The humble

granite block- it sits silently, faithfully serving this island city. For most

people these blocks are little more than convenient platforms extending into the

surf, places to enjoy the sights and sounds of crashing waves. They benefit

fishermen on sunny mornings and the aquatic sea life living in their crevasses.

They tend to blend into the scenery, and little thought is given to them.

The story of Galveston’s granite holds much more

significance than its silent presence indicates, but its place in island

history is usually overlooked. Etched in this seaside stone is the story of a

city's perseverance and the dreams of powerful men.

It begins over 130 years ago, deep in the Texas hill country near a place now called Marble Falls.

It was here that a quarry was established to extract pink granite from a

200-foot-tall geological dome formation. This formation, the remains of ancient

volcanic activity, would be given the name Granite Mountain.

It begins over 130 years ago, deep in the Texas hill country near a place now called Marble Falls.

It was here that a quarry was established to extract pink granite from a

200-foot-tall geological dome formation. This formation, the remains of ancient

volcanic activity, would be given the name Granite Mountain.

In the

early years, the quarry brought in skilled stone cutters from Scotland, and teams of convict laborers, to mine

pink granite for the construction of the Texas

state capitol. But the same quarry a short time later would host another team

called the Galveston Company, arrived to mine stone for an amazingly large

project.

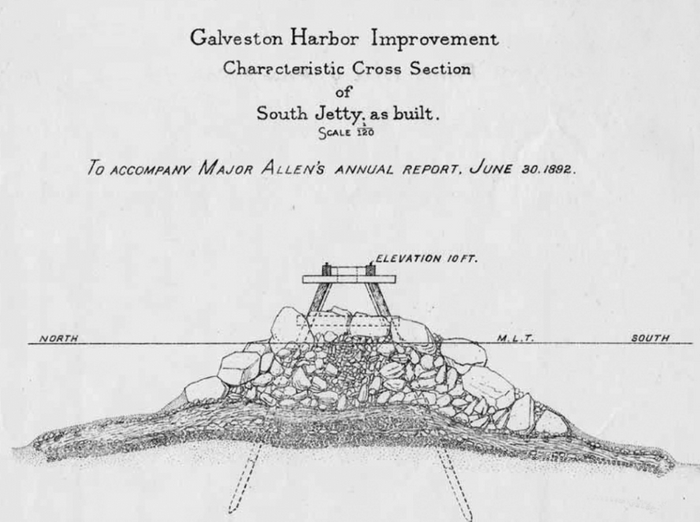

Their job was to cut tens of thousands of

giant blocks weighing between three and seven tons to build Galveston's north and south jetties. The south

jetty at the extreme east end of Galveston

Island would eventually be five miles

long, while the north jetty at the tip of Bolivar

Peninsula would extend an incredible six

and a half miles into the Gulf of Mexico.

After the huge blocks were mined from Granite Mountain, they were loaded onto rail

cars and delivered to the coast. Rail trestles were built miles out over the

water where the stone blocks were carted and carefully placed into their

positions, creating the jetties. The Jetties are composed of a sandstone core

and covered by the giant granite blocks. Jetty construction was completed in

1898.

After the huge blocks were mined from Granite Mountain, they were loaded onto rail

cars and delivered to the coast. Rail trestles were built miles out over the

water where the stone blocks were carted and carefully placed into their

positions, creating the jetties. The Jetties are composed of a sandstone core

and covered by the giant granite blocks. Jetty construction was completed in

1898.

Political

Will And Money Come Together

The struggle to acquire these jetties was

long and uncertain but completely necessary for the city's economic survival. In

these early years, Galveston's

seaport was its beating heart. It was the driving force of the city's economy

as well as the city's very identity.

By the 1870s, this thriving seaport enabled Galveston to become one

of the wealthiest cities in the nation, per-capita. However, by the late 19th

century, it was clear that future success of this seaport was becoming

increasingly less certain.

The times were changing. The industrial age

had arrived, steamships were replacing sailing ships, and ships were getting

bigger. The introduction of larger vessels revealed an underlying problem,

quite literally - sandbars. Galveston

became increasingly reliant on lightering, the practice of anchoring a ship in

deeper water offshore and unloading the cargo into smaller vessels to get it to

the docks. Lightering is an expensive and inefficient process.

Subsequently,

competition grew among the nation’s seaports to attract the business of these

modern-era shipping lines, and soon, a rating standard was set into place. A

first-class rated seaport had a depth of 26 feet or deeper. A second-class

seaport had a depth of 20 to 25 feet, while a third-class port was less than 20

feet deep.

Galveston's

sandbars restricted the depth to a humbling eight feet of water at low tide. The

proud island city, with its wealth and opulence on full display, refused to be

humbled by lowly sandbars, and could not suffer the indignity of being labeled

a pathetic third-class seaport. Something had to be done.

This was the moment for leaders to lead. One

man stood up to the challenge, Colonel William L. Moody. This former civil war

officer who had made his fortune in cotton and banking would now lead a

committee of men which included some of the city's most successful and influential

residents. John and George Sealy, Harris Kempner, Colonel Walter Gresham, and

other members of the city's ruling elite were assembled to brainstorm the

problem. They met at the old Cotton

Exchange Building

and were titled the Deep Water Committee, or the DWC.

The sandbar problem was nothing new, and in

preceding years, other attempts had been made to combat the problem, from

driving pilings under water, to using gabions, which were large, submerged,

sand-filled baskets. These were feeble attempts and complete wastes of money.

The DWC knew that realistically, at least two

things would be needed to insure permanent deep water. First, they would need

stone jetties, and second, federal dollars to acquire them.

Soon, the DWC embarked on a political crusade

for deep water that in the end lasted more than ten years before it finally

succeeded. In the beginning, they were motivated by the recent success of New Orleans, which had

its own deep-water battle to conquer. The DWC set out to do exactly as New Orleans had done and

hired the same engineer.

First,

however, they would need the federal subsidies. In the 1880s it was not that

common for the federal Government to freely pass out millions of dollars. In

their quest, members of the DWC would spend years lobbying within Texas, as well as in

neighboring states, campaigning for congressional support for a deep-water

bill.

Colonel Gresham was sent to Washington, D.C.

to do the same. It was an uphill battle as other cities were competing for the

same money.

The bill was so important to Galveston that eventually, members of the DWC

felt that in order to sway favor with a republican congress, they would need to

elect a republican to congress. This was pure politics.

The bill was so important to Galveston that eventually, members of the DWC

felt that in order to sway favor with a republican congress, they would need to

elect a republican to congress. This was pure politics.

The American Civil War was not that distant

in the past and these former Confederate army officers would ordinarily want

nothing to do with the hated Republican Party, the party of Lincoln. Eventually, they did succeed in

getting Republican R.B. Hawley elected to congress - the first Republican

elected south of the Mason-Dixon Line since

before the civil war.

In another reach for influence, a member of

the DWC had informed President Grover Cleveland of the excellent fishing in Galveston and invited him

to come down and enjoy the experience. In a stroke of good luck, Cleveland accepted the

invitation.

The Galveston Harbor Bill was finally passed

by the senate in 1890 and shortly after was signed by President Cleveland. With

this news the city burst into celebration. A holiday was announced, and

whistles were blown jubilantly throughout the city.

Over the following years, thousands of

granite blocks were railed to the coast. By 1896 much of the Jetty project had

been completed and the mouth of Galveston

was dredged to measure between 27 and 40 feet deep.

Over the following years, thousands of

granite blocks were railed to the coast. By 1896 much of the Jetty project had

been completed and the mouth of Galveston

was dredged to measure between 27 and 40 feet deep.

That year, Galveston's Artillery Company gave a one-thousand

cannon salute on the beach to celebrate the arrival of world’s biggest cargo

ship, the Algoa. Shipping soon

doubled and in less than a year, Galveston had

become the world’s second biggest cotton port, second only to Liverpool, England.

Meanwhile back at Granite

Mountain, the quarry remained a busy

place as Galveston's

appetite for granite was not yet satiated. A few short years after the jetties

were completed, the 1900 Storm devastated the island, and the quarry once again

came to the city's aid as tons of crushed granite was needed for the aggregate

of the new concrete seawall.

As the 20th century progressed, Galveston was changing

more and more. The Port of Galveston no longer had the prominence that it had

held in the prior century, and it risked being overtaken by the Port of Houston.

Galveston

was now transforming into a tourism destination. With the addition of the

seawall, visitors were now coming to Galveston

to enjoy the beach, and this demographic was becoming a mainstay of the city's

economy.

By the 1930s, it was becoming clear that the

city needed a way to preserve and even increase beach sand for the enjoyment of

the visitors. In the 1960s, granite blocks were once again brought in to create

small jetties along the seawall known as groins. The purpose of these was to preserve

beach sand and collect it from the flowing currents.

By the 1930s, it was becoming clear that the

city needed a way to preserve and even increase beach sand for the enjoyment of

the visitors. In the 1960s, granite blocks were once again brought in to create

small jetties along the seawall known as groins. The purpose of these was to preserve

beach sand and collect it from the flowing currents.

The groins have served their purpose

satisfactorily, and in addition, they have added an interesting and curious

aesthetic to the Galveston

beach-going experience.

The

efforts of William L. Moody and the Deep Water Committee have been both long-lasting

and far-reaching. After 130 years, it is apparent that the results of the Galveston

Deep Water Bill have greatly magnified to benefit the entire region,

particularly to Galveston's

old rival. The increased Gulf access has benefited the Port

of Houston greatly as it journeyed to

become one of the largest seaports in the nation and propelled Houston to becoming the fourth largest city in

the country.