Ask any first-time visitor to Galveston how long it takes before they notice something that refers to the Island’s horrible history with hurricanes. There’s no escaping it. Within minutes of arriving here, a visitor will see a watermark sign on the side of a building or hear a tour guide mention the word “hurricane.” References to hurricanes are literally everywhere. You’d think that was the only kind of natural disaster that ever happened in Galveston.

Wrong.

This month marks the 135th anniversary of one of the most devastating fires in Texas history. It happened, appropriately enough, in the wee hours of the morning on Friday, November 13.

AN EXPLOSION AT THE VULCAN FOUNDRY IGNITES THE GREAT FIRE

Witnesses reported that a howling north wind had blown the sparks from a furnace that had exploded in the Vulcan Foundry located between 16th and Strand streets, igniting an inferno unlike anything since the Great Chicago Fire in 1871. “The scene was sublime in its awfulness,” continued the same Daily News report, published the next day. “The combined efforts of every fire department in all of Texas would have been ineffective against this blaze.”

Ironically, in the month just prior to the fire, Galveston had finally allocated funds for a paid (not volunteer) fire department. Around 2:15 a.m. - over a half hour after the fire had already engulfed several buildings downtown - the alarm bell on top of the old Market House on 20th Street was rung. Six fire stations answered the call. But there were no fire hydrants near the fire.

Reporters witnessed valiant efforts to blow saltwater out of the bay at the fire, but the north wind blew the suction pipe out of the water. “All the fire departments just looked on helplessly,” said the news reports.

Fire departments from Houston and other nearby communities were summoned. They rushed to Galveston to render assistance, to little avail. Several reports stated that the fire had already consumed three full city blocks in the downtown area within a half hour.

“A CONFLAGRATION UNLIKE ANYTHING SEEN BEFORE”

Witnesses said that the conflagration had moved unchecked from block to block, blown by the relentless wind. Residents, roused by the alarm bell and the commotion in the middle of the night, began frantically moving their possessions and household goods out on the sidewalk in hopes of saving them from their burning homes - only to watch them reduced to cinders there on the sidewalk. The fire spared almost nothing.

All frame buildings in the downtown area with the exception of a random few were destroyed. Firefighters tried to focus their efforts on a lumberyard between 16th and Mechanic streets, but the dry wood burned like kindling.

“Onlookers and firefighters misjudged the extent of the fire,” said the Daily News report. “This is a conflagration unlike anything seen before. People left their homes to help at the lumber yard, not realizing their own homes were on fire.”

Moving faster than lightning, the fire advanced from 16th to 18th street, then to Strand, Market and Mechanic. There was no hope of catching it north of Broadway. Witnesses simply stood by and watched helplessly.

“THE FOUNDRY LOOKED LIKE A BLOWTORCH SENDING FIRE INTO THE SKY”

It was almost necessary to evacuate the prisoners held in the jail, but the stone building and the courthouse both withstood the flying, burning sparks. It was reported that Jailer Brown, whose own house was in flames, did not leave his post at the jail.

“Everything curled up like burning paper,” said the Daily News report. “The eastern limit of the blaze was 17th Street. Only the Gulf could check the fury of this fire. Dr. Trueheart’s residence stood, but everything else in the four blocks between Ave K and Ave O was gone.”

Even brick walls did not stop the flames. With the aid of the wind, the sparks just flew over and continued devouring buildings. “The Foundry looked like a blowtorch sending fire into the sky,” said the news report. “Only a few random houses in the area have been left untouched. There is one house on Church and 16th streets that was saved, by some miracle.”

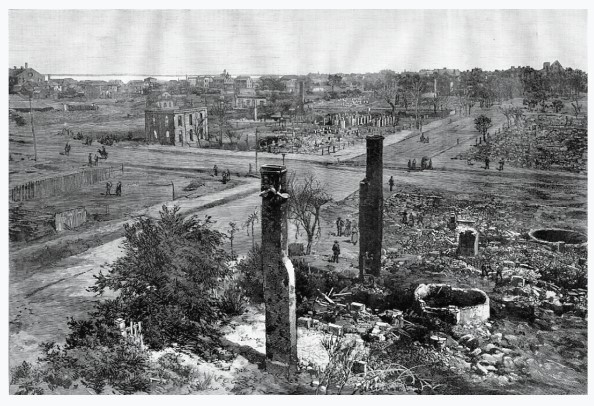

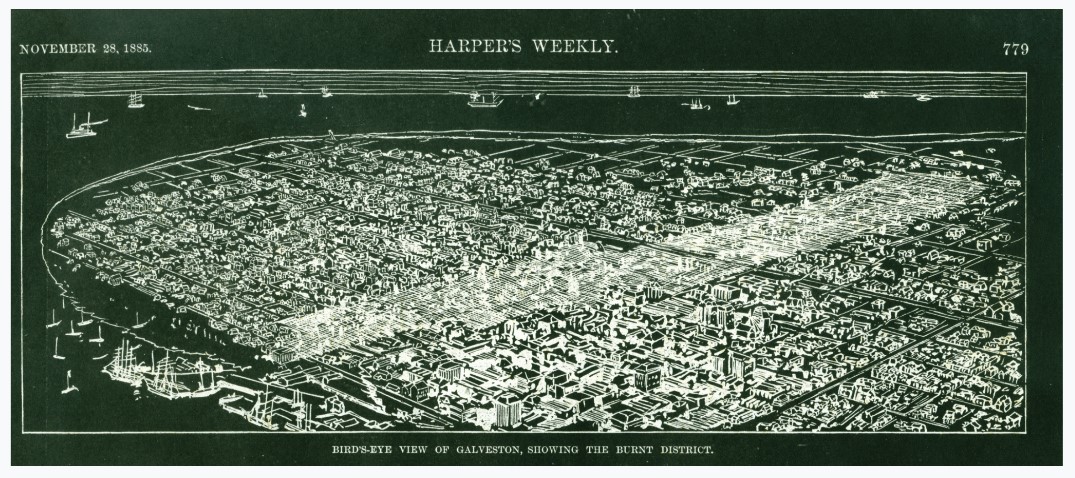

Traumatized residents said that The Strand was a solid sheet of fire. At around 7 a.m. on the morning of November 13, the fire finally burned itself out, having destroyed 100 acres of land and 40 city blocks in Galveston’s downtown area. Over 2000 families were left homeless, with 568 houses left in smoldering rubble. In 1885, the monetary damage to property was set at $2 million - an estimated $50 million in today’s market.

PLENTY OF CRITICISM, BUT NO FATALITIES

Criticism of Galveston’s new fire department, especially Fire Chief William Oldenberg, was swift and severe in the aftermath of the disaster. Although firefighters had done all they could, the alarm had come too late and they simply lacked the training, the tools and the equipment to fight a fire of that magnitude.

Many Galvestonians had been very vocal in their opposition to funding a fire department, and in the wake of this disaster, felt justified in saying they had certainly not received their money’s worth. But incredibly, there were no fatalities in this fire. However, for years afterward, Friday the 13th remained a “hoo-doo” day in Galveston’s fire department.

FIRE RELIEF

By the next day, word had spread to the mainland and beyond about the catastrophe that had befallen Galveston. The Daily News headline screamed, “A Great Holocaust! More than 40 Buildings Destroyed and 100 Acres in Heart of City Laid Bare!”

Even the November 15th edition of the New York Times covered the story. Telegrams began pouring in from all over the country. The city park was quickly turned into a lost-and-found for unclaimed items that had somehow managed to survive.

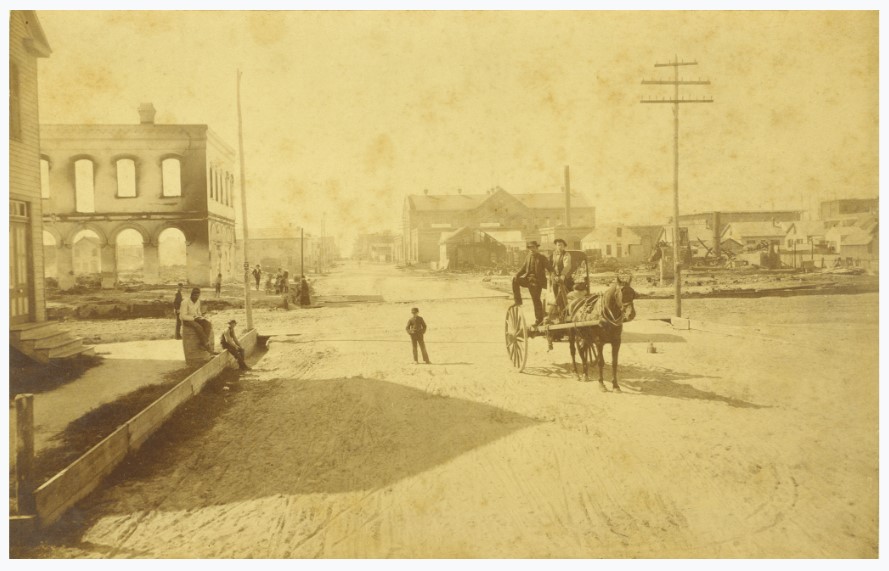

Headed by W.L. Moody, the Relief Committee swung into action and rebuilding began within a week, and continued through the winter. Some of Galveston’s homeless moved into the brick jail and the courthouse buildings, which had survived, as well as the old Lyon School.

Sightseers and gawkers flooded the city. It was reported that over 20,000 people came to look at the ruins of Galveston and watch the rebuilding process take place.

CHIEF OLDENBERG’S FIRE SAFETY TIPS FOR GALVESTON

As the city moved forward from this disastrous event, Chief Oldenberg issued a few fire safety tips for the public.

Always turn in an alarm! Put the number of your nearest fire station by your phone so that you can tell Central immediately.

Don’t run back into your home to save trinkets!

Women, tear off your skirts so they do not catch fire.

Do not run frantically from room to room, as it only fans the flames.

GALVESTON’S HISTORIC FIRE DEPARTMENTS

HOOK AND LADDER COMPANY NO. 1

This was the first permanent, all-volunteer organization for fire protection on the Island. The result of efforts from Albert Ball and others, this company was instructed to confer with the mayor and create bylaws for the fire company.

They created a set of bylaws and a constitution, which were adopted on December 3, 1843. For $226, this company purchased its first piece of firefighting apparatus, which was built by a blacksmith on Mechanic Street.

Albert Ball was chosen as the Chief of the Galveston Fire Department in 1852. The Department had 42 members. Their uniform was red shirts, white belts and black pants. The Hook and Ladder Company disbanded during the Civil War, then reorganized in 1866. Their fire truck was housed at 17th and Mechanic - in the heart of the very area that would be burned to the ground in 1885.

WASHINGTON FIRE COMPANY NO. 1

As the Island’s population increased, so did the need for more firefighters. In 1847, the Washington Fire Company No. 1 paid $1000 for a hand engine, which was shipped in from New York. The hand engine was able to throw two good streams of water and it arrived in the Port of Galveston in 1850.

As the Island’s population increased, so did the need for more firefighters. In 1847, the Washington Fire Company No. 1 paid $1000 for a hand engine, which was shipped in from New York. The hand engine was able to throw two good streams of water and it arrived in the Port of Galveston in 1850.

In 1866, they paid $8,000 to purchase another steam engine and employ engineers to test its stream efficiency. It caused quite a sensation in Galveston. This steam engine was able to raise steam in just over two minutes, and had 50 feet of hose with a one-inch nozzle that could throw water up to 179 feet. This steam engine attracted the attention of fire fighters from all over the state.

ISLAND FIRE COMPANY NO. 2

This fire company organized on March 7, 1856 and was housed in a wooden building on Mechanic and 17th. In 1866, it acquired a Silsby steamer, which provided effective service until it was exchanged for a more up-to-date model in 1871.

The Island Fire Company was known to be a very active social and political force to be reckoned with on the Island.

THE OLD AXE COMPANY

Organized on March 7, 1857, this 26-member company carried axes to tear down burning frame buildings to keep them from spreading the fire. The company was maintained until the Civil War, when it was disbanded and did not reorganize. John Gernand earned $90 a month as chief of this company.