As traffic moves down Broadway, many people glance through the windows of SunRay Patio Furniture, at the corner of 51st Street and Broadway, to admire the brightly colored offerings. Most don’t give a thought to the simple building SunRay calls home, or to the colorful history it holds.

Clues to the past are easily visible to visitors who enter the store, however, and those who work there are proud of the structure’s heritage.

It was built in 1911 to serve as the terminal stop and paint shop for the rail cars of the new Galveston-Houston Interurban Railway, which played a major role in the island becoming known as “Houston’s playground.”

Construction of the railway began in March 1910, and the last spike was driven on October 19, 1911. The first train drove across the new tracks the following month.

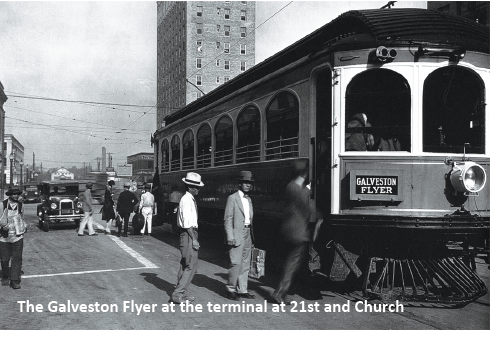

The electric-powered railway made the trip from the Rice Hotel in Houston, across the causeway, past stops at John’s Oyster Resort and the Galveston Downs racetrack, ending at the isle terminal at 21st and Church streets. This brought visitors from the mainland city to the island in 75 minutes.

The most famous car of the line was the popular Galveston Flyer which won the record as the fastest interurban in the United States in 1925 and 1926.

“Speed with Safety” was the Flyer’s slogan. A one-way fare cost $1.25 and a roundtrip ticket could be purchased for $2. The railway provided a convenient way to reach Galveston, increasing the success of tourism on the island.

The line operated until 1936, and at 1am on November 1 of that year, the Galveston Flyer pulled into the Galveston terminal for the last time.

After all of the interurban properties were disposed of, some locals resourcefully converted a portion of the former railcars into small homes. Additionally, the local Kiwanis club used wood from the seats to make 40 benches along the Seawall.

The interurban depot in downtown Galveston was later used for buses but was eventually demolished in 1982 after more than a year of vacancy.

The terminal building on Broadway continued to be utilized by a variety of companies. In the 1940s, it served as a storage location for Metropolitan Food Markets. Part of the structure was also used by the Coca-Cola Bottling Company as a sign-painting shop, storage, and place to repair coolers.

One of the building’s owners during that era was Frances Elizabeth Wisnoski Hooper (1898-1989). Ironically, Hooper was the daughter of a Polish immigrant who worked as a streetcar motorman in Houston.

Divided portions of the structure were later used by general contractors to mill lumber, store building materials, and as a laundry.

Divided portions of the structure were later used by general contractors to mill lumber, store building materials, and as a laundry.

Local architect Michael Gaertner explains that the edifice as it exists now consists of three buildings.

“The two buildings to the east are historic brick warehouse ‘mill-frame’ type construction of thick, masonry exterior walls and heavy timber frame interiors,” he explained.

“The third, westernmost building, is an addition of pre-engineered metal frame, dating to the time of the folded plate canopy which gives the building its unique mid-century modern appearance.”

In the 1950s, the building was occupied by ACME Roofing and Manufacturing, who were known for their ARAMCO aluminum blinds and storm shutters.

In the early 1960s, the company removed the original façade and replaced it with spans of plate glass windows to display their products, which became especially popular after the devastation of Hurricane Carla in 1961.

In the early 1960s, the company removed the original façade and replaced it with spans of plate glass windows to display their products, which became especially popular after the devastation of Hurricane Carla in 1961.

During a business expansion in 1971, an unprotected opening was cut in the firewall between the portion of the structure at 5101-5109 and the newer addition at 5111. While Aramco operated in one portion, a shoe store conducted business in another.

One portion of an original brick wall still shows damage on the interior from a grinder used in manufacturing the blinds.

In the early 1980s, the upstairs offices were used by a trophy and engraving company.

With building and storm protection regulation changes, the business struggled by the late 1990s and eventually closed in the early 2000s.

Today the building houses SunRay, an outdoor patio furniture store which sells among other items, brightly colored patio furniture for lovers of island life.

Corrine O’Brien, Chief Operating Officer and Technology Officer, and employee Marilyn Reyes are both fascinated by the history of the building where they work.

The company was intent on preserving the integrity of building features that hailed backward to the structure’s original use.

“In our showroom, we haven’t really touched anything,” explains O’Brien. “We washed out the building so it would be very clean, but left remnants of the original paint on the walls untouched.”

“In our showroom, we haven’t really touched anything,” explains O’Brien. “We washed out the building so it would be very clean, but left remnants of the original paint on the walls untouched.”

Portions of the interior brick walls are bare, but most retain the colors added by previous businesses.

Large timber braces and steel beams support the ceiling and catwalks with chain railings that provided access for maintenance to the upper portions of the railcars that were once stored there. They sit above the showroom floors.

Reyes is the in-house historian of sorts for the building and has a deep appreciation of its history. She often ponders about the many people who entered the building over a century ago.

She points out how the company has left all of the catwalks intact and repurposed them for merchandise storage. She also notes the series of steel pipe sections protruding from the walls that would have provided support for shelving for the railway maintenance crew.

Remarkably, the original tracks for the streetcars are still visible in the cement flooring in two of the rooms. The tracks run from the Broadway side to the rear of the building, hinting that the cars would enter on one side, and exit the other.

When part of the space was up for lease to a prospective client of the owner, an original interior brick wall was torn down, much to Reyes’ dismay.

Reyes saved a few of the Corsicana-made bricks for posterity before they were taken away. She keeps them on display at the store. A few are still connected with an early-day version of cement.

“It’s a unique building and very well-made,” observes O’Brien. “It has lasted this long so it should last for years to come.”

Today, visitors can enter the SunRay building and appreciate the past, while making plans to create beautiful spaces for their own homes.