The Carnegie Medal is awarded to civilians who risk death or serious physical injury to an extraordinary degree saving or attempting to save the lives of others. It was instigated by Pittsburgh steelmaker Andrew Carnegie, along with the creation of a hero fund.

The cartouche is adorned with laurel, ivy, oak, and thistle, respectively signifying glory, friendship, strength, and persistence – the attributes of a hero. A verse from the New Testament encircles the outer edge: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13).

Impressively, there have been nine Galvestonian awardees of the Carnegie Medal. Two that were among the earliest resulted from acts of bravery during a hurricane in 1909.

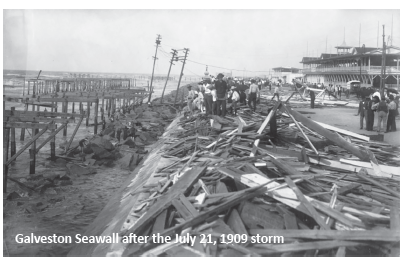

On July 21 of that year, a hurricane did extensive damage to the beachfront as well as destroying The Breakers and Murdoch’s bathhouses and Bettison’s Fishing Pier. Though no lives were lost on the island, 20 people died along the coast and five drowned at fishing piers. Four of those five were at Bettison’s. The toll would have been higher if it weren’t for the heroics of two men.

Charles Albert William Hansen was a 29-year-old deckhand aboard the pilot boat Texas. Born in Norway, he immigrated to Galveston at the age of 10 and had been working on boats since his boyhood. The five-foot, six-inch tall young man was accustomed to the hard work expected aboard ship. He earned about $45 per month.

Another immigrant from Norway, 28-year-old Klaus Louis Larsen, was one of his shipmates. A bit taller than Hansen at five-foot, ten inches, Larsen earned about $70 a month.

Both of the men regularly sent money to Norway to help support family members.

Bettison’s was erected over a granite block jetty seven miles east of Galveston and three miles from shore, over twenty-foot-deep waters. On July 20 the overnight accommodations at the small frame building atop the pier were filled with staff as well as guests, ready to take advantage of fishing at first light.

During that warm summer night, a storm grew in intensity, posing an imminent threat to anyone on the fishing piers. The jetties were soon covered with water and 20-foot waves were washing over the walkways of the pier and dashing against the walls of the building. The wind was blowing at a velocity of 36 miles per hour.

Meanwhile, the one hundred-twelve-foot-long pilot boat Texas, considered one of the best boats in the city, was at the Galveston docks with three pilots, a captain, and ten crew members. The pilot in charge was awakened, updated on the weather status and decided to take the boat to retrieve the endangered people at the piers. It was underway by four a.m.

Despite the Texas’ four hundred fifty horsepower engine, the force of the wind and waves prevented it from getting any closer to the pier than 75 feet, so Hansen and Larsen volunteered to man one of the sixteen-foot yawls to rescue the occupants of the pier.

As it was lowered into the water the yawl was tossed about like a toy, with waves breaking over the sides. With great effort, the two men rowed the boat toward the pier, but several times when they were within twenty or so feet of their goal the waves would toss them backward thirty to fifty feet.

One man on the pier shouted to the other stranded parties to come to the walkway in groups of four. The piles beneath it were already weakening and swaying in the wind and surf. As the men made their way out of the building, they grasped the railings to keep from being thrown into the water.

When the boat was finally within ten feet, a man on the pier tossed a life preserver attached to a line to it and pulled the boat four feet from the structure. They didn’t dare to bring the boat any closer due to the action of the waves that lifted it high above the wharf, then dropped it several feet below.

As each of the four waiting men saw their opportunity, they jumped one at a time into the yawl. Once each was aboard, the sailors guided the boat away from the pier with oars and back toward the Texas.

As they came alongside the pilot boat, Hansen and Larsen attempted to steady the craft as the others climbed a rope ladder to the deck above one at a time. The smaller boat was rising and falling in the water, so the men had to climb quickly to not get caught between the two boats and crushed.

After three such trips to the bridge of the pier, the men on board the Texas noted that the pilings were giving way and signaled to those on the pier to go to the other side, which they did. Just as the last of the men reached their goal, the pilings broke away like twigs, and that portion of the pier was swept away.

During some of the trips as men attempted to jump into the rescue boat, they fell into the water and would have to be pulled out. Each time this happened it allowed enough time for the craft to drift away from the others, causing Hansen and Larsen to have to row back toward them.

One of the men, who weighed about 240 pounds, fell into the water as he attempted to grab the ladder of the Texas, and quickly drifted 75 feet. Hansen and Larsen rowed the yawl after him and threw a rescue line.

When he attempted to climb aboard the small boat that was already partially swamped, it was in danger of capsizing. Additional ropes were then thrown from the deck of the Texas and fastened around the man, who was pulled aboard by the crew.

When he attempted to climb aboard the small boat that was already partially swamped, it was in danger of capsizing. Additional ropes were then thrown from the deck of the Texas and fastened around the man, who was pulled aboard by the crew.

The yawl made eight or nine trips in all, each lasting from fifteen to forty minutes depending on the force of the wind and waters, and the two sailors bailed water after each trip.

After their last trip, there were six men visible remaining at the pier when it collapsed into the water just before eleven o’clock. Hansen and Larsen watched as the others were thrown into the water. Seeing that each seemed to immediately catch a piece of wreckage, they called to the Texas to cast them loose so they could retrieve them.

The sailors rowed to the men in the water and pulled five aboard. Another man was pulled from the water by a line thrown to him from the deck of the Texas.

By the time all of the men and their rescuers were aboard the Texas, Hansen and Larsen were so tired they could barely walk.

Among the rescued were Joe A. Jones, a bank cashier from Somerville; Charles Schram, a nine-year-old schoolboy from Houston; musician Felix Schram from Houston; Charles Johnson, Bettison Pier's cook; Major N. T. White of Pine Bluff, Arkansas; W. Davies, a disabled guest from Groveton who had no legs, and thirty-two other men.

The owner of the pier, Captain Bettison, and his wife Gussie were among the lives lost, as were the wife of the cook Johnson and C. H. Dailey, circulation manager of the Galveston Tribune. Dailey’s body was never recovered.

Ernest Booth, a waiter at the pier was rescued from Morgan’s Point after being in the water for 36 hours.

Later a reward of $100 was collected from the rescued individuals and divided between Hansen and Larsen. They were also nominated for a Carnegie Medal in thanks for their bravery.

Both men later admitted, when asked by the Carnegie Committee, that they had risked their lives. Each received a bronze medal and the sum of $1,000 from the Carnegie Hero Fund, with the stipulation that the money be “soberly and properly used.”

Hansen’s goal had been to save $700 to pay his way through a navigation school so he could earn a license as a captain and navigator, which the award money allowed him to do. After attending the Patterson Navigation School in New York City, he returned to Galveston and became the captain of the Texas and later of the Charles Clarke. He married Cordelia Maddox in 1917 and left Galveston with their child in 1922.

Larsen expressed his goal of purchasing a launch and taking up the occupation of fishing. Those goals were evidently realized as well, as his World War I draft registration card in 1918 listed him as a fisherman who owned his own launch in San Pedro, California.

The bravery of these two men changed the paths of so many lives and families and should never be forgotten.