Sicilian-born Anna Roberti (1887-1969) immigrated to Galveston with her Italian siblings and parents Ignazio (1854-1929) and Maria Christina (1858-1948) in 1890, when she was just two years old.

When she was 15, she met the tall, handsome Count Edgardo “Edgar” Joseph Emiliani (1874-1949) at a party. He had immigrated to the island a few years before but had not pursued naturalization in order to retain his title.

Though he was more than a dozen years her senior, Edgar was captivated by the young, black-haired Anna who undoubtedly sang at the gathering as she did at numerous events and special occasions. They were married that same year, 1903, by Monsignor John Murphy at St. Patrick’s Church.

She was kept busy in the following years with her children and home life, but Edgar encouraged his wife to pursue her vocal studies overseas, as well, sometimes leaving her husband behind. After only four trips, the young soprano made her singing debut at the St. Cecilia Conservatory in Rome, appearing with the famed opera singer Enrico Caruso.

She appeared in other cities across Italy while studying advanced voice training, always returning to her family, musical activities, and social obligations in Galveston.

In 1939, Anna went to Italy to settle the affairs of her husband’s family estate. As Italy inched closer to war with the United States, she was denied the ability to book passage home.

She later told her family that she was cursed in the streets for being an American and forced to flee to Fermo on the Adriatic Sea where an acquaintance had a villa. She and other refugees hid in the cellars, fearful of being discovered by the Italian forces.

While Anna was in hiding, she and her companions devised a way to help American and English prisoners in the area. Working with the Underground, they obtained women’s clothing from sympathetic citizens and used them to disguise escaped prisoners of war.

The incognito men were then taken to fishing boats that ferried them out of the country. The men who were aided in the efforts referred to her as “Mother Texas.”

The incognito men were then taken to fishing boats that ferried them out of the country. The men who were aided in the efforts referred to her as “Mother Texas.”

The enterprising singer also used scraps of fabric to hand sew several miniature American flags and a large one. When the Allies arrived in town, locals waved those small emblems and the large one hung from the town hall in celebration. She later told her family that no flag of silk could have been a more beautiful sight.

After the war, she was lauded by Generals George Patton and Mark Clark, awarded a medal by Pope Pius XII and given a book of autographs from her “American boys.”

When Anna was finally able to return to Galveston in 1947, she found that her love of music had intensified through the ordeal and pursued performing as well as teaching voice from a studio in her cottage home at 2015 37th Street.

Her husband Edgar passed away two years after her return to Galveston.

In November 1953, Countess Anna Emiliani took a special oath of renunciation of her title of nobility, and officially became a naturalized American citizen. She carried a special memento with her to the ceremony—the large flag she had sewn while in hiding during the war. A photo of her holding the flag appeared in newspapers across the state.

In November 1953, Countess Anna Emiliani took a special oath of renunciation of her title of nobility, and officially became a naturalized American citizen. She carried a special memento with her to the ceremony—the large flag she had sewn while in hiding during the war. A photo of her holding the flag appeared in newspapers across the state.

In 1954, she returned to Europe for an eight-month stay for further voice training. During that visit she sang the “Supreme Sacrifice,” by Dorotes Beloch, in the Vatican with the Sistine Chapel choir and orchestra.

She stayed with the Countess Sara Cruciani, who was one of her fugitive companions during the war. Other guests of the countess included several Catholic cardinals who had come to attend the canonization of Pope Pius X, officially declaring him a saint.

She also visited the church of St. Susanna, which served as the national Catholic parish for residents of Rome from the United States from 1921 to 2017. While there she had a conversation with a priest and mentioned her upcoming pilgrimage to Lourdes, France, which is one of the world’s most important sites for the faith.

The priest told her that he had received a letter from a dear friend in the Holy Land who was critically ill. The friend’s one request was for a rosary from the Lourdes shrine, which would involve a trip that the priest was unable to make. Anna offered to bring a rosary back for him.

When she returned with the rosary, he pressed a small gold, oval-shaped object into her hand. It was lined with red satin, covered with glass and included a folded note.

He explained that it was a relic of the newly canonized pope, with the documentation to prove its authenticity. A religious relic is a small piece of a personal effect of or the actual remains of a saint. In this case, it was a miniscule piece of the pope’s skin.

Countess Cruciani gifted Anna with a 16th century hammered silver repository into which the rare relic was fitted for display and safe keeping.

The singer traveled to Spain and Cuba before returning to Galveston in December, bringing along her newly acquired prized memento.

On board the ship home, Anna met a retired general and his wife who invited her to their home in Cuba for lunch, during the ship’s stop in that port. They told her that their next-door neighbor was author Ernest Hemingway, and she requested that he come to lunch as well, which he did.

She gladly resumed her quiet life teaching voice lessons upon her return to the island. She and her students entertained at local events and celebrations for years to come.

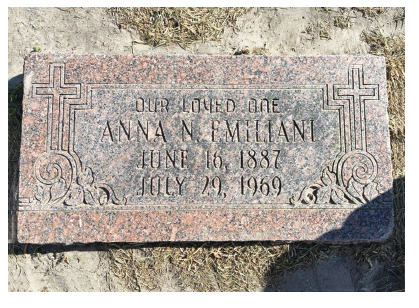

Anna died of a stroke at the age of 82, leaving behind a legacy of music and volunteerism as a source of pride for her children. The small, simple marker at her gravesite in Calvary Catholic Cemetery on 65th Street belies a life filled with enough adventure to be worthy of a novel.

It’s the quiet heroes who are sometimes misplaced in the pages of history.