In the decades prior to the widespread popularity of automobiles, Galveston had benefitted greatly from the Texas cotton industry which had verifiably boomed after the Civil War. The small island city became one of the most successful and dominant commercial ports in the world, a reputation that lasted well into the 20th Century.

To celebrate this indebtedness to their literal cash crop, as well as to draw visitors to the island, a group of prominent Galveston residents launched an annual Cotton Carnival in 1909. The three-day festival included a host of special events, but one of the most anticipated was a series of six automobile races.

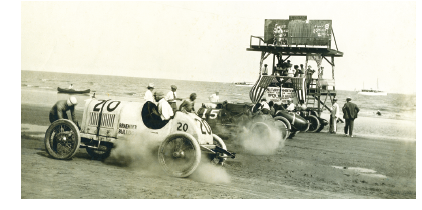

The races were loftily sanctioned by the American Automobile Association (AAA) and the track was a two-and-a-half mile loop located on Denver Beach (present-day East Beach) that began at Fort San Jacinto at the far eastern tip of the island and ran three miles westward.

Unlike street racing or straight-away tracks, Galveston promoters wanted to make sure that spectators did not miss a moment of the race, least of all the thrill that was generated when drivers approached the turns at breakneck speeds.

Despite the abbreviated distance of the track, races were held at a variety of intervals and difficulty levels; drivers could choose from one, two-and-a-half, five, or ten mile races. The grand finale was a grueling fifty-mile free-for-all.

The first day of the races beckoned an astounding fifteen thousand people to Galveston’s eastern shore. The intensity of the contest electrified the crowd as they strolled the hard-packed sand among a chorus of engines. Competing cars circled in and around the spectators prior to the races, the hand-polished chrome glinting and gleaming under the August sun as the drivers displayed both their bravado and the beautiful, finely attired women draped across their backseats.

The first day of the races beckoned an astounding fifteen thousand people to Galveston’s eastern shore. The intensity of the contest electrified the crowd as they strolled the hard-packed sand among a chorus of engines. Competing cars circled in and around the spectators prior to the races, the hand-polished chrome glinting and gleaming under the August sun as the drivers displayed both their bravado and the beautiful, finely attired women draped across their backseats.

Crowd control was a nearly non-existent concept at the time, however, and the policemen assigned to the task numbered only three. Their presence was therefore of no real consequence and proved entirely ineffective when the fifteen thousand began to encroach upon and over the ropes that bordered the racetrack.

Organizers momentarily feared that the very popularity of the race could be its undoing if the crowd did not make way for the cars to run, but since that was in fact the entire reason that they were there, the spectators eventually allowed themselves to be corralled and moved off of the track.

Two years later, in attempt to establish posterity for Galveston on the national racing circuit, a group of fifteen high-profile businessmen officially organized the beach auto races in 1911.

Each of the fifteen purchased five shares valued at $100 apiece as an investment in the capital stock of the Cotton Carnival Beach Racing Association, later changed to the Galveston Beach Racing Association. Contributors included Galveston legacies W.L. Moody, Jr., Maco Stewart, R. Waverly Smith, and Sealy Hutchings.

With each passing year, the racetrack was lengthened, and the contests were expanded to include first a 100-mile and then a 200-mile straightaway, free-for-all race and the excitement of the events together with the exquisite backdrop of Galveston Island continued to draw thousands and thousands of onlookers.

An official judge and flag stand was erected at the starting/finish line, as was a shaded grandstand that could seat over two thousand people.

An advertisement boasted, “Galveston has one of the finest beach speedways in the world. Thirty miles in length, absolutely smooth, hard-packed sand, where there is always a delightful ocean breeze. And best of all there is no dust. A drive along this roadway of nature is a tonic to man, woman, and child.”

For the drivers, that temperate ocean breeze added an inescapable nuance to their competition. Nineteen-year-old Tobin Dehemel from San Antonio told the local newspaper that it was the “swellest” track he had driven, but that “the wind blows so hard when you’re going a mile a minute or more that once open you can’t close your mouth. You just watch the road and the engine and once in a while, maybe, take a swift glance back to see how close they are to you…you don’t have time to get scared.”

In 1912, the national racing circuit was purposely slashed by half to increase competition within the individual races. Galveston made the cut, and the beach auto races continued as one of the city’s most lurid draws for the remainder of the decade, becoming so successful that they attracted drivers from as far away as Paris and even competed in popularity with Daytona Beach and Indianapolis.

Some of the participants in Galveston’s beach races would go on to establish themselves as forerunners of the automobile industry and racing circuit, such as sporting enthusiast Armour Ferguson, the wealthy daredevil Barney Oldfield, and three-time Indy-500 winner Harry Endicott.

In 1921, the Galveston County commissioners approved West Beach for the establishment of a new racetrack by the Galveston Beach Racing Association. But by the following year, Galveston had all but vanished from the national racing circuit, most likely at the hands of another strategic circuit reduction designed to concentrate talent and intensify the level of competition among drivers.

Despite the abrupt ending to what many had hoped would be an enduring legacy, the beach auto races, and the Galveston Beach Racing Association accomplished something far greater. The efforts of local car clubs like the GBRA were instrumental not only in perpetuating the popularity of the automobile, but also in the building of subsequent roadways to accommodate them.