Ireland native John L. Darragh (1809-1892) settled in Galveston in 1839 after living on the east coast for a short time. Probably due to his poor childhood, he focused more on business than social matters, and was known for his frugal habits.

Darragh initially established a grocery business but branched out into real estate investments where he earned his fortune. Within a year of his arrival to Galveston, Darragh was elected justice of the peace for the county and was referred to as Judge Darragh from than point on.

One of the first alderman of the city, he also purchased controlling interest of the Galveston City Company. Because of his success and major investments in the community, he was elected president of the National Bank of Texas, Galveston City Company, and Galveston Wharf Company, but acted mostly in a figurehead capacity in each.

At age 33, Darragh married 17-year-old Ellen Georgiana Charlton Harris (1825-1896) from Georgia in 1842. The couple had four children: John (1844-1916); Robert Emmet (1846-1878); Georgina (1857-1857); and Daniel (1848-1874).

Though the 6-foot tall businessman who preferred solace was not the best match for a petite, gregarious younger woman, they remained married for almost 37 years before Ellen filed for divorce in 1878. The union was marred with unkindness and the loss of three of their four children.

Their divorce became one of the most publicized cases of the year. Despite an annual income of $12,000, he only allowed his wife $45 per month for food and clothes. So much evidence was produced to prove that Darragh was both verbally and physically abusive to his wife that his lawyers did not contest the charges. On the second day of the trial, Ellen was awarded 50% of an estate valued at $200,000.

Darragh married his second wife Susan Earl (1843-1880), 34 years his junior, in 1879. He moved his new bride into a house on Winnie between 24th and 25th Streets which was previously used as an “assignation house” where fallen women and their clients could rent rooms by the hour. Darragh did not live there with her, only making occasional conjugal visits.

Susan gave birth to a son, James Lewis (1880-1905) in August 1880 but passed away from childbirth complications the following day. Her funeral was held at her mother’s home on Postoffice Street.

Laura Leonard (1856-1959) became Darragh’s third wife on June 18, 1881, in Luling Texas. Almost 50 years younger than the businessman, Leonard was the daughter of former Galveston mayor Charles H. Leonard.

Laura was moved into the same ill-reputed house where his last wife had died, and he would not publicly acknowledge the new marriage for several days. Ten months later, their son Albert Mills (1882-1943) was born, followed by his brothers Charles Leonard (1884-1943) and Frederick E. (1885-1959).

Laura was obviously patient with her unusual husband, and as a result of her influence, John Darragh purchased lots 8, 9, and part of 10 on block 435 at 15th and Postoffice around 1884. There were two existing structures on the land—one that was built by John Chapman in 1845, and the other by Charles Jordan in 1871.

A map at the Rosenberg Library shows a large, two-story residence with another two-story house offset in the rear, and three small outbuildings on the north side of the property. There is no record of the condition of these buildings which may have sustained damage in the hurricanes of 1871 and 1875. The Darraghs moved to the property in 1884 or 1885 and undertook a major renovation two years later.

Local architect Alfred Mueller (1854-1896) was hired to join the two homes to form a basis for a new, grander structure facing 15th Street. Laura supervised all of the design and contract work for the project, which cost approximately $8,000. Due to the breadth of the task, Mueller’s friend Nicholas Clayton aided with communications with some of the contractors.

Mueller established a central hall floor plan for the two-story Greek Revival structure with a five-bay, double gallery portico and six octagonal Doric columns across the east front. Each column featured a single flute.

Upon entering the front door, the sitting room and dining room on the north (or right) side were created from one of the original structures. The left side front and back parlors as well as a rear hall behind the staircase were created from the other pre-existing building. All of the first-floor rooms opened into each other with double sliding pocket doors.

A small bay window was added to the dining room, and a large one projected from the south side parlor. A quarter turn stairway with a polygonal newel post anchored the north end of the central hall, detailed with winders and turned spindles. Several additional rooms were added during the remodel, forming a rear “L.” These were most likely the kitchen and pantry on the first floor and bedrooms above.

Mueller also created one of the most distinctive features of the home, an octagonal two-story tower projecting from the northeast corner topped by a pitched “witch’s hat” roof. A stained-glass window with a peacock design was installed over the front entrance, making a stylish statement to visitors.

True to his miserly reputation, Darragh agreed to these elaborate accents in the front hallway and parlor where visitors might see them, but preferred a simpler style in the private areas of the home.

The final plan incorporated nine rooms, seven porches, five closets, five fireplaces with ornate mantles, and a square cupola topping the home with a small, hipped roof. The home’s roof was covered in four-inch lapped slate shingles. One hundred feet of seven-foot high white picket fencing lined the back of the property, and a nine-foot brick wall bordered the alleyway.

Mueller’s ongoing projects also refurbished the interior of the carriage house rooms, installed new glass windows and blinds in the stable, and repaired and moved the privy into the backyard. A new cypress-lined, 9-foot deep cesspool was incorporated as well. Even the chicken house was spruced up, moved and put on new block foundations.

The spacious rooms with 12-foot ceilings were lavishly furnished by Mrs. Darragh. Original receipts for her purchases of vases, ceramic dogs, liquor sets, etched lampshades, a music box, an inkstand, antique oak and cherry furniture, a telephone, and other items are in the collection of the Galveston and Texas History Center of Rosenberg Library. Though there were wood floors throughout the residence, she commissioned carpeting with border accents by Brussels, Wilton and Axminster to cover them.

The final feature installed at the residence was a wrought- and cast-iron fence that became its crowning glory. Designed by Mueller specifically for the home, the elaborate enclosure was 248 feet in length and had nine cast iron posts, two single gates, three double gates, and a matching cast stone post on the north brick wall.

While the home where the Darraghs would live was being created, so was their resting place. In early January 1887, renowned architect Nicholas Clayton completed a commissioned marble burial vault in Old Catholic Cemetery for the family. It was considered to be one of the most elegant creations of its kind in Galveston.

While the home where the Darraghs would live was being created, so was their resting place. In early January 1887, renowned architect Nicholas Clayton completed a commissioned marble burial vault in Old Catholic Cemetery for the family. It was considered to be one of the most elegant creations of its kind in Galveston.

During the last few months of 1888, Darragh’s behavior came into question and Laura was assigned power of attorney over his estate on November 28. Foreseeing his desire to be away from unfavorable attention, she shipped many household items to New York via the Mallory Lines and rented a home there for him to live.

One of the oldest residents of the Island, Judge Darragh’s mental condition had been growing worse for months. During this time, his bank refused to recognize checks written by him unless his wife also endorsed them. He repeatedly failed to recognize his own children and suffered from confusion and hallucinations.

One such hallucination was that he had been specially delegated by George Ball to count the money in the Ball, Hutching & Company Bank. Several prominent community leaders were called to testify in the case which began the day after Christmas, including J. M. Brown, Dr. A. W. Fly, John Wolston and A. J. Walker.

Within two days, the court declared him of unsound mind and appointed his wife as his guardian. Though he was not committed to an institution, he was sent to the home prepared for him in the east where Laura visited often to arrange for his needs.

The businessman passed away in 1892, leaving instructions for his remains to be left in the Clayton-designed family vault. Of his $250,000 estate, he left $50,000 to his wife, smaller sums to a cousin and local orphans, and the remainder to his sons James and Albert.

A visitation was held at the Darragh home before the deceased was taken to St. Mary’s Cathedral for a funeral mass. The church bells which tolled announcing the service had been purchased years prior by Darragh himself.

In 1895, Mrs. Darragh purchased the famous Justine Plantation near Centerville, Louisiana, with her inheritance. She added two large rooms to the front and a front gallery with eight Doric columns. Members of the family owned the plantation until 1965. The home has since been moved to Mandeville.

During the 1900 Storm, Laura and her sons were living on one of their two sugar plantations in Louisiana. They returned to Galveston after the disaster, made the necessary repairs, and remained in the home until 1905, after which it sat vacant for three years.

A series of people then leased the property, including steamship agent Alfred Holt until 1914 and Mrs. Ellis Posey who set it up as a rooming house until 1919. The structure sustained minor damage during the 1915 Storm but remained habitable.

Mrs. August Schmidt was the next tenant, leasing furnished rooms in the early 1920s. During this time, the kitchen was used as a small furniture repair shop.

The Darragh family sold the home to M. J. Tiernan in 1921, and it remained a boarding house until Otto Trobis purchased it five years later. The west wing was detached in 1926 and converted into a duplex at 1510 Church. The Darragh mansion changed hands several more times, becoming the Taylor Apartments in 1930 and serving as a fraternity house for University of Texas Medical Branch’s chapter of Nu Sigma Nu from 1936-1953.

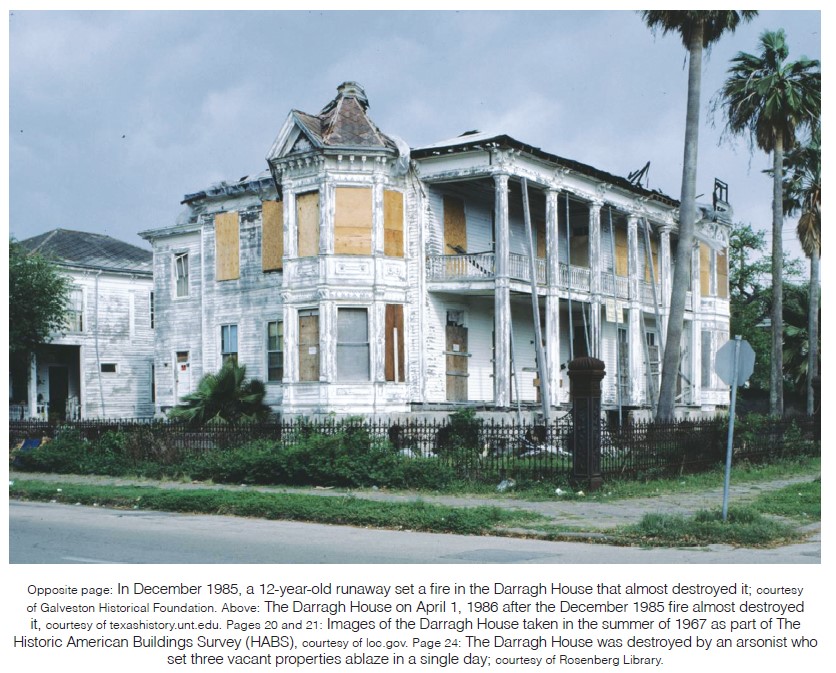

In 1954, R. D. Stanton converted the structure into eight three-room apartments and it remained apartments for years. It sat vacant in December 1985 when a 12-year-old runaway set a fire in the home, causing extensive damage.

In an effort to save the landmark, the Galveston Historical Foundation purchased the Darragh mansion in 1986 and completed $30,000 worth of restoration with the intent to resell it. The public was invited to view the residence during GHF’s Annual Historic Homes Tour in 1989.

Another arsonist fire in 1989 caused nearly $35,000 in damage but did not deter the resolve of the new owners, Mr. and Mrs. Bennie Shaffer, to restore the home. Unfortunately, another fire gutted the mansion in 1990, when an arsonist set three vacant properties ablaze in a single day.

All that remained after the Darragh home was demolished in 1991 was Mueller’s spectacular fence. A plan to sell the iron masterpiece brought vocal objections from preservationists.

Dr. E. Burke Evans, a benefactor of the East End Historical District Association, arranged for restoration of the unusual fence by Galveston sculptor Doug McLean and spearheaded the effort to purchase the property where the grand home once stood.

Anchored by the cast iron E. B. Evans Pavilion in the center, another work of McLean, the park is decorated with benches, lighting, brick pavers, crushed granite walkways, and old-fashioned roses. Darragh Park officially opened in 1998 as an homage to one of Galveston’s most unique lost mansions.