This month marks a milestone—the 120th anniversary

of The Great Storm of 1900. Which also means that

120 years-worth of history has been written about it,

and almost all of it is about Galveston. But why would it not

be?

This month marks a milestone—the 120th anniversary

of The Great Storm of 1900. Which also means that

120 years-worth of history has been written about it,

and almost all of it is about Galveston. But why would it not

be?

Roughly one in six residents were killed, many of whom

survived the storm itself but expired unable to free

themselves from the debris. One in four were left homeless,

1,900 acres of developed land were scraped clean by an

enraged Gulf, and the conservatively estimated $17 million

in damage equates to 25 times that amount today.

Nevertheless, a storm large enough to do that much

damage to one city was certainly large enough to impact

more than one. Nearby cities such as Alvin, Angleton,

Brazoria, El Campo, Pearland, Richmond, Alta Loma, and

Chenango suffered complete or near-complete destruction.

Death tolls and property losses were numerically lower

due to sparser populations and only rural development,

but the discrepancies lessen considerably when measured

proportionately to Galveston as a thriving urban metropolis

of the time. Houston, only marginally developed at this

point, still assumed nearly $250,000 in damages fifty miles

away from the center of the storm.

Numbers and statistics, however, only calculate the

quantifiable. The human experience of living through such

a monolith storm cannot be measured nor compared. The

immense terror of rising water, engulfing tides, hammering

rain, and riotous winds was universal.

If Shakespeare had lived on the Texas coast, his famous

line might have read, “hell hath no fury like Mother Nature.”

So potent, so all-consuming was this experience that a

frightened Sicilian immigrant in Houston made a promise

that has been kept by his family for well over a century.

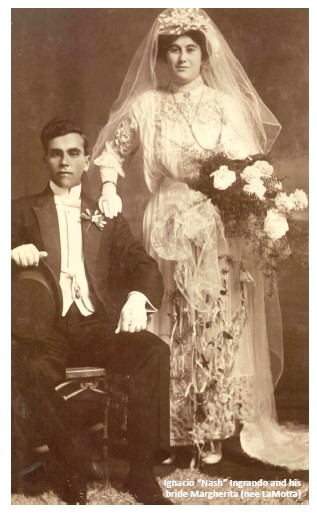

Ignacio “Nash” Ingrando immigrated to the U.S. through

New Orleans in 1888 at the age of 22. He traveled with his

wife Margherita LaMotta Ingrando, his infant daughter,

and two-year-old son. Eventually, they made their way to

Houston with several other extended family members.

Nash opened a grocery store on the corner of McKinney

and Sampson, and he and his family lived for a time on the

second floor. By the time the 1900 storm struck the Texas

coast, Nash and Margherita’s family had grown by two more

daughters, and they had moved to a home at Jackson and

Chenevert Streets.

Inside this house, Ignacio, Margherita, and their four

children Rosie, Frank, Jenny, and Annie clung to each other

on that fateful September Saturday. Outside, the howl of

100 mph winds was punctuated with the sounds of breaking

glass, broken tree branches scraping across their windows,

electrical poles toppling into their street, and shingles

ripping from the rooftops.

Desperate and fearful for his family, Ignacio prayed, “Oh

Blessed Mother, if you save my family, I’ll have a mass said

in your honor every year.”

The Ingrando family escaped unscathed, as did all

Houstonians save two, but the favorable odds did not

diminish Ignacio’s appreciation. Following the storm, his

grocery business thrived, and he continued to hold the

mass every year until his death in 1929. His son Frank then

took it over, then it was passed on to the grandchildren,

and then the great-grandchildren. Every year for 119 years,

the Ingrando family has kept Ignacio’s sacred vow, and the

tradition continues in 2020.

Myrna Sanders, the great-granddaughter of Rosie

Ingrando Bilao, says that time has not diminished the

family’s commitment to their patriarch’s promise. “We are

not always able to have it on the exact day, September

8, sometimes it is the Sunday before or after, and not

everyone can come every year,” she says.

“But for the most part, everyone tries to keep that date

open. It is very special to all of us. In 2000 for the 100th

anniversary, all the descendants came.”

This year, an in-person event is not possible because of

the pandemic, but the family was insistent that it continue

in any way possible. “I spoke to my cousin who organizes it

now, and she said, ‘there is no way I am going to not do it,”

Myrna shares.

And so, the service will be held virtually to avoid a large

gathering, but the virtual format will also allow family

members to attend who might not have been able to travel

regardless.

The mass includes scripture readings, a sermon, and

the singing of hymns. In the earlier years and in honor of

Galveston, the family would sing “Queen of the Waves.”

Legend holds that this hymn was sung by the nuns of St.

Mary’s Orphanage to their wards as they succumbed to the

storm. The lyrics hauntingly echo Ignacio’s prayer, revealing

that the outpouring of tragedy is not bound by time or

location.

“Help, then sweet Queen, in our exceeding danger, by thy

seven griefs, in pity Lady save; think of the babe that slept

within the manger and help us now, dear Lady of the Wave.”