Today, when we hear about a tragedy or major

news event, we don’t need to go any further than our televisions, computers or

phones to find endless details and videos of the occurrence. People in years

past were no less inquisitive, but with motion pictures still in their infancy

and limited newspaper photographs, their curiosity was often less than

satisfied.

The

Great Storm of 1900 Strikes Coney Island,

New York

At the turn of the century, New

York’s famous Coney Island had

plenty of showmen who were happy to capitalize on this somewhat morbid

curiosity by providing visual spectaculars that immersed the viewer into

reenactments of the world’s greatest calamities. In those days, visitors to Luna Park on

Coney Island could take make-believe journeys

around the world and experience recreations of the massive disasters they had read

about in the news or in books.

On any given day, one could witness a staging

of the Boer War featuring real Boer War veterans, a recreation of the

destruction of Pompeii by its legendary volcanic

blast, relive the frightening effects of a San Francisco

earthquake, or view a village of the headhunting Bontac tribe of the Philippines

with actual tribesmen on display.

Among the

earliest of these shows was the “Galveston Flood,” created in 1902 by the

Imperial Amusement Company to re-enact the horrors of the 1900 Great Storm,

which had killed thousands of people here in Galveston only two years earlier.

In the show’s opening year, the Broadway

Weekly gave the “Galveston Flood” rave reviews, stating, “In all the years

that ambitious efforts have been made to reproduce historical scenes, there has

never been anything which approaches such perfection, in realization of all the

harrowing details, as the Electro-Aqua Scenic-Mechanical Exhibition of the

Galveston Flood at Coney Island.”

The show was housed

in an immense white building on Surf

Avenue, which dwarfed the surrounding structures.

The auditorium stage, said to be the largest in the country at the time,

measured 125 feet wide by 90 feet deep.

The show was housed

in an immense white building on Surf

Avenue, which dwarfed the surrounding structures.

The auditorium stage, said to be the largest in the country at the time,

measured 125 feet wide by 90 feet deep.

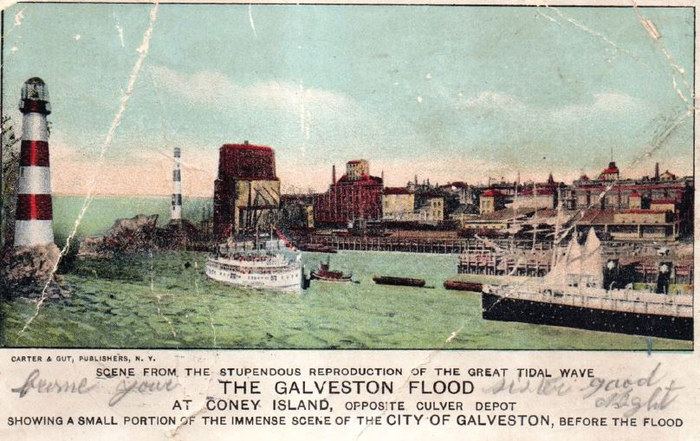

Galveston and its harbor were meticulously

recreated in miniature with intricate lighting, individual model buildings,

working railroad cars, streetcars and ships all electrically powered to portray

the goings-on of an average workday. The mechanics required a large

amount of electricity and were so advanced for their time that they were

featured in national electrician magazines of the day.

Each half-hour,

crowds poured into the auditorium to witness the tragedy for themselves. As a

narrator explained the sequence of events, visitors would watch the progression

of the storm, hundreds of buildings being washed away by torrential rains and

wind, and fires erupting among the ruins of the city.

Audiences watched with terror and excitement

as actors portraying Galvestonians risked their lives to rescue fellow victims,

and parents sacrificed their lives to save children. The force of the show’s

waters was quite treacherous, and during at least one performance workers were

hurt badly enough to have to close the show and rescue the injured, making the

news the next morning.

On

August 16, 1904 the New York Times

reported a special one-time addition to the show. “The managers of the

Galveston Flood Coney Island entertained 50 Texans yesterday. Three of them are

survivors of the big deluge that destroyed so many lives in Galveston a couple of years ago. One of the

three replaced the lecturer for a few minutes and told about his experiences at

the time of the flood.”

On

August 16, 1904 the New York Times

reported a special one-time addition to the show. “The managers of the

Galveston Flood Coney Island entertained 50 Texans yesterday. Three of them are

survivors of the big deluge that destroyed so many lives in Galveston a couple of years ago. One of the

three replaced the lecturer for a few minutes and told about his experiences at

the time of the flood.”

At the end of each

performance, crowds left the building with the complex model in a state of

apparent demolition, and rushed to purchase “before” and “after” scenes from the

show on postcards to send home. Massive electric pumps then drained the water

from the stage and the city was “reborn” for the next audience.

For those patrons who had not witnessed

enough destruction, the owners of the Galveston

exhibit even offered free shuttle service over to the “Johnstown Flood”

disaster show.

For those patrons who had not witnessed

enough destruction, the owners of the Galveston

exhibit even offered free shuttle service over to the “Johnstown Flood”

disaster show.

The “Galveston Flood” structure survived the

devastating Coney Island fire in 1911 and spent

its last remaining years as a dime museum and arcade. It was eventually demolished

in the 1950s to make way for the aquarium that is located on the same spot to

this day- the New York Aquarium.

The

Great Storm Engulfs the 1904 St. Louis

World’s Fair

Two

years after Coney Island debuted the “Galveston Storm,” the 1904 World’s Fair

in St. Louis followed

the trend with its own version. Located in the Pike area of the fairgrounds,

the exhibit, which opened on May 20, was designed by E.J. Austin and took 100

people to operate the mechanical and electrical effects.

For just

25¢ adult admission and 15¢ for

children, families could witness the catastrophe every hour of the day. As it

was at Coney Island, the city was recreated in

miniature and was destroyed by the forces of wind and water amid flashes of

lightening and thunder. A man narrated the events in melodramatic tones, while

a young lady played mood music on a piano set at the side of the stage. Only

the gruesome deaths were omitted from this performance.

One

major difference occurred in the St. Louis show

that hadn’t drawn attention on Coney Island:

Galvestonians took issue with the fact that the show ended on such a

downtrodden tone.

C. R.

Kitchell and John Reymershoffer, representing the Galveston Chamber of

Commerce, and George Sealy, representing the Galveston Business League, went to

St. Louis and attended two performances of the

“Galveston Storm” and alleged that it did not represent Galveston as rehabilitated and improved. The

city representatives specifically cited that the new Seawall was depicted as

shorter than it actually was.

According

to the Galveston Daily News on June

25, 1904, the show management agreed to make some improvements and additions to

avoid litigation over the matter. “Mr. Kitchell said that the management

received the committee very cordially and expressed themselves desirous of

doing everything possible to represent Galveston

in its true light. The also offered to insert any statements in the lecture or

eliminate any feature the committee deemed improper. The management agreed to

build the balance of the wall and also to show Galveston as it will appear when the grade is

raised.”

According

to the Galveston Daily News on June

25, 1904, the show management agreed to make some improvements and additions to

avoid litigation over the matter. “Mr. Kitchell said that the management

received the committee very cordially and expressed themselves desirous of

doing everything possible to represent Galveston

in its true light. The also offered to insert any statements in the lecture or

eliminate any feature the committee deemed improper. The management agreed to

build the balance of the wall and also to show Galveston as it will appear when the grade is

raised.”

By the next day, when the

three men attended a show at the invitation of the management, an entirely new

ending had been scripted, complete with uplifting music and the appearance of a

painting of the rejuvenated city at the end of the performance. The changes

seemed to be popular ones with the audiences as well, and the exhibit brought a

profit of nearly $200,000 for investors.

Whether considered morbid

curiosity or the “need to know,” human nature hasn’t changed much in the last

century. Crowds still flock to learn all the grisly details about tragedies

such as the sinking of the Titanic or

to view Ground Zero in Manhattan.

The catastrophe of the Great Storm of 1900 proved to be just the ticket for

out-of-state amusement event managers seeking a profit, as well as for curious

crowds seeking horrors and thrills.