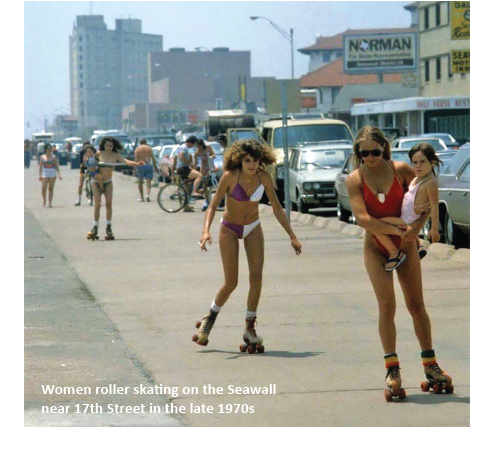

Anyone who has lived in or visited Galveston in the last 50 years has most likely seen skaters on the seawall. The popularity of the sport comes and goes, but its history on the island goes back surprisingly further than one might think.

America’s first roller skating rink opened on the East Coast in 1866, and the craze quickly spread west. George Plimpton’s invention of a four-wheeled “rocker” design that made it easier for people to turn by leaning left or right, added to the popularity.

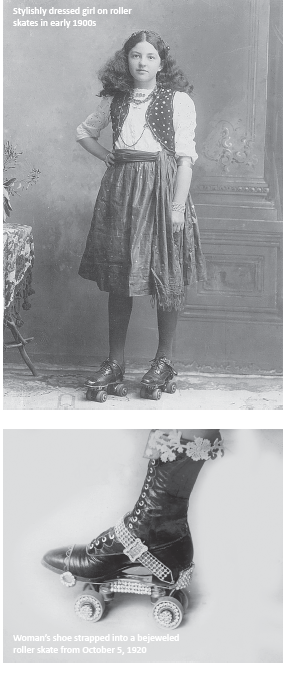

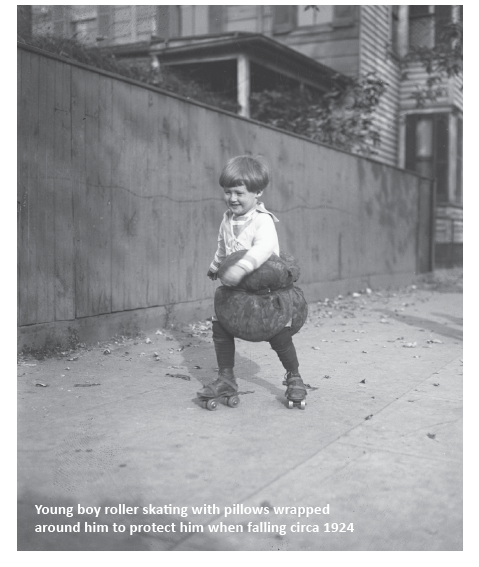

The wheels were attached to boards shaped to accommodate different shoe sizes. Leather straps were used to attach the skates to customers’ shoes. The sport was referred to as “rinking” when practiced in indoor halls.

By 1871, Galveston had its own skating rink which operated at Turner Hall on Sealy Avenue. It was complete with an on-site skating instructor who offered classes each morning and evening.

Occasionally, other local gathering places with dance floors, such as Trube Hall, Schmidt’s Hall, and Casino Hall, offered special skating nights that alternated with dancing. Live music at Turner Hall was provided by Scott’s Quadrill Band.

Traveling exhibition skaters like the famous Moe Brothers included Galveston on their tours, and their stunt-filled shows helped to create excitement around the sport. Vaudeville shows that appeared at the Opera House also began to include both skillful and comical skating acts.

Public skating nights for ladies and gentlemen were held each week on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday in Galveston. Special “carnival nights” were occasionally held that required attendees to come in costume. Entrance to these events cost 50 cents per person and were often organized as fundraisers for local benefits.

Roller skating was especially popular with young adults because pair skating allowed the participants to converse without chaperones or friends overhearing each conversation. It also inevitably required the holding of hands for support. Both of which would not have been publicly acceptable in other circumstances.

It was also a chance for people of different levels of society to mingle with each other, from the children of millionaires to the offspring of the working class.

With little experience in roller skating, Galvestonians were bound to have mishaps that were novel enough to be reported in the local newspaper. One such incident included a visiting gentleman who fell moments after putting his skates on and broke his leg in two places.

Other accounts were humorous such as that of a woman who, when losing her balance, called for everyone to “look away.” Of course, no one did, and the ensuing somersault that revealed the color of her striped undergarments was gleefully reported.

As the 1880s arrived, roller skating had become so popular that customers wanted to own skates rather than rent them, and local merchants happily obliged. Baldinger Brothers on Mechanic Street carried skates for adults and youngsters. Mason’s book and stationery store on Market Street acquired 100 pairs of “parlor skates” to sell to its customers.

The increasing number of skaters warranted the construction of a facility designed specifically for the sport. In September 1884, Michigan native S. D. Felt leased ground from a local railroad company at Avenue Q and 24th Street, where a roller coaster once stood, and made plans to build Beach Rink Park. He opened a rink in Houston at the same time.

Considered one of the finest rinks in the Southwest, the $4,000 Beach Rink opposite the Beach Hotel was a spacious building that included washrooms, coat and hat rooms, seating for spectators, interior lights for night skating, colored lanterns for decoration, young male attendants to adjust and remove customers’ skates, a highly polished, imported maple floor, and the latest “New Era Skates.”

The Beach Rink drew large daily crowds, with regular skating sessions from 10 a.m. until noon, 2:30 to 5:30 p.m., and 7:30 to 10:30 p.m. A live band furnished music for the afternoons and evenings.

Local champions emerged in communities, including a Galveston supply clerk named Edward Knowles, and competed against each other and visiting professionals.

St. Clair Millard, a winner of multiple skating trophies in Houston, came to the island to challenge a local skater named Pedder in January 1885 to a three-mile race, with 17 laps per mile. Though Millard used the Plimpton-style skates that were by that time considered old-fashioned, he once broke a record by roller skating 100 miles in 11 hours and 46 minutes.

St. Clair Millard, a winner of multiple skating trophies in Houston, came to the island to challenge a local skater named Pedder in January 1885 to a three-mile race, with 17 laps per mile. Though Millard used the Plimpton-style skates that were by that time considered old-fashioned, he once broke a record by roller skating 100 miles in 11 hours and 46 minutes.

Not wanting to chance a Houstonian outperforming a Galvestonian, the staff of the rink greased the track with a substance that would not affect Pedder’s skates but would cause his rival’s wheels to seize. Pedder won.

In April 1885, Dan Johnson opened the first rink for the African American community of Galveston in the Jordan Building on The Strand between 19th and 20th streets. Admission was 25 cents, which included the use of skates.

The Beach Rink was destroyed in August 1886 by the Indianola Hurricane, which was named for the coastal town that it devastated. That left the market available for other rinks to open, including the Galveston Skating Rink on the northeast corner of Tremont Street and Seawall Boulevard which opened the next year.

Even the Tremont House joined in the trend by fitting its billiard hall at the rear of the hotel as a private rink and opening it as a place for members only in 1887.

Skating waned in popularity in Galveston during the 1890s but regained its footing after the 1900 Storm.

The Galveston Auditorium Rink on the southwest corner of Avenue Q and 27th Street opened in 1903 and provided welcome entertainment to an island working to recover from the horrific hurricane.

In January 1905 the Palace Skating Rink opened under the proprietorship of Leroy R. Love, on the second floor of 2324 Market, over the Palace Bowling Parlor. Many of the attendees on opening night had never worn a pair of skates before, which provided comical entertainment to onlookers.

Richardson Ball Bearing Skate Company from Chicago advertised in the local newspaper that year, alerting Galvestonians: “If you can secure a building suitable for roller skating, do so quick. It's the game that gets the money.”

By the following year, at least four roller skating rinks populated the island. The Galveston Roller Rink Company’s Beach Skating Rink, managed by George N. Gorham, was located on the northwest corner of Tremont and Avenue Q. The Auditorium Roller Rink was located on the south side of Avenue Q between 27th and 28th streets.

The two other skating rinks were both for African American customers. Lincoln Hall, managed by Robert Williams and owned by Frank Malloy, was located at 2924 Avenue H. The Oleander Skating Rink and Amusement Company, managed by E. S. Johnson, was located at 3001 Winnie Street.

The two other skating rinks were both for African American customers. Lincoln Hall, managed by Robert Williams and owned by Frank Malloy, was located at 2924 Avenue H. The Oleander Skating Rink and Amusement Company, managed by E. S. Johnson, was located at 3001 Winnie Street.

Malloy, an undertaker and owner of local livery stables in addition to owning Lincoln Hall, applied for and received a liquor license to serve beer at his new dance and roller-skating hall. Unfortunately, it was not known at the time that the venue was built in a “resistance area,” one that was against drinking. The license was revoked, but again granted to the Oleander Skating Rink a year after Malloy purchased that location.

Situated in a residential district, Lincoln Hall was repeatedly protested for many years by the neighborhood because of loud noise that lasted until midnight every night. It closed after seven years.

Of these rinks, the Auditorium was the most popular. At its grand opening in April 1906, between 300 and 400 people crowded the hexagonal floor.

Skaters were eager to try out the new roller-bearing, nickel-plated skates that featured straps that adjusted with keys for a perfect fit. The proceeds from that night were donated to the Women’s Health Protective Association for the planting of trees to beautify Galveston streets.

Voight’s City Band provided the music as customers skated in called programs of couples, singles, women-only, and men-only rounds. A large gong was used to signal the changes of program as well as warn over-zealous attendees if rules for speed or courtesy were not being observed.

Voight’s City Band provided the music as customers skated in called programs of couples, singles, women-only, and men-only rounds. A large gong was used to signal the changes of program as well as warn over-zealous attendees if rules for speed or courtesy were not being observed.

The rink was open daily and was free in the morning hours but cost 10 cents in the afternoon and 15 cents at night in addition to a 25-cent skate rental fee. Skating instructor William Zingelmann provided lessons.

After 10 o’clock on Monday nights, the private Monday Night Skating Club (whose members included prominent names such as Willis, Sealy, Ujffy, Ladd, Trueheart, Kempner, Moody, and Vidor) was allowed to skate until midnight.

Prizes were awarded during regular skate contests that tested competitors’ speed and creativity. Often awarded were: Oriental vases; vanity sets or gold bracelets for ladies; boxes of cigars, jeweled lighters, or pocketknives for men; and toys for children.

The competitions involved wearing skates while performing three-legged races, barrel racing, lap skating, skating with a dog, and trick skating. Other categories that qualified for prizes might be the tackiest costume, most comical costume, most graceful skater, and a category called “whole damn family” that required entire family units to perform combinations of the above.

One man took three leaps over a set of chairs, skated on 16-inch-high stilts, and skated on one foot through a ring of fire. It was later revealed that he was a professional.

Maco Stewart, Jr. was credited with devising a “card skating” exhibition in 1906 that was received so well by audiences it was repeatedly performed at several fundraising events. The skate consisted of 30 adults who wore over-sized, card-theme sandwich boards, and the face cards were worn by children. One spotlight trick skater would appear as the joker of the deck.

Because it was not unusual for the Auditorium Skating Rink to have 200 customers on a weekend night at the time, the owners requested permission from the city to remove the seats on the south side of the auditorium to provide more skating surface as well as remove posts and trusses and add ventilation to that wall.

The request was denied because such changes would compromise the building, but the owners were allowed to make screened openings in the south wall for ventilation.

Built in the spring of 1906, the new Beach Rink featured an ice cream parlor with a fountain apparatus on the ground floor. In the early morning hours of November 25 that same year, the wooden structure was lost to fire, along with a rooming house directly behind it.

Built in the spring of 1906, the new Beach Rink featured an ice cream parlor with a fountain apparatus on the ground floor. In the early morning hours of November 25 that same year, the wooden structure was lost to fire, along with a rooming house directly behind it.

Grade-raising canals with pontoon bridges which were still being used for the over island raising prevented the fire department’s steamer engine from reaching the site.

In the following days a crowd of small boys dug through the ruins to discover things. Several hundred pairs of skates, including those of regular customers who stored them at the rink, were either melted or burned. Only one pair of skates, which belonged to Eddie Barr, survived and were returned.

About this same time in 1906, boys and girls who now owned their skates took to enjoying their hobby daily along the neighborhood sidewalks of the East End.

One disgruntled resident objected and had several large signs printed, that read: “This sidewalk is not a playground and skating is strictly prohibited.” The children doctored the signs to read “This sidewalk is a playground and is the best skating in town.”

Grumpiness prevailed, and by the following February, an ordinance was passed to prohibit skating on Galveston city sidewalks. The fine for each offense was five dollars, for which the parents were liable if the perpetrator was under 13 years of age.

In 1907, the Auditorium was updated with new flooring, extra lighting, and new skates and re-opened in June as Huddleston’s Rink. It was named for Barbara Huddleston by her brother John Nicholas Haag. The two were the new lessees of the rink.

By Christmas of that same year, it had been redubbed the Zoo Skating Rink, and was operated in connection with the Parker Circus. Trained wild animal performances were held in between skating sessions each day.

At intervals of 30 minutes, trained animal demonstrations were given in a steel cage on the rink’s stage daily. Shows included several male and female lions and a troupe of trained black bears handled by La Bell Rosa, one of the foremost female animal trainers of the time.

Regardless of the successions of names held by the rink, locals continued to refer to it as the Auditorium. The structure was also used to host the city’s Saengerfest Festival before the city auditorium was built.

In 1910, Leon Brownie, the former proprietor of the Electric Park merry-go-round, leased a somewhat triangular lot bounded by Tremont Street, Avenue Q, and Seawall Boulevard (where Wendy’s restaurant on the seawall is currently located) on which to build a new amusement complex.

It would become a combination of attractions in a two-story stuccoed concrete building. He installed the merry-go-round he previously operated at Electric Park at the back of the lot.

Brownie petitioned successfully for the removal of the fountain on Tremont Street between Avenue Q and Seawall Boulevard to allow for the project. The city paid for the removal and Brownie paid for a new sidewalk.

The first floor of the attraction included a skating rink, bowling alley, shooting gallery, billiards hall, chop suey café, and several concessions. The most unique feature of the rink was an invention called the “skating whirl” which consisted of a section of the waxed skating floor and a carousel mechanism with hanging straps. The skaters would grasp the straps and the mechanism would pull them in circles at increasing speeds.

The second floor, which included an expansive dance floor with a bandstand and a restaurant, was modeled after Coney Island attractions where diners could leave their tables in between courses to dance before returning to their seats to continue eating.

A roof garden offered seats and tables that faced a stage where summer vaudeville acts could perform, or moving pictures could be shown. Customers could also request restaurant service on the top level.

The first appearance of roller skates on the big screen was in the Charlie Chaplin film, "The Rink," which was released in 1916. The comedy helped to re-popularize skating, carrying it well into the 1930s.

The first appearance of roller skates on the big screen was in the Charlie Chaplin film, "The Rink," which was released in 1916. The comedy helped to re-popularize skating, carrying it well into the 1930s.

The hobby of skating found popularity again in the 1940s when locals went to Artistic Skating at 10th Street and Seawall Boulevard to enjoy the sport. Other rinks adopted versions of the Beach Rink name.

In the 1970s and 1980s, an entirely new generation skated and rollerbladed along the seawall, listening to music that they could now carry along with them.

Today both skating and rollerblading are enjoyed by long-time and newfound devotees who enjoy sailing through the Galveston sunshine on wheels atop the seawall.