Today’s visitors to Galveston beaches think nothing of walking down the shore in a swimsuit or jumping playfully into the water. A hundred years ago it was quite a different experience.

In 1860, wading in the gulf began to increase in popularity, influenced heavily by travelers who had experienced beach bathing in their travels to Europe. By the Georgian and Victorian eras, rolling bath houses, or bathing machines, were copied from styles seen abroad.

Bathing in the waters was thought to have a therapeutic effect and evolved from the long-held practice of visiting spas and springs for their beneficial waters. This custom became more popular as railways offered residents in surrounding communities the opportunity to visit the beach for the day.

At that time, most people did not own their own swimwear and rented the apparel when they visited a beach. Large bath houses here on the island, such as Murdoch’s, offered private dressing rooms.

However, after changing clothes, guests needed to walk down stairs or a public ramp to reach the beach before entering the water. Rolling bath houses had the distinct advantage of offering more privacy to modest bathers.

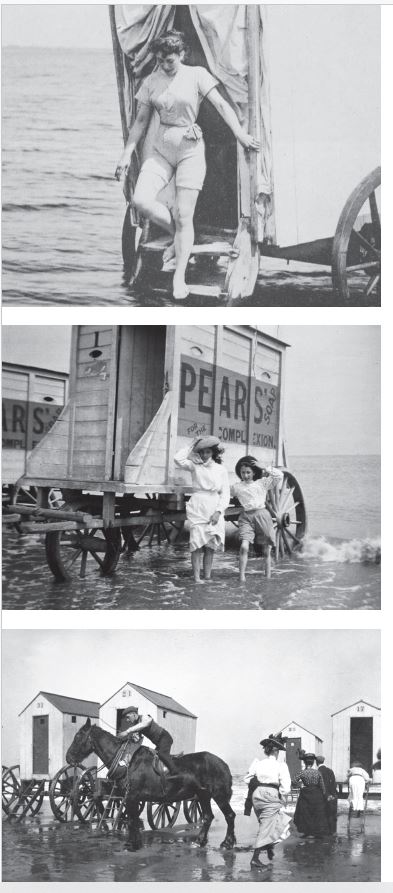

The houses, or rooms, were made mostly of wood with a door on each end and set on four wheels. Customers would enter the structure and, as they were changing into their bathing costumes, the house would be pulled to the waterfront with its front wheels in the water by mule or donkey.

Interiors of the houses were sparse, with only a bench to sit on while changing clothes and perhaps a hook or two for towels and clothing. Holes were drilled into the floor to allow the tracked-in water and sand to drain out. There might also be a small mirror on one wall so that guests could check if they were acceptably covered.

Guests would then exit out of the back door, directly into the water. Some rolling houses provided canvas hoods which could be lowered, like an awning, to shield ladies from prying eyes as they exited.

Ropes were tied on posts through the water and often to the bath houses so that inexperienced swimmers could grasp them for safety.

The houses had the added extra benefit of providing a safe, dry place to leave clothing and other belongings.

Bathing in itself was more akin to wading, as many visitors to the beach did not know how to swim. In some locations, the roller bath houses had female attendants known as dippers who would help women out of the water as their heavy woolen bathing attire often added 20 pounds of weight when wet.

When the bather was finished enjoying the water and had redressed into their street-appropriate clothing, they would raise a small flag on the roller house that would signal an attendant that it was time to pull them back onto dry land.

They became so popular that Delft roller bath houses were sold as Christmas gifts at a local department store in December 1896.

Even with the modesty of knee-to-neck swimwear and the use of bathing houses, American bathers were decidedly less modest than their European counterparts who would never consider mixed bathing, which referred to men and women enjoying the surf at the same time and place.

Regulations about modest swimwear were not necessary at first, although nude surf bathing was common for men after dark. As interpretations of conventional modesty evolved, swimsuit fashions became bolder.

Regulations about modest swimwear were not necessary at first, although nude surf bathing was common for men after dark. As interpretations of conventional modesty evolved, swimsuit fashions became bolder.

Galvestonian James Doyle, an Irish immigrant, operated roller beach houses beginning in 1896 from the corner of 25th Street and the beach. After two years, he sold the business to John M. O’Rourke, a general contractor who named his business Union Roller Bath Houses.

O’Rourke moved the mobile bath houses to the northwest corner of 23rd Street and the beach. He lost the entire business during the 1900 Storm but was rebuilding it within two weeks of the hurricane.

Once the Seawall was constructed, the businessman petitioned city commissioners for permission to build a platform for the roller houses on the south side of the wall between 23rd and 24th streets. Without the platform, it was necessary to lower and raise the structures over the Seawall for use each day.

At that time, the city was concerned about bath houses or any other structures on the beach that might obstruct traffic and bathers and his plea was denied the following year. This obstacle made his roller bath house venture virtually inoperable, and he abandoned the business in 1905. Ironically, O’Rourke was the contractor in charge of building the Seawall.

Dr. John B. Haden, a local professor of ophthalmology at the University of Texas, decided to try his luck in the roller bath house business in 1905 but took a different approach. He purchased all of the existing roller bath houses and a considerable amount of property at the southern foot of 57th Street.

There he opened Palm Beach Garden, a waterfront attraction that controlled the beach fronting its property. Fifty-Seventh Street was designated as the end of the car line at the time, so there would be no accusations of obstructing traffic.

He ordered several hundred California palm trees to be planted on the property, which now extends into the Denver Resurvey area.

In July 1906, Haden opened a pavilion with a restaurant and café, and placed a number of roller houses on the beach for guests. He hired Joseph McNamara to manage the property, so it would not interfere with his medical practice. He owned the venture through 1907.

By the 1920s, use of the cumbersome rolling bath houses disappeared from Galveston beaches, and into tales of the charming past.