Tucked away on the upper floor of Galveston’s historic Moody Mansion lies a treasure trove of family history, including thousands of artifacts collected over generations. Many of them were gathered by Mary Moody Northen herself.

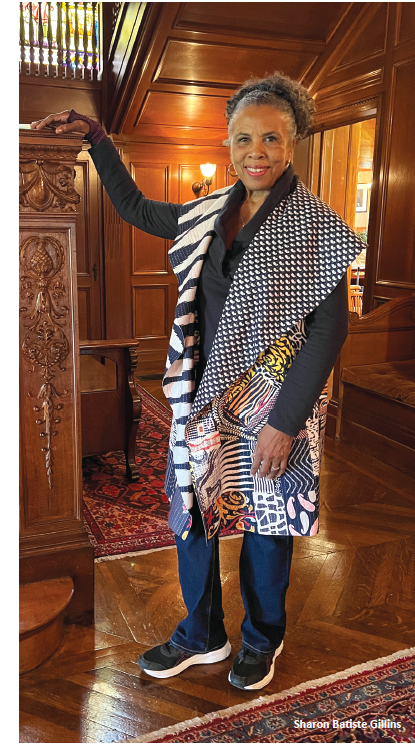

It’s a rich archive of objects, stories, and heirlooms that researcher Sharon Batiste Gillins helps illuminate through carefully curated rotating exhibits.

A Galveston native, Gillins left the island after high school to pursue college in Washington, D.C. She built a career in California as a telecommunications professor at Riverside Community College. After retiring, she returned home in 2011, unintentionally setting the stage for her next chapter.

At a party not long after her return, Gillins was overheard by Moody Mansion executive director Betty Massey discussing her passion for genealogical research. Intrigued, Massey invited her to work with the mansion’s extensive family archives. She has now worked there part-time for 13 years.

“The archive holds Moody family history dating back to the late 1790s,” Gillins explained. “It fills hundreds of boxes. I helped prepare the materials for appraisal before they were donated to the Galveston and Texas History Center at the Rosenberg Library.”

“I once saw a land document signed by Sam Houston in the collection. It goes back to Antebellum times. After completing that project, I transitioned to working inside the house itself,” she said.

While the Rosenberg Library now houses documents such as letters, photographs, and ephemera, many physical artifacts remain at the mansion.

Two former bedrooms once occupied by Moody sons have been transformed into exhibition spaces and currently feature a new display of Native American artifacts collected by Northen and curated by Gillins.

According to Gillins, the Moody team takes six to eight months from when an exhibit theme is decided upon to the opening of a new exhibit. Once a theme is decided, she delves into the collection inventory to locate pieces to help tell the story.

According to Gillins, the Moody team takes six to eight months from when an exhibit theme is decided upon to the opening of a new exhibit. Once a theme is decided, she delves into the collection inventory to locate pieces to help tell the story.

Each item is labeled with an accession number linked to filing cabinets filled with handwritten information sheets collected by previous employees and volunteers. The information is sometimes supplemented with further research by Gillins.

"The most incredible thing about Mrs. Northen, aside from the fact that she collected these things, is that she left us notes about them. She often noted where she got the item, how much it cost, and other details. She was an archivist without knowing it.”

Gillins utilizes this information to create interpretation cards for the displays and weave a story between the items.

Her workroom on the third floor is not as grand as the mansion's public rooms, but it is a functional place to review treasures from the collection and plan exhibits. The collections she works with are on the third floor as well.

An object room houses innumerable items from Northen’s travels as well as an extensive collection of family items such as exquisite oyster plates, toys that belonged to Moody children, journals, calendars, ephemera from special events, a sewing kit, hand mirrors, and jewelry.

An object room houses innumerable items from Northen’s travels as well as an extensive collection of family items such as exquisite oyster plates, toys that belonged to Moody children, journals, calendars, ephemera from special events, a sewing kit, hand mirrors, and jewelry.

“She has Bing and Grøndahl Christmas plates that go back to the first one in 1895,” beamed Gillins about Northen.

The textile room is where anything made of fabric is stored and still sports a small brass door plaque noting its original use as the home’s theatre.

Glancing around the room, one might see racks of original and reproduction fabrics used in and created for the house, a Christmas tree skirt, rugs, original curtains, and even shoes. There are also boxes of clothing that various family members, including Northen, once wore.

Standing beside a beaded party dress once worn by Northen, Gillins points to a photo and shares this: “Here she is in that dress. She was very much into Mardi Gras.”

“Everything is climate-controlled. The textile room has one climate, the object room has a different climate, and the archive annex is also climate-controlled. And all the storage materials are archival stable materials.”

Once the items are chosen for an exhibit, the next phase of creating the exhibit begins.

Once the items are chosen for an exhibit, the next phase of creating the exhibit begins.

“The [previous] exhibit has to be taken down, all of those items have to be securely stored, assess the room to determine if we have the exhibit pieces that we need, and what changes need to be made to exhibit them securely.”

“Then we pull all the new items and determine if they are stable or need repair,” Gillins said.

She explains that because the collection is so extensive, if one of the pieces needs conservation, they will return it to storage and replace it in the exhibit with another piece rather than restore it. “There’s just so much in the collection, it’s nice to have a choice.”

In the 1990s, a museum director in Australia coined the term ‘streakers, strollers, and students' to portray the way museum visitors engage with exhibits.

Streakers move quickly through an exhibit, strollers take more time to look at items and read some of the available material, and students take more time to examine artifacts and read labels.

Members of the Moody staff utilize this method to design displays to appeal to each of these attention spans.

The work is never done. With one exhibit complete, plans for the next have already begun, and attention is paid to ongoing tasks.

“We're in the middle of a project to reorganize thousands of slides and put them into archival sleeves.”

“This family had some incredible values about saving their history. Four or five generations of their artifacts and documents tell a social and economic history of this city and the state, and to a large extent, this nation,” Gillins said

“I feel very fortunate to have such intimate contact with the items they left for us.”