Amid the controversy this past August concerning a certain statue that stands in front of the 1966 Galveston County Courthouse on 21st Street, another historical discrepancy came to light albeit significantly less contentious. “I kept hearing everyone refer to the location as ‘courthouse square,’” says Mike Doherty, President of the Rosenberg Library. “And I would think, ‘No, that’s Central Park.’”

Indeed, it is. However, when compared to the penultimate version, its present incarnation is markedly wanting which perhaps explains why it is no longer recognized as the respite it once was. The park has been long overshadowed by a mid-century monstrosity and an aesthetic that did not age well at all. (A lot of great things happened in the 1960s—architectural design was not one of them.)

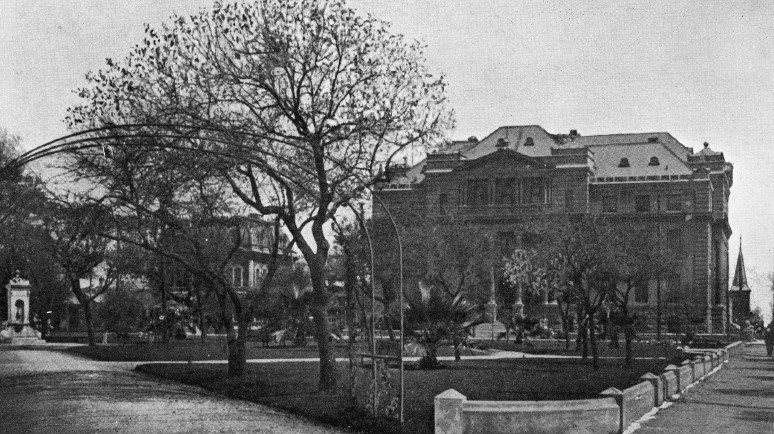

Encompassing the entire block between 20th, 21st, Ball, and Winnie Streets, Central Park was formerly a lush, beautifully landscaped oasis in the middle of downtown replete with comfortable wooden benches and one of the famous Rosenberg Fountains. Between the oleanders and live oaks, picturesque swaths of green grass covered almost the entire block, interrupted only briefly by four walking paths that radiated from a circle at the center of the park to each corner. Composition aside, the forfeiture of Central Park’s historical significance is an even greater loss and one that begs to be corrected.

‘Father of Galveston’ Michel Branamour Menard and several of his business associates purchased 4,605 acres on the eastern portion of Galveston Island from the newly formed Republic of Texas in 1836. In 1839 and 1841 respectively, the Congress of the Republic officially chartered the City of Galveston and passed an Act of Congress incorporating the Galveston City Company. The Company was formed by Menard and his fellow investors, not only to recoup more of their initial investment than was recovered from the sale of city lots but also to efficiently and proportionately develop the city.

The Galveston City Company was, “from its origin, liberal in its donations for all public and benevolent purposes,” according to an early city directory. In addition to laying out the city streets and alleyways in an orderly grid fashion, three separate sites were designated for public markets, one entire block was allocated for a college, three blocks were given to establish a female seminary, and every Christian denomination was given a valuable site for their church.

Along the central corridor of the city’s grid, every tenth block was set aside for a public square. Three of these blocks appeared on the original 1836 survey of the city, one of which was selected specifically to commemorate the war for the Republic.

On April 19, 1836, a mere two days before the decisive Battle of San Jacinto, the president of the provisional Texas republic and his cabinet were on the run, trying desperately to evade the Mexican army. They managed to secure a vessel to carry them across the bay to Galveston Island. The weary group landed on the harborside of the island near the foot of present-day 24th Street and traveled about half a mile inland to set up camp.

When Menard was planning the city, he hired John D. Groesbeck as the first city engineer. Among his first directives were to establish a pier for the Texas Navy at the foot of 24th Street and a public square on the old camping grounds later named Central Park.

Groesbeck’s successor William Harrison Sandusky laid out the center circle and connecting pathways of the park. He also designated a campfire site on the southeastern corner, but the park remained otherwise unimproved for almost forty years.

The park’s location was among the lower points of elevation in the city during this time. It was easily flooded to a depth 6-12 inches whenever it rained, and the water would often linger for weeks, further diminishing its viability for everyday use.

The park was, however, still used for political rallies, outdoor concerts, and traveling circuses, the first of which was John Robinson’s Circus in 1857. When political meetings were held in the park, attendees would illuminate the square with burning tar barrels.

One of the largest and most famous rallies at Central Park was held amid the volatile Coke-Davis controversy of 1873, when a coup to replace Republican incumbent Edmund Davis resulted in an election held before the official expiration of Davis’ term. The result, a conclusive victory for Richard Coke with a near 2:1 margin, was denounced by the state court, but the Democrats were unmoved by this decision.

Somehow, they acquired the keys to the second floor of the Capitol and took control of the building and the governorship, inaugurating Coke on January 15, 1874. After unsuccessfully petitioning President Ulysses S. Grant for military assistance, Davis finally resigned on January 19.

Following this spectacle, improvements on the park at last began to materialize in the mid-1870s. A wooden fence was built around the perimeter, the diagonal walkways from the corners to center were more permanently established, and a few trees and oleander shrubs were planted. The elevation of the park was also slowly but inexpensively raised by dumping the street sweepings there.

In the 1890s, the fence was replaced with brick curbing, and the official name of Central Park was adopted by the city, having previously referred to it informally as City Park. In 1898, it was crowned with one of the largest of 17 water fountains bequeathed by the estate of Henry Rosenberg to the city “for every man, woman, and beast.” The costly and ornate fountain was placed at the center of the park.

During the 1900 Storm, the trees and oleanders were badly damaged as they were throughout the whole of Galveston, a problem that was exacerbated by the sandy, saltwater fill used to elevate a large portion of the island during the grade-raising (1904-1911). A local group called the Women’s Health Protective Association (WHPA) assumed the task of beautifying the island by planting thousands of trees and oleanders, many of which are still thriving today.

Central Park was all but abandoned for several years after the storm, but it became one of the WHPA’s first beautification projects since it was located outside the grade-raising districts and would not be affected. In 1906, the park’s greenery was splendidly restored by the WHPA to a level that far exceeded its previous appearance.

Central Park became one of the most beautiful blocks in the city, situated between the stunning 1899 Galveston County Courthouse to the east across 20th Street (demolished), and the opulence of the original Ball High School to the west.

For decades, the majesty of Central Park anchored the southern half of downtown Galveston with a surreal, scenic display of lavish grandeur that rivaled that of many major cities. Also functional, it was used as a recess area for Ball High and the training ground for the school’s ROTC program.

Later, when the Galveston Playground Association was founded to implement a playground system for the city, they included Central Park in their efforts and outfitted a portion of it with playground equipment. Lights were installed in 1911, and the late C.C. Adamas gifted funds through his will for the addition of a public restroom.

In 1953, Central Park became the subject of a local debate that foreshadowed its eventual demise. Galveston had since lost sway to Houston as the premiere port of Texas, and the crux of the local economy had shifted from industry to entertainment.

Downtown was still thriving, but the sailors from international vessels were replaced with shoppers from Houston, the tradesmen and traveling businessmen supplemented by those seeking elevated entertainment and adventure. Thus, parking became a problem, and the idea was proposed to cement over Central Park and turn it into a parking lot.

One of the most vocal opponents of this suggestion was Edmond R. Cheeseborough who had served the city brilliantly in numerous capacities including that of Secretary of the Grade-Raising Board. His efforts were a prominent reason why the parking lot proposition did not pass, because he was the first to refer back to the indisputable verbiage of the city’s founding documents.

Over and above designating the specific blocks that would become Central Park, Michel B. Menard went a step further and transferred ownership of the land from the Galveston City Company to the City of Galveston municipality. Dated September 22, 1846 and filed November 17, the gift deed was signed by Menard as well as his City Company associate and fellow organizer Gail Borden, Jr., the inventor of condensed milk and founder of Borden Dairy.

The stipulations of the gift were explicitly outlined in the deed and addressed to the current mayor and alderman, as well as their successors. The lots were “TO HAVE AND TO HOLD…for the public use and benefit of the Inhabitants of the City of Galveston for municipal purposes, to wit: public squares forever.”

“Not only is the attempt to destroy Central Park utterly unwarranted, but it is clearly illegal,” Cheeseborough wrote in the Galveston Daily News, his words emphasized by an authority derived from countless years of public service. He went on to quote R. Waverly Smith, the author and creator of the commission style of city government adopted by Galveston after the 1900 Storm. “‘The people alone by their votes can change the purposes and uses of Central Park.’”

City commissioners promptly dropped the issue as Cheeseborough’s voice was strengthened by the vehement dissent of other residents, but the matter of Central Park was resurrected eight years later in 1961 during the aftermath of Hurricane Carla. By this time, the Galveston City Company was defunct and approaching liquidation.

“I began my career in 1969 in the Trust Department of the Hutchings-Sealy National Bank,” Mike Doherty explains. “In discussing the various trust accounts with Robert K. Hutchings, the subject of the account for Galveston City Company in liquidation came up. He explained to me that…the bank as trustee of the City Company was approached about a new courthouse being built on the site of Central Park, as the old courthouse was damaged in the hurricane,” he remembers. “At the time, the park was surrounded on all four sides by streets, the older courthouse being across 20th Street from Central Park.”

On the basis of the original deed, the City Company declined the county’s request, but in 1962, the city reached an agreement with the county. On Friday, February 8, 1963, Galveston County officially became the owners of Central Park by a vote of the city.

Two deeds were filed. One passed the property from the City of Galveston back to the City Company via their Hutchings-Sealy trustees, and the other transferred the park from the bank to the county. The deeds gave the county a site for their new courthouse for a consideration of $1, on the condition that Central Park be retained for use by the public.

Since the damaged courthouse was still being used out of necessity, the new courthouse was erected on the 20th Street and adjacent sidewalk easements and a bit into the park, after which the old building was demolished and the land used for an annex at the rear of the courthouse.

That building still stands today on 21st Street, along with a park that is a mere shadow of its former glory. However, although the grandeur is gone, let Galveston always remember that this space forever belongs to the people, and it should therefore be a place that forever represents all residents.