“Kimber, I heard your interview on KPFT this week and have always had a huge interest in the Maceo family. Since you have written so much on Galveston history, I was curious if you knew anything about the Galveston City Stock company that was issued soon after Texas won its independence. My wife restores furniture and we found two Galveston City Stock certificates in an old desk she bought. I started doing some research and it’s an incredible story…I have been sitting on these two stock certificates for a few years and after I heard your interview, I was hoping you would know more…Best, David Davitte.”

“Fate had me listening to KPFT in the car that day,” says David Davitte. And thus begins a tale that only seems possible in Galveston—the city with a history so dynamic and alive that it can travel hundreds of miles and sit buried for nearly two centuries, waiting patiently to reveal itself to precisely the right person at precisely the right time.

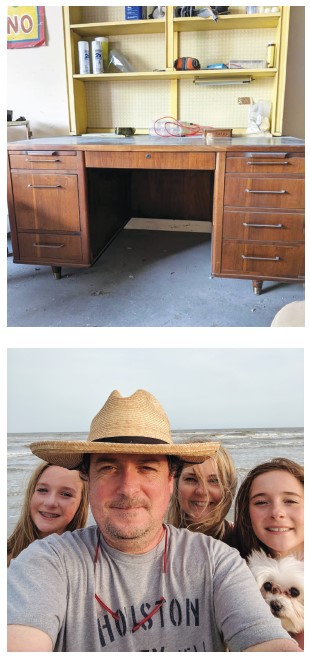

Originally from Fort Worth, David Davitte moved to Houston in the early 1980s and there met his future wife Beth, a native of Uvalde. The couple lives in Memorial City with their two teenage daughters, and Beth has been a rescuer and restorer of vintage furniture for fifteen years.

“We’ve found socks and shorts and just—junk,” she laughs. “And we’ve found some old pictures and cards and stuff, but we’ve never come across anything quite like this before.”

Beth purchases furniture primarily from auctions and estate sales, although she cannot quite remember where exactly she located the desk in which they later discovered several original documents from the 19th century.

“It’s a really cool desk. It’s kind of a vintage desk and it was probably in somebody’s office. It could have been a law firm,” she describes.

“You can tell it’s old by the hardware, and it has the old pull-out writing tablets on the side and a lock on the drawer. We’ve had a few [desks like these] before; they usually go for pretty high-end. And I paint a lot of the items I find because they are usually beat up or old, but this is definitely one that I would not paint.”

“You can tell it’s old by the hardware, and it has the old pull-out writing tablets on the side and a lock on the drawer. We’ve had a few [desks like these] before; they usually go for pretty high-end. And I paint a lot of the items I find because they are usually beat up or old, but this is definitely one that I would not paint.”

“It was one of those projects that was stuck to the side,” David explains. “Then one day we took the drawers out, and there was an envelope in the back, and it said “very important papers” on it. I said to one of the guys I was with, ‘I betcha it’s some stock certificates.’ I was kidding around, but we opened it up and sure enough, that’s what was in the envelope.”

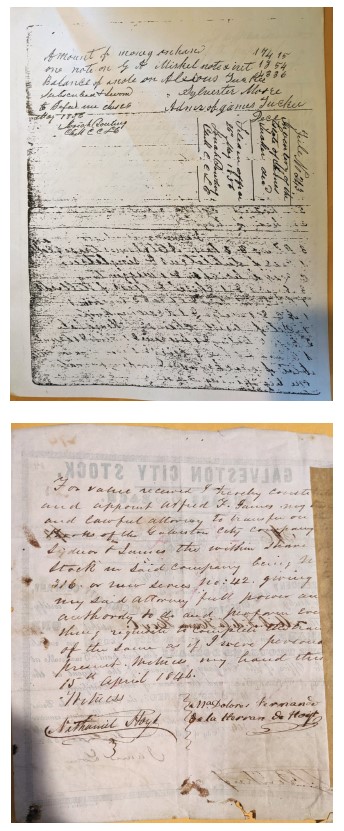

“There was actually a will in there, as well,” he adds. “I’d love to get the original people back in touch with this.” The will is a photocopy of an original document dated May 26, 1856, that lists “A just and true inventory (and appraisement) of the personal property papers and money [of the] Estate of James Tucker deceased that came to our knowledge.”

Named assets include various livestock and notes of owed interest, along with $174 in cash. Attached to the will is a genealogy worksheet of a woman named Frankie Olive Smith Hickey Hansel.

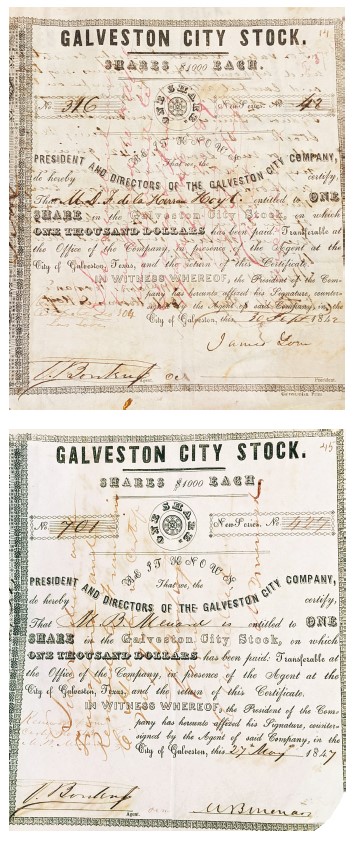

But the stock certificates were what most intrigued David. Unlike the will, the stock certificates are original documents dated 1842 and 1847.

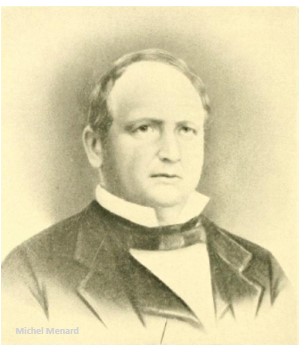

“I went down a rabbit hole for about four days on this,” he remembers. “You kind of know some of the names, but you don’t know the history behind it, like Menard, and just the fact that one of the certificates has his name on it. I was fascinated by his story. He only lived 51 years, and he did a lot of stuff in 51 years.”

Most Galvestonians and Texas History enthusiasts recognize instantly the surname of Michel Branamour Menard, signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence and the Father of Galveston. And it is not merely his name that rests upon the recovered documents but his original signature, along with those of Gail Borden Jr. and James Love. One of these is still today a household name, and both were instrumental in the establishment and development of Galveston Island and the State of Texas.

Michel B. Menard (1805-1856) was born near Montreal, Quebec, and began his career as a fur trader at the age of 15. Despite being illiterate, he quickly climbed the ranks of the Detroit-based American Fur Company but left in 1822 to work with his uncle in the fur trade at Kaskaskia, an indigenous tribe in Illinois. During this time, he learned to read and write both French and English.

Over the next decade, Menard worked his way southward through Missouri and the Arkansas Territory before migrating to Texas where he continued his trade, collecting skins and furs from the Shawnee and exchanging them for livestock and permits to locate land. (Location surveys differed from boundary surveys, showing improvements and advantageous topography within the previously surveyed boundaries. This work was often paid for with titles to portions of the land.)

By 1834, Menard not yet 30 years old owned tracts of land from the Trinity River to Liberty totaling 40,000 acres.

Menard most likely discovered Galveston Island around 1833 when he opened a trading post on the newly minted Menard’s Creek off the banks of the Trinity. Galveston was likewise a Mexican trading post at the time, but the only developments were a few poorly built shacks, some gambling houses, and a large population of Mexican prison laborers living in disastrously squalid conditions.

By 1834, Menard not yet 30 years old owned tracts of land from the Trinity River to Liberty totaling 40,000 acres.

Menard most likely discovered Galveston Island around 1833 when he opened a trading post on the newly minted Menard’s Creek off the banks of the Trinity. Galveston was likewise a Mexican trading post at the time, but the only developments were a few poorly built shacks, some gambling houses, and a large population of Mexican prison laborers living in disastrously squalid conditions.

Despite its rugged appearance, Menard envisioned a bustling seaport on the island, a boon of commerce and model of efficiency. He had no legal claim to the land, no foreseeable avenues to realize his ideas, and yet Menard found this vision of a grand seaside city unshakable. It became his life’s work.

Since Texas was still part of Mexico and the island was yet unclaimed, the first obstacle for Menard was the requirement to swear an oath to the Mexican government and proceed on a path to Mexican citizenship in order to obtain a land grant. He sidestepped these by forming an alliance with Juan Seguin, the famed ally of Texas independence and later the only Mexican Texan in the Republic of Texas Senate.

Under a new law passed in 1830, Juan Seguin was entitled to a land grant as a citizen of Coahuila and Texas, his recognized defense of Mexico against “Indians” fulfilling one of the other necessary requirements. He selected one league and one labor (about 4605 acres) located on the eastern portion of Galveston Island.

His grant was confirmed on April 27, 1833, and Seguin hired Menard as his agent to locate the land. Although the exact details of the transaction are unknown, Menard received the title for the land shortly afterward in 1834.

Menard then had the first official survey of Galveston produced by Isaac N. Moreland. His field notes, written in Spanish, refer to “San Luis Island” and were filed in Liberty on July 8, 1834.

Then in 1835, John P. Borden resurveyed the land for Menard. His notes mention a church, custom house, “rich prairie,” “cypress trees,” and “hills of white sand.”

John’s brother Gail Jr. had been a surveyor for Stephen F. Austin’s colony and regularly assumed the duties of his colonial secretary when Samuel May Williams was away. Williams was also a colleague of Menard’s; he and Thomas F. McKinney worked with him at the Trinity trading post. All three of these men would later become cofounders of the Galveston City Company.

Unfortunately, around the time of the second survey, Menard’s real estate ambitions were halted as fervor grew around the revolution movement. An avid supporter of independence, Menard was at Washington-on-the-Brazos and signed the Texas Declaration of Independence. Juan Seguin served at the Alamo but was sent for reinforcements a few days before the massacre.

Prior to the first session of the Congress of the Republic of Texas in 1836, Menard sent a petition to have his Mexican land grant confirmed under the new government, his efforts to organize Galveston having been significantly delayed until a stable government was formed. Future investors were uninclined to purchase if the validity of their land titles could be questioned.

Menard explained in the petition that he had portioned the land into ten interests, nine of which were sold and the tenth reserved for himself. He also attested that the land had been divided into town lots for some time, and that its organization and efficiency, with evenly plotted and symmetrical blocks atop a grid system, provided the basis for immediate development and improvement.

“It will add to the value of the coast lands, and to the revenue of the country; and the arrangement will give food and clothing to a suffering and gallant army.”

The “arrangement” stipulated that Menard would pay the Texas government $50,000 in clothing and provisions for the Texas Army; $30,000 payable immediately and the remainder within two months. Texas also required that some 15 acres on the far eastern portion of the island (all the land that was at the time east of 7th Street, the far eastern border of the original town plat) be reserved for “governmental fortifications.”

Additionally, one city block bordered by Avenue A (present-day Harborside Dr.), Strand, 23rd, and 24th Streets would be reserved for a customs house. These parcels were owned by the Republic for several years but were eventually sold to private citizens.

Additionally, one city block bordered by Avenue A (present-day Harborside Dr.), Strand, 23rd, and 24th Streets would be reserved for a customs house. These parcels were owned by the Republic for several years but were eventually sold to private citizens.

On December 10, 1836, the Texas Congress officially deeded the title of Galveston to Michel Menard and his nine associates, Dr. Levi Jones, Mosely Baker, Thomas Green, Samuel M. Williams, William R. Johnson, Thomas T. McKinney, William Hardin, John R. Allen, and Gail Borden Jr. Together, these men organized a stock company, and the Galveston City Company held its first organizational meeting on April 17, 1838.

Unlike “company towns,” which were in essence a 19th century experiment in small-scale social tyranny, a city company issued stock for purchase to initiate the development of new cities. Company towns were typically built around one certain industry or corporation to exploit and control employees, but a city company existed primarily on paper.

The Galveston City Company named a board of five directors at their first meeting. Among the directors was James Love, a former U.S. Representative for Kentucky and bitter rival of Sam Houston. In 1845, he was elected to represent Galveston County at the annexation convention where the Texas Constitution was written.

On April 20, 1838, the Galveston City Company issued 1,000 shares of stock through a board of trustees at an estimated nominal value of $1,000 per share. Prior to the public sale, the board put out a call for bids for construction along the wharf front, an area with its own dramatic history that continues today, and a number of parcels were donated by various members to individuals and organizations, requiring immediate improvement as the only caveat. Furthermore, every tenth parcel was set aside for the establishment of public parks.

The Company also hired John Groesbeck in 1838 to produce another survey that became the well-ordered system of letters and numbers still used today. Broadway Avenue and 25th (or Bath Street) were original to the 1835 map, but other streets were identified by well-known names like San Jacinto, Menard, and Christy, as well animals, mythological figures, and geographical locations.

Groesbeck altered these to a format that placed numbered streets from east to west and lettered streets from north to south, and Buffalo Street became Avenue P½.

The City Company’s claim reached to 57th Street, but city proper extended roughly only to 33rd Street and Avenue M. Only outlots existed beyond these borders in the early days. Thusly, Groesbeck drew some of these outlouts as large as four times the size of the regular city blocks, and soon they had to be subdivided.

South of Avenue M, the blocks were split up and given the “half” street designations used today. East of 33rd Street, the half streets were originally alleyways.

South of Avenue M, the blocks were split up and given the “half” street designations used today. East of 33rd Street, the half streets were originally alleyways.

Despite the exacting order of their perfectly laid plans and streets, the Galveston City Company would not become solvent for nearly two decades. When the stock was first issued on April 20, 1838, it was below par and continued to decline until it was worth only 10 cents on the dollar. The Company in turn allowed land to be purchased with their shares, which became a common practice since the shares were worth infinitely more in land than in dollars.

The City Company officially organized the municipality of the City of Galveston in 1839 and incorporated themselves in 1841, but real estate in Galveston remained all but worthless from 1840-50.

Still, the company worked tirelessly to increase the value of their holdings, even sacrificing their own land and capital for municipal improvements. On September 2, 1856, Michel B. Menard passed away, less than a month before the stock of Galveston City Company reached par.

For more than 70 years, the Galveston City Company controlled the growth and planning of the island. Shares continued to climb in value, eventually making the original owners incredibly wealthy.

Often these men would manipulate local politics to achieve their ends, but the result was a determinate, ordered growth of a well-organized, philanthropic, and community-minded city. Unfortunately, this fostered sense of control by a select few eventually led to the Company’s end.

In 1909, H.A. Landes was President, and the company still had some valuable remnants of property with only a few shares outstanding. On April 18, however, the scheming of the famed and mysterious Galveston icon Maco Stewart dissolved the Galveston City Company.

At a board meeting held that day, Stewart was elected President and then proceeded to purchase the last remaining assets of the company for $10,000. With this simple act, the company was liquidated and passed out of existence.

Fortunately, the work of the founders and their well-thought plans remain, as does the desk that brought their incredible story to light once more. “We still have it at the warehouse,” says Beth Davitte. “It’s against the wall and I actually sit there and eat lunch and return client’s emails.”

Many of our stories such as this one start as suggestions from our readers. If you have an idea for a story for possible inclusion in an upcoming issue of our magazine, please email us a short description to info@galvestonmonthly.com. Please keep your idea brief and be sure to include the names and contact information that are important for the story. While we cannot guarantee a response, we look forward to reading your idea and hopefully including it in our publication.