Along the eastern edge of Bolivar Peninsula, just past the point where Highway 87 ends and veers left into Highway 124 towards I-10, sits the unincorporated community of High Island--which is not really an island at all. This brief coastal expanse is attached to the mainland, but it is located atop a salt dome that gives it an elevation

of 38 feet, the highest elevation on the Gulf Coast between Mobile, Alabama, and the Yucatan Peninsula.

Primarily

known today as a birdwatcher’s paradise, High Island experienced a brief run of infamy in the national news during

the 1970s.

Serial killer Dean Corll and his accomplices buried several of their victims at the High Island beach, six of which

were recovered throughout the decade. Then in 1978, a story surfaced that Texas’ most famous rhinestone

-

studded cowboy Rex Cauble had used High Island as a base for a marijuana smuggling operation that became one

of the largest in U.S. history.

Years later, the saga ended with the largest forfeiture of attachable assets ever recorded, but left behind a

lingering uncertainty among Texans...Did he, or didn’t he?

Charles “Muscles” Foster was nothing like his boss, but he sure wanted to be. A churlish, un

mposing man, Foster

was 5’5” and 155 pounds, and his shoulders hunched under the weight of his insecurities.

He was totally woman

-

crazy

—

not in the “love you and leave you” way, but rather the desperate, yearning,

pathetic kind of crazy which often left

him heartbroken and broke. Foster was a hard worker, though, and

tenacious, despite his physical and emotional shortcomings. He was also magnificently gifted with horses.

Halfway through his 7

th

grade year, Charles dropped out of school to become a ranc

h hand. He was soon given a

nickname as a joke by his fellow hands after they watched him struggle to move a small bale of hay. It stuck. But

instead of feeling slighted, Muscles wore his nickname like a badge of honor while working in rodeos and breaking

horses to earn extra income.

Word of his talents began to spread among the ranching and rodeo communities, and his services were soon

courted by one of the wealthiest men in Texas, Rex Cauble. Foster’s god

-

like reverence of Cauble (and his money)

formed

the basis of their long, working relationship, but each held an ample amount of genuine affection for the

other. Cauble was known to be simultaneously infuriated by Muscles’ ineptitude and soothed by his undying

loyalty

—

both of which would eventually lead

to his own undoing.

Word of his talents began to spread among the ranching and rodeo communities, and his services were soon

courted by one of the wealthiest men in Texas, Rex Cauble. Foster’s god

-

like reverence of Cauble (and his money)

formed

the basis of their long, working relationship, but each held an ample amount of genuine affection for the

other. Cauble was known to be simultaneously infuriated by Muscles’ ineptitude and soothed by his undying

loyalty

—

both of which would eventually lead

to his own undoing.

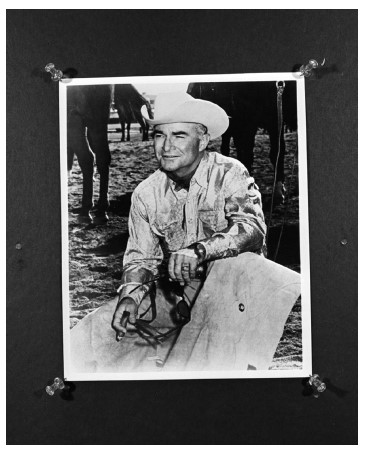

Like Muscles, Rex began his career early, as a 15

-

year

-

old roughneck on the oilfields of East Texas. Unlike Muscles,

he was good

-

looking and charming, tanned and muscular from his grueling work.

After years of toiling in the fiel

ds, Cauble secured his own equipment and enjoyed modest success as a wildcatter.

He spent all of his earnings on clothing and accessories, lavish stays at luxury hotels, and massive bar tabs, mostly

in the interest of wooing women. Rex Cauble was determine

d to be a millionaire one day, and he was not going to

wait until then to look or act like it.

Rex’s big break did not come from striking black gold, however, but rather from marriage. When he met

Josephine Sterling, a wealthy widow whose late husband h

ad been one of the largest shareholders in Humble Oil

Company (now Exxon), Rex claimed his net worth was $2 million. A more accurate estimate places it at around

$200,000, but he believed himself, so Josephine believed him, too.

The smooth

-

talking Rex n

ot only managed to entice the monied matron into marriage but also convinced her to

give her 2

-

year

-

old adopted son his name. He also assumed complete control of Josephine’s fortune.

He did well with it, or so it seemed at first. He created the umbrella

company Cauble Enterprises, and it was

estimated to be worth between $80

-

100 million by the time Rex was forced out of his position as CEO in the late

70s. However, Josephine claimed at one point that it would have been worth $150 million if not for Rex’s

bad

business deals.

In addition to the original oil shares and speculations, Cauble Enterprises came to include a steel company, a

welding company, a horse trailer company in Fort Worth, two banks, and Rex’s coup de gras, Cutter Bill’s Western

World. D

ubbed the “Neiman Marcus of Western Wear,” Rex’s taste for the flamboyant and flashy was a perfect

sell to an oil

-

rich, new

-

monied Houston market during a decade marked by decadence. A second location was later

opened in Dallas.

The luxury western wear

store, brimming with rare, unique items and four

-

digit price tags, drew in celebrities like

Andy Warhol, Mick Jagger, and Muhammad Ali. The store was hired as a costume consultant and outfitter for the

hit 1980 drama

Urban Cowboy

set in Houston, and the ci

ty erupted when the film’s leading man John Travolta

showed up at Cutter Bill’s to shop for his personal wardrobe. Further adding to the appeal of the store was the

fame of its namesake, a real horse named Cutter Bill.

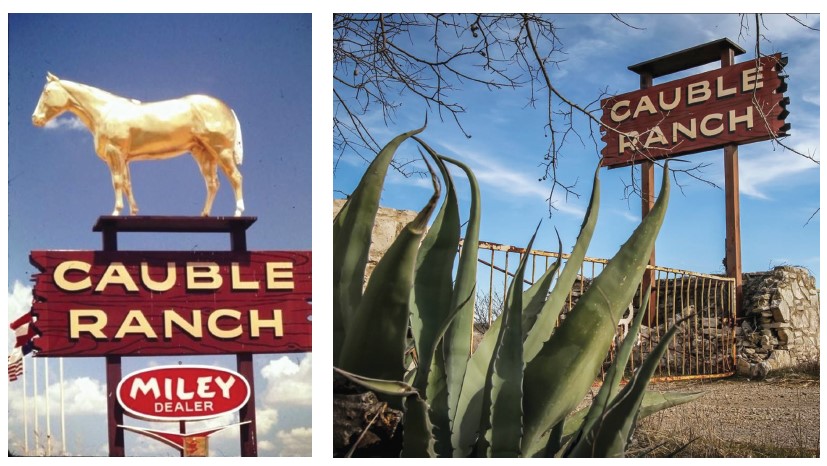

Aside from his serious business de

alings, Rex’s favorite venture was breeding quarter horses. He acquired some of

the most famous studs in the industry during the mid

-

1950s, but the famous golden palomino was purchased at

the request of his wife Josephine.

In industry speak, “cutting” i

s the ability to pick a calf out of a herd and hold it apart, and Cutter Bill was a natural.

Eventually, he became a world champion and earned Rex an estimated half a million dollars.

Cauble built a massive stable at his ranch north of Denton called the

Cutter Bill Championship Arena that included

a show ring and a trophy room. A golden statue of Bill was placed at the front entrance.

It was amid this business of horses where Rex Cauble first met Muscles Foster sometime around 1960. Cutter Bill

was on

ly four years old and starting to show signs of the champion he would become.

Muscles knew it the first time he watched him perform, inasmuch as he formed an immediate kinship with his

new employer. Rex hired him to break horses and breed mares, but Mus

cles worked his way up to caretaker of

Cutter Bill and ultimately the overseer of all the Cauble ranches.

This position granted him unfettered access to every barn, stable, airplane, and tract of land owned by Rex

Cauble, as well as the ability to tell

any foreman or ranch hand to take a week off if Muscles needed them out of

his way. His situation proved most advantageous when he was reunited with his old acquaintance Raymond

Hawkins, who introduced him to Carlos Gerdes.

An orphan and former juvenile

delinquent, Hawkins lived in Georgia and worked as a cowboy. In the early 1970s,

he met Gerdes who shared his plan to make millions by smuggling marijuana over the water from Colombia and

through Florida.

An orphan and former juvenile

delinquent, Hawkins lived in Georgia and worked as a cowboy. In the early 1970s,

he met Gerdes who shared his plan to make millions by smuggling marijuana over the water from Colombia and

through Florida.

Hawkins lured Foster to Georgia with a simple r

equest to break some horses for him, but when he arrived,

Muscles realized that the “work” was not exactly what had been promised. Fortunately, a $20,000 payday was

more than enough to assuage any frustration about his actual task

—

unloading a huge cargo of

marijuana recently

arrived from Florida.

This was Muscles’ first taste of “big money,” and for the first time, the dream of becoming a wheeler dealer like

his revered Rex was coming into focus. This was also the first time that Rex Cauble’s name showed

up on the feds’

radar.

Muscles took a company truck to his first visit to Georgia, unaware that Gerdes was being surveilled by the

Georgia Bureau of Investigation. When Muscles arrived, an agent scribbled down the number of the Texas license

plate and

later learned that it was registered to a horse trailer company owned by Cauble Enterprises.

Soon after the FBI became cognizant of these new smuggling routes, Florida seized up and ceased its appeal as a

conduit. By the time Muscles entered the picture

in 1976, Hawkins and Gerdes were already considering a new

scheme, one that suddenly came into focus when they learned of Muscles’ unbridled access to Rex’s properties

—

and his funding.

Muscles returned to Texas and told Rex that he wanted to go into th

e shrimping business. Whether it was willful

ignorance or merely a blinding familial affection for his mentee, Rex allegedly had no idea at this point that

Muscles’ sudden interest in seafood was merely because it was a great cover for dope smuggling. With

out

hesitation, Rex called a boat dealer in Aransas Pass to tell him that a Mr. Foster would be visiting him to purchase a

shrimp boat.

Transportation was secured, and once the cargo made it to land, Muscles could clear out one of Rex’s ranches

where

the loot would be divided and distributed. But the step in between was the hardest part

—

unloading the

shrimp boats in a secure, nondescript location. Muscles scoured the Texas coast and discovered a location on High

Island, population 450, situated in a re

latively undeveloped area between Galveston and Port Arthur.

Underneath a bridge that crosses the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, Muscles built a metal warehouse and affixed a

sign at the entrance

—

Thompson Seafood Company. He even called some friends and fa

mily to tell them he was in

the shrimping business, and perhaps in a half

-

hearted attempt to make his newfound fortune feel legitimate,

Muscles occasionally insisted that they bring actual seafood onto the boats.

The Thompson location was surrounded by

brackish weeds and brush that grew more than 10

-

feet tall and

rendered it practically invisible. It could not be seen from the bridge, and Muscles dredged a small inlet so that it

could not be seen from the canal, either. Admittedly, his fellow smugglers w

ere awed a bit by Muscles’

maneuvering; it allowed them to unload upwards of 35,000 pounds of marijuana at a time completely undetected.

A load that size would net Muscles and his crew nearly $5 million

—

a pound purchased in Colombia for $25 could

be sol

d for $200 in Texas. Court documents would later attest that during its brief, two

-

year span of operation

between August 1976 and December 1978, the High Island location was responsible for the influx of 172,000

pounds of marijuana into the United States,

valued at $34 million. It is still considered one of the largest drug

importation outfits in US

h

istory.

In 1978, the Cowboy Mafia

—

so dubbed by a Dallas newspaper

—

was finally busted when a raid on the incoming

Agnes Pauline

resulted in the recovery of 2

2 tons of marijuana and the arrest of multiple cowboys

-

turned

-

smuggler. For some reason, this shipment had been routed directly past the High Island location and into Port

Arthur where a slip had been rented.

If government agents had not already been al

erted to the operation and planned their sting, the apparent reek of

the boat as it pulled into the harbor would have been enough to warrant investigation. Agents careened out of

every corner of the docks as soon as the boat dropped anchor, its pungent, he

rbal odor wafting onto land as

incriminating proof of the crew’s cargo.

The federal government indicted 29 people by the time the trials began in September of 1979, with charges that

went far beyond smuggling into racketeering. Twelve of them stood trial

, others pled guilty or traded their

testimonies for leniency, and some, like Muscles, fled the country.

The collective plan of the witnesses was to direct all the blame to Muscles, but the lawyers developed a different

strategy, instead attempting to i

mplicate Rex Cauble as the mastermind. It was not a solid defense, resulting in the

conviction of nine of twelve defendants.

It did, however, set the scene for the eventual indictment of Rex, a cause that was further ingratiated by the trial

of Muscles

Foster. For a while, several of his cohorts thought him dead and even speculated that he had been

murdered by Rex, but Muscles surfaced in Bolivia soon after the trials.

Although Bolivia has a policy of not extraditing for drug charges, the DEA hired Bo

livian bounty hunters to kidnap

Muscles and deliver him to an airport where he was escorted back to American soil by a narcotics agent. His family

hired attorney G. Brockett Irwin to defend him.

Irwin quickly learned about Muscles’ long and arduous batt

le with depression and mental illness, which included

several suicide attempts, hospitalizations, and electroshock therapy, and formulated a rather outrageous strategy

for a drug trial

—

innocence by reason of insanity.

He rationalized that Muscles did no

t have the mental fortitude to organize such an operation, but rather was

lured in and morally absconded by Gerdes and Hawkins. It worked. Muscles was fully acquitted, but his purported

innocence subsequently left him unable to deflect heat from his belove

d Rex and unable to testify on his behalf.

On paper, the evidence against Rex Cauble brought forth at his 1982 trial was overwhelming. Bank records

betrayed multiple loans of tens of thousands of dollars to Muscles Foster, which were always repaid with

interest

in lump sums

—

by a guy whose salary was $250 a week.

They also indicated several large cash deposits which Rex claimed were gambling winnings and cattle sales, but no

records of those transactions could be produced. This seemed to the prosecutio

n clear evidence that Rex was the

financial backer of the operation. He lent the cowboys money to secure the cargo, reaping financial benefit from

the interest along with a substantial fee for his services.

Muscles always maintained that Rex knew nothin

g of the inner

-

workings of the operation. He said, “[Rex] never

asked me any questions about anything during the smuggling. He loaned us money and we leased his planes, but

he turned his head and went about his business.” Some historians argue that this wa

s also Rex’s only argument for

his “innocence,” the fact that he had never actually participated firsthand in a drug deal.

Refuting this assumption was a tape of a conversation between two other cowboys that seemed to solidify Rex’s

protestations, and i

nitially, it appeared enough to exonerate him.

“You know who they thinks done it is R.C. Big Man down there,” says a man named Jamie Holland. “They are

wrong,” replies Willis Butler. “Well, I know,” Jamie replies, “but they are trying to get after him.

See, they wanted

him on a bunch of other things.”

Those “other things,” however, were not necessarily criminal but merely the unfortunate byproduct of a

fabulously wealthy man who had angered a lot of powerful people with his attitude, infidelity, and f

reewheeling

style.

Indeed, during the arrest of the

Agnes Pauline

crew in Port Arthur, an agent was heard questioning one of the

men immediately upon his arrest. “Okay, cowboy,” the agent said. “Are you going to give us the big man in

Denton?”

Howeve

r, both judge and jury proved immune to the possible politics of Rex’s arrest and trial, and he was

convicted on ten counts: two violations of the newly enacted Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations

statute (RICO), one count of conspiracy to viola

te RICO, three violations of the Interstate Commerce Travel Act,

and four counts of misapplication of bank funds. He was sentenced to five years for each count, to be served

concurrently.

The financial implications of the conviction lasted much longer f

or Rex than his prison time. He did manage to

deal his way to a civil asset forfeiture that was not nearly as hefty as the government would have liked

—

around

$12 million

—

although it was still the largest in the nation’s history.

To p

rotect the remainder

of Cauble E

nterprises, Rex signed away his 31% ownership to Josephine and their son

Lewis after his conviction. Both promised that after he had served his sentence, his share of the company would be

returned to him.

Unfortunately, Rex’s relationships wi

th both Josephine and Lewis were tumultuous even before his conviction,

and five years in prison did nothing to dampen their disdain for him. Shortly before his release in 1987, they

restructured the company and renamed it J&L Partners, effectively rescind

ing their handshake deal. They granted

Rex a $7,000 monthly allowance, but this hardly provided the life of luxury to which Rex was accustomed.

Left with no options, Rex decided to divorce Josephine, an action he assumed would entitle him to at least hal

f of

his wife’s holdings. But the judged ruled that since Rex knowingly signed away his interest, he had zero claim to the

company or Josephine’s fortune. He was awarded only $39,997. According to the judge, $3 was deducted for

telling white lies.

Rex l

anguished during his last years, stringing together a few failed business ventures in desperate attempts to

return himself to his former glory. Despite his continued and unwavering declarations of innocence, he found

himself consumed by a cloud of speculat

ion and failure that followed him wherever he went.

In June of 2003, two months before his 90

th

birthday, Rex passed away

—

the guiltiest innocent man that Texas has

ever known.