Unbeknownst to many who today seek the shores

of Galveston for respite and relaxation, Texas’

sunniest city was not recognized nor promoted

as an entertainment destination until the first section of

the seawall was built between 1902-1904. During the

19th century, Galveston was primarily concerned with

commercial pursuits and the growth of its port, and

although the eastern portion of the island’s coastline was

simultaneously lined with bathhouses, “surf-bathing” was

not necessarily considered a family-friendly activity at the

time. Galveston’s beachgoers garnered a reputation as the

unsavory sort and the bathhouses became notorious as

centers of illicit and sometimes even violent activity.

Local Galvestonians with vested interest in beachfront

business, including famed bathhouse icon George

Murdoch, viewed the construction of the seawall as a

chance to overhaul the reputation of the city’s Gulf side.

Murdoch himself contributed by purchasing a string of

real estate on the beachside between 23rd and 27th

Streets to exert a positive influence on its reestablishment

as a safe and wholesome offering to the public.

This sentiment, shared by other business owners and

residents, led to aspirations of Galveston becoming the

“Coney Island of the South,” and their collective vision

included talks of an amusement park to help advance

Galveston’s reputation and draw a more refined clientele.

Amusement parks, a concept born from an

amalgamation of traveling carnivals, pleasure gardens,

and world fair exhibitions, gained significant ground in

the 1850s and 60s after a surge of mechanical innovation

led to the invention of mechanical rides including the

carousel. These industrial advancements, coupled with

the rise of a working class who now possessed expendable

income for entertainment (heretofore not the norm),

ushered in the seemingly eternal era of modern fun fair

rides that continues to this day.

In the early 1900s, amusement parks were fast becoming a staple of seaside cities to attract day-trippers while other towns viewed their construction as a tribute to economic and industrial advancement, but Galveston had alternate motivations. In 1902, the Snug Harbor Hotel was built on the corner of 22nd Street between Avenue Q and the line of the future seawall. It was only the second hotel ever built on the southern side of the city, the first on the seawall, and the first since the 1900 Storm.

Suddenly, the prospect of overnight visitation was ignited for the first time since the famous Beach Hotel mysteriously burned down in 1898, prompting Galveston planners to latch onto an entirely different marketing strategy for their amusement park.

Their scheme was also likely inspired by the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 in Chicago, considered the immediate predecessor of the American amusement park for its introduction of the “midway” and an imaginative template that was a cross-section of engineering, entertainment, and education. Simultaneously, the Columbian Expo awed visitors with its roaring display of electric lights, earning it the nickname “The White City.”

Secretary of the Galveston Business League William Gardner adamantly proposed that visitors to the island would be more likely to stay overnight if the city could persuade them to stay after dark. The key was electricity, a cutting-edge technology viewed at the time as a novelty and a luxury. It was not distributed commercially until 1882 and progressed only gradually; by 1925, only half of U.S. homes had electricity.

To ensure that no mistake was made regarding the allure of its main attraction, the name of Galveston’s first foray into the amusement park industry was simple yet sensational— Electric Park.

Built in the spring of 1906 concurrently with a construction boom along the Galveston coast that included two roller rinks, additional bathhouses, and several more hotels, Electric Park spanned the entire city block between Seawall Boulevard, Avenue Q, 23rd, and 24th Streets. It was anchored at the corner of the seawall and 24th by the Crab Pavilion, a massive two-story, open-air space with seating and concessions built in 1905 and leased to the Galveston Electric Park and Amusement Company for incorporation into their park.

The central attraction was the Aerial Swing. The cables attached to each chair were studded with bulbs like strands of Christmas lights, and as riders rose up like a flare over the center of the park, the cables transformed into a massive strobe light that lit up the seawall for blocks. Other amusements were a roller coaster called the Figure 8 and the Cave of the Winds, a ride through a dark cavern rigged with various blowers that sent gusts and blasts across the cars as they passed.

Adhering to the educational facet almost always included in amusement parks of the time, Electric Park presented Hale’s Tour of the World, an early version of a moving picture show that depicted places of interest from across the globe. Adjacent to this was the Electric Theatre that featured a slate of live performances. Later, in a frighteningly prophetic move, the theatre’s name was changed to the Casino.

Placed throughout the rest of the park were shooting galleries, ice cream parlors, gift shops, walking paths, concession stands, benches, carnival games, and a bandstand where musicians provided a live soundtrack

that wafted through every crevice of the park, over the

seawall, and onto the beach. To complete the multi-sensory

experience, all of the structures were painted bright white

to further amplify the glow of more than six thousand lights.

Thus, Electric Park offered ambiance to more than just

its patrons. Couples and friends were known to enjoy the

spectacle from the beach, bathing not in the water but in

the luster and music that emanated from the seawall.

Construction delays postponed the opening by two weeks,

but the park was still completed in less than three months

for a stunning cost of $51,560, nearly $1.5 million today. On

the evening of May 26, Electric Park made its debut.

From 6-11pm, hundreds of invited guests roamed the

grounds, partook of various sundries, and participated in

the carnival games. The Galveston Daily News reported,

“Several thousand light bulbs completely encircling the

Crab Pavilion…gave the scene an imposing appearance and

caused the minds of many to revert to the scenes at the St.

Louis World’s Fair two years ago.”

No rides were open at the formal preview, however.

That honor was reserved for the public when Electric Park

officially opened the next day, May 27, 1906.

Unfortunately, only two of the rides were functional

even on that day, but regardless, Electric Park immediately

accomplished its purpose. The News reported that

although business along the beach was steady throughout

the daytime, the crowd along the seawall swelled after

sundown. Not all of them were necessarily patrons of the

park, and many of them were locals.

“From 7:30 till after 10 o’clock there were thousands of

people walking the seawall, bathing, walking along the

sands, or visiting the various resorts and attractions.”

Electric Park lit up the seawall, both figuratively and literally,

and added an entirely untapped dimension of nightlife to

the Galveston scene.

In 1907, notable improvements were made to the park.

Since its perimeter was surrounded by developed land and

expansion was impossible, the park was instead rearranged.

Several attractions were removed and replaced with new

ones, the most anticipated of which was the Ferris Wheel.

Adding to the excitement of the summer of 1907 was the

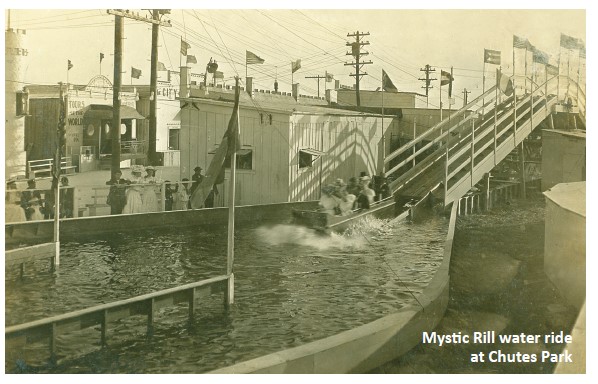

opening of Electric Park’s new neighbor, Chutes Park.

This new addition served not only to “appease the

American’s thirst for hazardous pastimes,” but also to

solidify Galveston’s fast-growing reputation as the premiere

resort city in the South. The main attraction of Chutes Park

was the Mystic Rill, a water ride that traversed a beautifully

landscaped waterway stretching more than one thousand

feet, wrapping around the Figure 8 of Electric Park and back.

At the end of the ride, the boats traveled up a steep incline

before being shot down a watery hill and concluding with a

huge splash. This was an early version of a popular ride at

the beloved but lost Astroworld called the Bamboo Shoot.

It seemed almost antiquated against a backdrop of gravitydefying

steel roller coasters, but back in 1907, “shoot-thechutes”

were the pinnacle of fun fair innovation.

Chutes Park also incorporated the educational element

with a theatre, first called the City of Yesterday and later

the Edisonian Theater, which presented titles such as “An

Astronomer’s Dream of the Other World.” Elsewhere,

a German-themed garden called Happy Land provided

concessions, picnic tables, and live vaudeville shows, the

Illusion Theater put on magic shows, and the Palace of Wonders used the same early moving picture technology as

Hale’s Tour of the World.

Other attractions of unknown design were the Giggle Alley

Castle, Katzenjammer Castle, the Klondike, Happy Island

Gardens, the New World’s Scenic Railway, the Witches’

Cave, and Wedding in Fairyland.

Finishing touches included 14 different concession stands,

electric fountains and waterfalls, and thousands of electric

lights. Together, Chutes Park and Electric Park brought an

amount of fun, entertainment, and aesthetic to Galveston’s

beachfront that was unparalleled in the south, making it a

multi-day destination.

Other attractions of unknown design were the Giggle Alley

Castle, Katzenjammer Castle, the Klondike, Happy Island

Gardens, the New World’s Scenic Railway, the Witches’

Cave, and Wedding in Fairyland.

Finishing touches included 14 different concession stands,

electric fountains and waterfalls, and thousands of electric

lights. Together, Chutes Park and Electric Park brought an

amount of fun, entertainment, and aesthetic to Galveston’s

beachfront that was unparalleled in the south, making it a

multi-day destination.

The News described, “By day, they are white, clean and

spotless and by night a gorgeous mass of lights…a hodgepodge

of sounds, some melodious, others somewhat

discordant, but none entirely disagreeable, for they tell that

something is doing ‘in the old town tonight.’”

Unfortunately, both Electric Park and its companion were

ill-fated and short-lived, but in the end, they were a worthy

sacrifice with a lasting legacy. In late October 1907, a

severe thunderstorm blew through the island and caused

significant damage to the parks, but they were quickly

repaired and in full operation by the following summer.

In 1908, Electric Park gained a ride called the Tickler with

cars that bounced gleefully as they traveled up and down a

series of inclines, and then the park miraculously survived a

hurricane that struck on July 21, 1909.

After that summer, however, the trademark aerial swing

was sold, dismantled, and moved to the newly minted Surf

Park at 32nd Street in an event that foreshadowed Electric

Park’s ultimate demise. Electric’s escape from destruction

during the July storm was an anomaly—nearly every other

structure along the seawall was decimated. This forced city

officials to make a decision that determined the park’s final

fate.

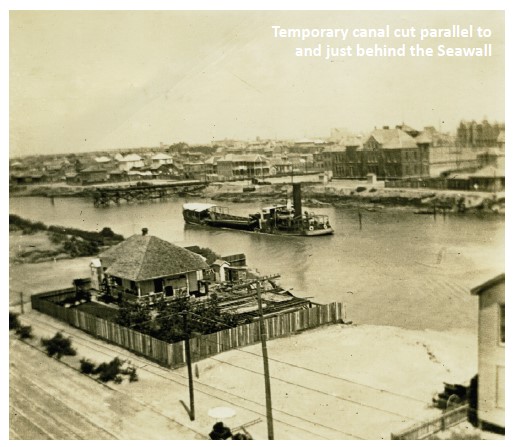

When the seawall was completed, the city of Galveston

set about achieving what it still considered one of the most

monumental feats of civil engineering ever accomplished in

the history of the United States—the grade-raising.

To facilitate the self-loading hopper dredges that were

tasked with transporting the fill dredged from the harbor over to the grade-raising districts on the opposite side of

the island, a temporary canal was cut parallel to the seawall

all the way to 33rd Street. The earth dug out for the canal

path was used to fill in behind the 17-foot-high seawall in

order to elevate the stretch of land that would become

Seawall Boulevard.

The Board of Engineers who designed the seawall and

proposed the grade-raising originally suggested that the

embankment behind the seawall measure 200 feet. Wanting

to limit the number of houses that had to be moved for the

canal, city officials vetoed the board’s recommendation and

instead limited the boulevard’s right of way to 100 feet. But

the damage left behind after the 1909 storm forced city

leaders to rethink their decision, and hoping to minimize

future destruction, they acquiesced to expanding the

boulevard to the suggested 200 feet.

The Board of Engineers who designed the seawall and

proposed the grade-raising originally suggested that the

embankment behind the seawall measure 200 feet. Wanting

to limit the number of houses that had to be moved for the

canal, city officials vetoed the board’s recommendation and

instead limited the boulevard’s right of way to 100 feet. But

the damage left behind after the 1909 storm forced city

leaders to rethink their decision, and hoping to minimize

future destruction, they acquiesced to expanding the

boulevard to the suggested 200 feet.

Electric Park was thereby no longer prime beachfront

real estate but instead found itself directly in the path of

expansion. In the fall of 1910, the rides were disassembled,

and the buildings were demolished to make way for

completion of the grade-raising.

For unknown reasons, planners spared the carousel

and the Crab Pavilion which underwent substantial

improvements prior to the 1910 summer season. A pool

hall with eight billiards tables was placed at the east end of

the pavilion, the café’s kitchen was updated, and the entire

structure was repainted and retouched.

In one of the final steps of the seven-year-long graderaising,

the pavilion and carousel were raised along with

other remaining seawall structures so that the embankment

could be widened and leveled. They remained for several

more years until the carousel was destroyed in the

hurricane of 1915. The pavilion survived albeit barely, but

the price of repairs finally came to outweigh sentiment and

it was demolished the following year.

The last remnants of Electric Park were erased from the

map more than a century ago, yet it remains forever present

in the tradition of Galveston.