It seems appropriate that Galveston’s fabled past includes a long lost castle. Heidenheimer Castle once sat on the northwest corner of Sixteenth Street and Sealy Avenue on the island’s prestigious East End.

The original portion of the home was built in 1857 at 1602 Avenue I (Sealy) for former Galveston Mayor John Seabrook Sydnor in a much more understated architectural style than it displayed inlater years.

A rectangular, Greek Revival structure with a hipped, slate roof was designed with a centralhallway and staircase flanked by two rooms on each side, both upstairs and downstairs. The walls were constructed of bricks made from “tabby” concrete, created by burning oyster shells to create lime, and then making the lime with water, sand, ash, and broken oyster shells. The home is thought to have been the second poured-brick structure built in the United States.

Sydnor was the first man to cultivate oysters in Galveston waters so, in theory, he would have had ample access to shells for the process that was considered innovative in his day. He had previously lived at the Powhatan House that was built in 1847, which his family constructed of lumber and millwork imported from Maine.

A successful businessman, Sydnor had many financial interests, including railroads, real estate, and a profitable commission business. He constructed a brick wharf, and advocated a bridge connecting Galveston Island to the mainland, schools, and police and fire departments for the city. Sydnor could afford the finest things available at the time. ‘Modern’ fixtures and appliances were added to the home when the island got gas in 1859, and later electricity replaced

its lamps.

The darker side of Sydnor’s story involves his fame for operating the largest slave market west of New Orleans, acting as his own auctioneer. A slave owner himself, the booming voice he employed to sell slaves in both Galveston and Houston was well known.

Rumors about Sydnor claim that it he brought slaves to the house to be auctioned off on theblock, transporting them from ships in the bay through a secret tunnel connected to a basement. They were supposedly kept in the basement until the time for auction at the southwest corner of Fifteenth and Postoffice. There is not much merit to these claims, however, since the original home did not have a basement, and later owners of the home found no trace of tunnels after thorough searches. The sandy nature of the soil would also make their existence unlikely.

After the Civil War, Sydnor left Galveston for New York, where he established a brokerage business that arranged for goods and supplies to be sent to Texas. H e died in 1869, while on avisit to his son in Lynchburg, Texas. He was buried in Galveston’s Oleander Cemetery.

His son, for whom Seabrook, Texas was named, was in charge of Sydnor’s interests, and he sold his father’s home to Barnabas T. Loring of Boston for $7,000.

Multiple newspaper advertisements in the years that followed reveal that the home became a rental property with an ever-reducing price tag. The home’s most colorful chapter, and the one that earned it the nickname of “castle,” began when Loring sold the property to Samson Heidenheimer for $2,250 cash, in 1884 - an estimated $65,000 today.

Heidenheimer was already intimately acquainted with the property, having been mentored by Sydnor and acted as a rental agent for Loring. His plans for the home, however, would in no way reflect its past.

Heidenheimer arrived in Galveston about 1858, after briefly settling in New York where his sister was living. As a German citizen, he was not called to serve in the Civil War, so he stayed on the island and smuggled cotton for the Confederacy to British ships waiting outside of the blockaded harbor. The enterprise was reported to have netted him a small fortune during the war.

The merchant’s business dealings also included serving as director for the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, managing a paper bag company, and operating a wholesale grocery and commission business with his brothers. Stories have it that he began by running a coffee stand on the Strand in front of George Rains’ bar, but this is likely just a bit of colorful local folklore.

He did have a flair for the dramatic, and he made headlines in the early days of the Port of Houston. He had shipped a load of salt up the shallow Buffalo Bayou, and the shipment was caught in a rainstorm dissolving it entirely. The Galveston News printed the sarcastic headline, “Houston at Last a Salt Water Port: God Furnished the Water and Heidenheimer Furnished the Salt.”

Samson and his wife Anna had no children of their own, though their niece Rosa lived with them for a short time. This might explain why they were able to focus their attention on a grand expansion of the home on Sealy that began in 1885, and cost an astonishing $20,000.

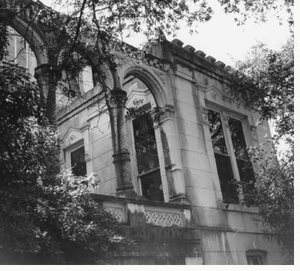

Keeping the original structure as the front of the home, a rear three-story L-shaped wing of stuccoed brick walls with a mansard roof was added facing Sixteenth Street. An octagonal, four-story tower with Gothic details and crenulation joined the old structure and new addition on the northwest corner, giving the home a castle-like appearance. The original hipped roof was embellished with gabled dormers.

On the east side, a two-story addition provided an outdoor terrace with cement balustrade. Its flat deck roof had a terne metal covering. The porch was constructed as a “ruin” carefully covered with moss. This romanticized style, known as “pleasing decay,” was highly popular with Victorians.

Now totaling an impressive 37 rooms, the home featured massive front doors, double parlors, several stained glass windows, a skylight, elaborately detailed walnut newel posts and balustrades, and a winding, wood staircase leading from the first floor to an exit at the captain’s walk on the roof. The walnut-paneled dining room showcased a beautiful, handcarved buffet, and a carved fish net chandelier mounting. A stunning 27 fireplaces populated the main rooms of the

home, each with a marble mantle and European tile hearth. One even had a secret panel for storing valuables - very castlelike, indeed.

Similar aesthetics were provided to the outdoor spaces with the addition of six porches, a stone piazza, and a “ruins” garden after the style of the day.

The 1890s additions have occasionally been attributed to Nicholas Clayton, but no proof exists of this. The theory was based on characteristics such as the detailing of the home’s bay windows.

Heidenheimer’s last project for his beloved Castle was the construction of a conservatory in March 1890. On February 22, 1891, he passed away from complications after surgery. His pallbearers were among Galveston’s most prominent citizens, including Julius Runge, H.M. Trueheart, I. Lovenberg, H. Marwitz, and J. Sonnenthiel. The illustrious Rabbi Cohen performed his eulogy at the funeral, which took place in the home.

Though Samson left a generous sum and the bulk of his $150,000 estate to his wife, his family took her to court and won possession of the Castle.

The castle remained in the Heidenheimer family for the remainder of the 19th century with Abraham, Isaac, Moses, David, or S. Mackay Heidenheimer either being listed as the owner or paying taxes at various times.

The home was not raised during the grade raising that took place on the island between 1903 and 1905. The first of the four floors became a basement, with fill being laid close to the building. Wells were dug to clear the lower level windows and a small flight of steps was installed to reach the front door.

The family used the home as a boarding house for the next two decades, and the property subsequently suffered neglect.

In 1936 the Castle left the Heidenheimer family, when it sold to W. I. N. Hammons for $2,500 and became a rest home. Hammons then sold it to Raphael B. Munvine, but in the late-1930s, it remained vacant.

Reported in poor condition with many of the fireplaces being covered over time, it operated as a rooming house during World War II .

James L. Koroneck made repairs to the Castle after the war in 1946, after which it once again operated as an apartment boarding house until 1954. Most of the 11 apartments had private baths, and the total monthly income from tenants was $428, approximately $4,470 today.

In 1954 and 1955, the home was successively owned by Robert F. Wilburn, a patrolman for the Seafarer’s International Union, and John E. Gray who operated it as a rooming house, mostly for sailors.

The Castle’s savior appeared in the form of Charlotte Ellen Warner, who was determined to bring back the Castle’s dignity and original beauty.

She purchased the home in 1962, and moved into it with her seaman husband Kenith and daughter Ellen Kay. They operated it as a rooming house while painstakingly restoring the property room by room.

She was instrumental in bringing attention back to Heidenheimer Castle by allowing inclusion of her home on a local tour just two years later, while restoration was still in progress. Her eight-yearold daughter Ellen Kay took great pride in helping to show visitors around, and regaled them with the story of how her mother had discovered a box of seashells hidden inside the ceiling.

In 1965, workmen digging in search of sewer pipes in the backyard uncovered a rusty, old safe, which was pried open and discovered to be empty. It had been buried just below the surface of an old brick patio.

Though no one knew how it came to be there or to which owner it had once belonged, the decision was made to leave it in place.

Restoration of the Castle and it’s grounds continued over the next couple of years. Unfortunately in 1968, Kenith passed away and the immense home became a challenge to maintain and restore for Charlotte.

One Saturday night in November 1973 while Charlotte was in St. Mary’s hospital recovering from surgery, the police department received an anxious call from a neighbor of the Heidenheimer Castle, reporting that juveniles were carrying some of the house’s contents away. Just a few hours later, the grand structure was engulfed by fire. Firemen battled the flames for hours, but in the end most of the furnishings and contents of the stone structure were destroyed, and the building was heavily damaged.

Charlotte decided to sell the Castle and J. E. Cooper, Jr. of Texas City purchased the partially destroyed home the following May with the intention of restoring the structure, but he was transferred by his employer before that came to be.

An attempt to auction off the home was made, but no bids were received. Cooper delayed demolition to provide an opportunity for late bidders.

The estate auction of Cooper and his wife in September 1974 listed numerous household items from the Castle, including a cherry wood settee, matching chair, two oak chests, cypress shutters, newel posts, and a stairway handrail.

Soon after the estate auction, the property was sold in October 1974 for $17,500. What remained of the Heidenheimer Castle was dismantled and salvaged architectural elements were sold off piece by piece. The Castle was torn down in 1975.

Not long after the Castle had been razed, Peter Brink, the Executive Director of the Galveston Historical Foundation at the time, approached Island native E. Douglas McLeod about purchasing the site and developing a residential project that would conform with the historical structures of the area.

McLeod agreed to purchase the former Heidenheimer property. Working closely with GHF andrenowned Houston architect Dean Robert H. Timme, McLeod designed a plan to develop six condominiums (now called The Heidenheimer Condominiums), which were completed in 1977.

In some ways the Castle still lives on. When the 1858 Hendley Building on The Strand was being restored in 1979, floor wood from the Heidenheimer Castle was used to replace damaged floorboards.