This feature originally ran in the May 2016 issue of Galveston Monthly.

Galveston Island is rich with history — The

Strand, the 1892 Bishop’s Palace, hundreds of examples of meticulously restored

Victorian architecture — and one relic that has been all but lost to the sands

of time. An authentic horse-drawn American LaFrance Metropolitan steam fire engine that served

Galveston for almost a half century is the latest addition to the Galveston

County Museum’s growing collection of artifacts.

Considered at the

time to be the epitome of late-18th century firefighting technology,

the roots of American LaFrance, one of the oldest and

most storied names in fire trucks, can be traced back more than 180 years.

Considered at the

time to be the epitome of late-18th century firefighting technology,

the roots of American LaFrance, one of the oldest and

most storied names in fire trucks, can be traced back more than 180 years.

“I was so excited. I could not believe such an amazing

artifact was intact and still in Galveston,” says Jennifer

Wycoff, director-curator of the Galveston

County Museum.

“The old steamer is still in very good condition, considering all the events it

has been through. It does need clean up and some restoration, in particularly

in some of the lower metal components. The wheels and wood are in fantastic

condition and still have the original red and gold paint detailing on them.”

Before restoration work begins, the public will have a chance to view

the steam pumper at the old Galveston County Courthouse, the new

home of the Galveston

County Museum.

The steam pumper, which is owned by the Galveston Professional

Firefighters Association Local 571, might never have made it to the museum had

it not been for the curiosity of historian and author Melanie Wiggins.

Wiggins, who is also a member of the Galveston County Historical Commission and the

Texas Gulf Historical Society, first learned of

the steam pumper several years ago while doing research for her book entitled Torpedoes in the

Gulf: Galveston

and the U-Boats, 1942-1943.

During World War II, the antique steel, copper, and brass steam pumper

was nearly melted down as part of the “harvesting a bumper crop for Uncle Sam”

scrap metal drive effort to build airplanes, tanks, and weapons, Wiggins says.

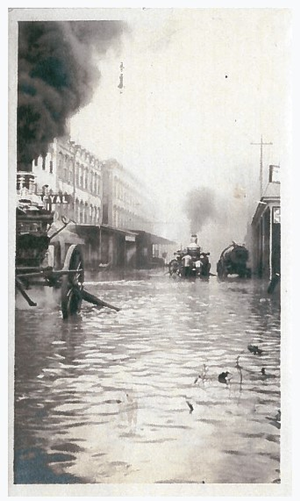

“But it was spared, thanks to public outcry,” Wiggins says. “Like Galveston itself, the steam pumper survived hurricanes,

floods, and even war, and now it will have a permanent home in the new Galveston County Museum,

which is just wonderful.”

“But it was spared, thanks to public outcry,” Wiggins says. “Like Galveston itself, the steam pumper survived hurricanes,

floods, and even war, and now it will have a permanent home in the new Galveston County Museum,

which is just wonderful.”

At the time when she first learned of it, Wiggins discovered that the

steam pumper was on display at The Galveston Railroad Museum, and she went to

see it.

“I

was amazed to see the real thing: large, ponderous, red, and with a big black

water tank and steam chimney. An impressive machine.”

In 2008, Hurricane Ike slammed into Galveston and flooded the museum with eight

feet of water — but the steam engine was spared. The museum closed for

repairs, and the

steam pumper was moved to Galveston Fire Station 1 which serves the downtown

area including the Strand Historic District and the central portion of the Port of Galveston.

Last year,

the firefighter’s union began talks with the Fire Museum of Texas in Beaumont to

find the antique a permanent home, and the steam pumper was temporarily moved

to a storage unit on the west end of the island that belonged to

firefighter Joshua Norregaard.

When Wiggins began research on her current project on Galveston fires, that’s where she found

it — and she sent up a smoke signal to Wycoff.

“I just thought she should know because we needed to find a way to keep

this Galveston

treasure on the island,” Wiggins says. “Jennifer was as excited as I was, as we

knew that it would be a major addition to the collection and fun for all to

see, as well as offering the local firemen a chance to participate in its

history.”

Within minutes of Wiggins’ call, Wycoff received a call from Galveston

Fire Department Captain Gregg Riley, who wanted to discuss the potential for

using the steam engine as a feature for a museum exhibit. Wycoff was thrilled.

On February 11, the museum curator got her first look at the horse-drawn

steam pumper, “and it was love at first sight. I asked them how I could acquire

the artifact for the Galveston

County Museum

and protect it in perpetuity.”

Wycoff says Riley instructed her to write a proposal and plans for the

artifact on behalf of the museum, and “he promised to arrange a meeting of the

Fireman’s Union and present the idea.” He

followed through on that promise.

“We quickly and unanimously voted to keep the steamer on the island,

where it belongs,” Riley says. “The Galveston Professional Firefighters

Association Local 571 owns the steamer, and we are partnered with the Galveston County Historical

Commission to allow them to restore and display

the steamer for 30 years, which I believe was the term.”

The steamer will require a major facelift, as well as structural repair

in the boiler mechanism, and some fabrication of a new brass cap on the boiler

box, he says. The restoration will be funded by donations and grants.

The steamer will require a major facelift, as well as structural repair

in the boiler mechanism, and some fabrication of a new brass cap on the boiler

box, he says. The restoration will be funded by donations and grants.

But the first step was to move

the steam fire wagon, which is not operational, from the storage unit to a

county facility.

“I

was very concerned about moving the 8,000-pound steamer, with had no immediate

funds at hand, so I proceeded to contact our county fleet director, Mike Tubbs,

who suggested Marty’s Towing LLC and promised he would assist in pleading the

cause,” she says. “Marty’s specializes in the moving of antiquities, and they

honorably agreed to donate the transportation of the fire steamer to the county

facilities.”

On March 2, Wycoff arrived at Norregaard’s storage unit, and a crowd began to

form as the mammoth machine was rolled out of the unit.

“First one man appeared, then a second, then a third, fourth, fifth,

sixth, and so on, until there was a large crowd of men circling the fire

steamer in awe of what they saw,” Wycoff says. “Many of these good men gave me

their business cards and offered to assist in restoration of the artifact, as

they were also truly amazed at its rarity.”

Wycoff says the county is accepting donations toward the restoration

effort. The idea, she says, is to keep the antique looking like just that—an

antique.

“For restoration donations, people would contact me here at the museum

and all funds would go into an earmarked account within the Galveston County

Historic Commission, for the restoration process,” Wycoff says.

“In speaking with the Galveston County Historic Commission, everyone

seems to feel the same as I do about keeping it as close to its original state

as possible, although conserve it—replace brass, stop as much rust as possible

and re-stain red colors, without using harsh paints.”

Captain Riley says he wants museum visitors to see what he sees when he

looks at the steam pumper—a glimpse of Galveston

past. “For me, looking at it makes me imagine what it must have been like to be

in downtown Galveston in the early 1900s, with

horses everywhere, wooden streets, high curbs, cotton bales, the smell of horse

manure and coffee roasters and just the major hustle and bustle that Galveston was during that

time.”

By today’s standards, the horse-drawn apparatus seems ill-equipped to

fight a raging inferno. But it was leaps and bounds better than what had come

before it. Riley confirms that this machine was state-of-the-art.

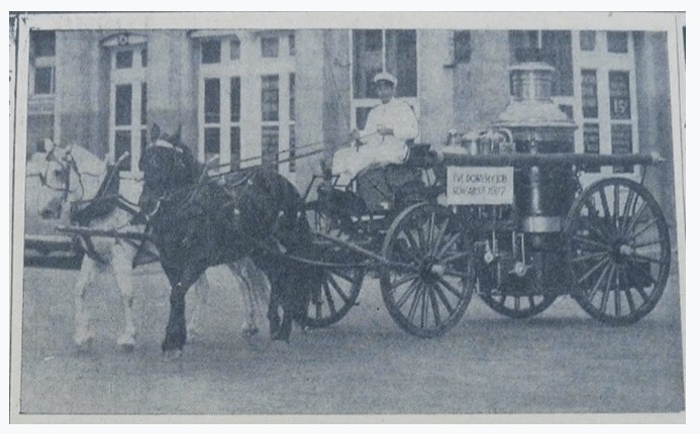

“It resembles a large wagon like apparatus, with an iron frame, a

two-person seat up front, and long wooden yoke. The large brass dome on top of

the boiler sets off the steamer in great style,” Riley says.

“The back of the steamer features a small ledge for the fireman—literal

in this sense—to ride next to the coal tray. A fire had to be started in just a

few minutes while underway and then it had to be hot enough to add coal to get

the boiler producing a head of steam, which drove the pistons that turned the

water pump. I could imagine what one of these sounded like while it was

pumping. The wheels are very tall, made of (I would guess) cypress, and steel

rimmed. Certainly, an American LaFrance Metropolitan steamer was the cutting

edge of equipment in those days.”

When the era of the horse-drawn steam fire

engine ended, some of the horses used to pull the steam pumper went on to pull

milk wagons. “There are stories of old fire horses hearing the bells clang and

taking off toward the fire, shattering all the glass milk bottles as it ran,”

Riley says. “That must have been a real sight. Once a fireman, always a

fireman.”

Norregaard says knowing that the museum will give it a forever home, “is

exactly what we’d hoped for. Just being able to keep it from leaving the island

is a really cool. It’s a piece of history, and now it gets to stay here,” Norregaard says.

“Being a small part in making that happen is a nice feeling.”

Riley agrees. “This was the best move for the steamer, as it takes real

resources and space to accomplish the restoration and the museum is the perfect

for it to be seen by the most number of people,” he says.

“I keep thinking of how things that were practical in the past are still

held in tradition today. An old captain pointed out to me that we are only

three generations removed from horses. His captain, while he was a rookie,

always urged him to ‘get it while it’s hot’ when it came to chores or any task.

Come to find out, when that old head was a rookie, his captain at the time came

in the job when horses were still in use, and the best time to scoop the manure

was when it was still hot. We have the ramp in front of firehouses today

because the horses needed a little head start to get going. The firemen had to

push the apparatus back into the station up that same ramp though, and I could

imagine that would be a job. The fire pole and spiral staircases were to keep

the horses from climbing the stairs to the living quarters.”

The more things change, he says, “the more things stay the same.”