In January 1912, the island was buzzing with excitement about a strange apparatus that had arrived in town with the hope of flying above the city. Charles Keeney Hamilton, one of the most famous stunt pilots of his day, and his crew uncrated parts of his newly equipped Curtiss biplane at the parade grounds of Fort Crockett and erected a temporary hangar to assemble them in.

Residents of Galveston had read about the 12-second flight by the Wright Brothers in 1903 at Kitty Hawk as well as experimental flights by other aviators around the world since then, but few Islanders had ever seen an aircraft in person. Not surprisingly, crowds gathered to watch Hamilton’s every move.

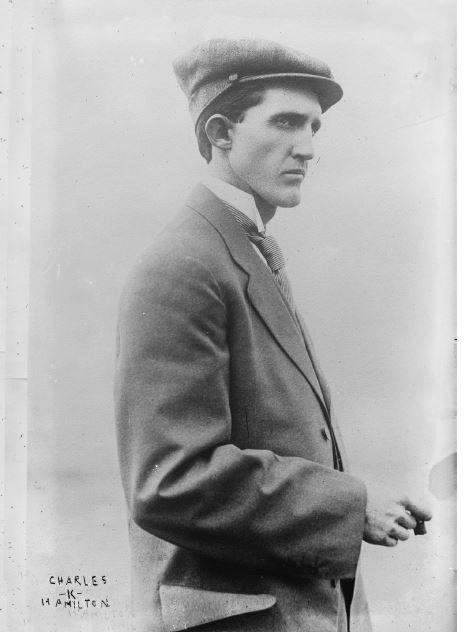

One of the best-known flyers of that time, Hamilton began hot-air ballooning and parachute jumping at circuses and fairs when he was only eighteen. Three years later he began piloting dirigibles, and by 1909 was flying exhibition shows for aviation pioneer Glenn H. Curtiss.

Two newspapers in New York and Philadelphia offered $10,000 to the first pilot who could fly from New York to Philadelphia and back in 1910, and Hamilton won it gaining instant celebrity. That same year, he listed his occupation on the United States census as an “aeronaut.”

It was a great accomplishment but what he was really known for – the same as any daredevil – was crashing. That alone drew onlookers wherever he went. He is estimated to have crashed about 60 times in his 11-year career, breaking multiple bones. The thrill of danger was as intriguing to the onlookers as it was to Hamilton.

Air shows were popular in 1909-1910, but when the newness wore off Hamilton re-ignited interest by taking his plane higher and then, giving the appearance that the engine had failed, spun to the ground as crowds screamed. It’s a popular tactic still used in present day air shows.

Though he was a master of pulling his plane out of a dive at the last minute, there were a few miscalculated stunts when he, and the plane, would end up in a heap. Luckily for him the crafts did not explode on impact like they do today.

The public was also aware of the “Bird Man’s” reputation as a heavy drinker and smoker, which added an additional element of risk.

The general opinion was that these “mad men” trying to fly in the air like a bird were surely a fad, but there were exceptions. Galveston civic leaders George Sealy, I. H. Kempner, Maco Stewart and Edmund R. Cheesborough were among the progressive minds in the Galveston Commercial Association who believed that aircraft would be a vital part of the future and were appointed to a committee to investigate bringing aviation to the area.

Houstonian Lesley Lewis “Shorty” Walker flew his own birchwood plane in Houston the year before and had set his sights on doing the same in Galveston. After taking off from Houston the wind changed, and he had to land in Webster. That failed attempt left the accomplishment of being the first pilot to fly from Galveston open for Hamilton, who he became friends with during the young aviator’s visit.

Hamilton arrived in Galveston the same month the National School of Aviation picked the city as its southern headquarters for flying instruction. Three Curtiss biplanes, a Farman, a Bleriot and a seaplane were shipped from Chicago, canvas hangars were set up and mechanics arrived to assemble the planes in the Denver Resurvey District, preparing Galveston to play an important role in early American aviation. The school was overseen by Mart McCormack, who held the American record for passengers in an airplane, carrying three people in addition to himself.

On Friday, January 19, Hamilton thrilled the crowds with three separate flights cruising around the fort grounds and over the gulf water at 40 miles per hour. Although short in duration, they were proclaimed a success in the local newspapers, with headlines such as “Daring Flier Glides over the Gulf,” “Reaches Dizzy Altitude of 2,000 feet,” and “Sensational Night Flight over City.”

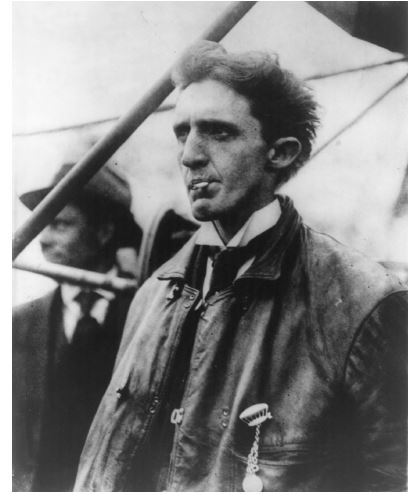

On Saturday, the crowds who gathered at the parade grounds were rewarded with the sight of three more flights by Hamilton, these being longer and more daring than the day before. He arrived in a long leather coat and leather helmet and paused only long enough to answer questions from curious bystanders before climbing aboard the Curtiss.

Showing off his “aeronautic” skills, the pilot executed difficult dips, turns and spiral glides and even circled the Hotel Galvez causing guests to rush to the windows and spill from the doorways in delight. He then returned to the parade grounds and gracefully touched down before returning to the Galvez by a much more conventional method.

Hamilton spent most of the day Sunday at his headquarters at the Hotel Galvez with friends, no doubt spending a bit of time celebrating at the bar. At 3:30 p.m. they left the hotel to visit the aviation school grounds to watch the progress of assembling a 75 horsepower Curtiss engine.

At 5:30 p.m. he went to his own temporary hangar at the fort, where his plane was quickly rolled into position at the west end of the parade grounds. Only about 50 of the 5,000 people who had waited to see him that afternoon remained to witness him taking to the air twenty minutes later.

The first flight Sunday was made at 5:50 p.m., when the birdman took to the air at Fort Crockett and for ten minutes circled the fort grounds before gliding out of sight.

It was said to be the “prettiest” he had made since his arrival, passing over the batteries of the fort, proceeding north over the links of the Galveston Golf Club, west above the aviation school and then back to the beach where he dipped within 20 feet of the breaking surf. The aviator then circled the fort grounds and eventually landed to the applause of onlookers.

Before darkness fell, Hamilton decided to experiment with the weight of a passenger. While a flight was not made, witnesses anxiously watched as A. C. Doty, Hamilton’s mechanic, seated himself on the lower part of the plane next to the engine. A successful “jump” of about 100 yards was made before landing, with Hamilton maintaining the balance of the craft.

Before darkness fell, Hamilton decided to experiment with the weight of a passenger. While a flight was not made, witnesses anxiously watched as A. C. Doty, Hamilton’s mechanic, seated himself on the lower part of the plane next to the engine. A successful “jump” of about 100 yards was made before landing, with Hamilton maintaining the balance of the craft.

Late that night, with most of the city sleeping below, Hamilton made the most daring flight of his Galveston visit. Only a few friends new about his plan.

He left the Galvez in an automobile at 10:30 p.m. and went to Fort Crocket where his team was preparing for the take-off. Hamilton became airborne shortly before 11 p.m. and took an easterly course before circling back to fly over a large part of the island south of Broadway.

After turning towards the gulf, the pilot flew over the water near the Surf Bathhouse at 33rd and Seawall, circled twice around the towers of the Galvez, and then glided to a landing on the boulevard directly in front of the hotel. Hamilton shared that during the half hour flight he estimated reaching between 800 to 1,000 feet but was unable to gauge the altitude exactly in the darkness.

He flew the plane back to the parade grounds the next morning, but the sight of the flying machine parked on the boulevard when the sun came up undoubtedly surprised numerous people.

Birdman Hamilton kept Galvestonians in a flurry of excitement with flight performances, and almost as many postponed feats. Crowds arrived to witness announced flights on several occasions only to have them called off due to adverse winds or mechanical trouble.

One of the most talked about stunts during Hamilton’s flights was a race against George Sealy’s new Marmon roadster along the beach.

There were a handful of scares during his time on the island however, such as a flight over the water during which his leather helmet came loose and threatened to get caught in the propellor. The quick-thinking pilot quickly snatched the helmet and threw it away from the plane, and it later washed ashore.

Hamilton’s landing on the parade grounds on Friday, January 26 was not as successful as his previous attempts, and his craft crumpled upon landing, dismembering the plane and breaking Hamilton’s collar bone. Doctors at the hospital announced that he would be able to fly again in three weeks, but the stubborn pilot returned to his hanger two days later.

The remainder of his exhibitions were hampered by weather, rather than his injuries, preventing him from leaving the crowds on a positive note.

Hamilton left Galveston on February 10 with a bandaged neck and his right arm in a sling as souvenirs of his island visit. The motor of his Curtiss and the few parts which were not destroyed in the “fall” during his last exhibition on the island were packed up and shipped to the west coast where they were built out into a new machine.

Hamilton, the first pilot to take off and fly from Galveston Island earned a quarter of a million dollars over his spectacular but short career but kept very little of it. He died on January 22, 1914 at the age of 28 from tuberculosis. At his funeral, a group of aviator friends flew over his gravesite as a tribute.

Hamilton, the first pilot to take off and fly from Galveston Island earned a quarter of a million dollars over his spectacular but short career but kept very little of it. He died on January 22, 1914 at the age of 28 from tuberculosis. At his funeral, a group of aviator friends flew over his gravesite as a tribute.

In the years that followed Hamilton’s Galveston flight, numerous aerial performers flew along the seawall thrilling visitors and locals.

The attention to air travel opened other doors, as well. Galveston Postmaster Harry A. Griffin established a postal sub-station adjacent to the aviation school facilities.

Pilot Paul Studensky, an instructor at the school, flew a Curtiss biplane from the facility about 15 miles to Virginia Point, where he landed, delivered a pouch of mail to the waiting postmaster who presented him with a receipt for it. Studensky took off and returned to Galveston.

The air flight demonstration was sponsored by the Galveston Chamber of Commerce. Today they are so commonplace as to not be given a second thought.

The next time a small plane glides through the air above Galveston, perhaps Islanders can stop for a moment to consider how daring early aviators flew the same path.