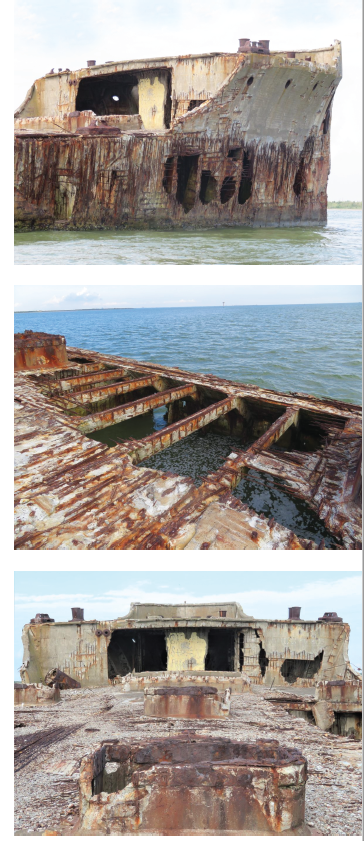

One of Galveston’s most famous landmarks is not on land. The remnants of a concrete ship from World War I rest on the Pelican Flats just off the coast of the port city, partially submerged in Galveston Bay. Passengers of the Port Bolivar ferry pass the site each day, amazed by the size and history of the mysterious-looking maritime skeleton.

When you think of shipbuilding materials, concrete certainly is not the first thing that comes to mind. Galveston is one of the few places where visitors can view a relic of a time when the dream of concrete ships became a reality.

Steel shortages during World War I left engineers in search of alternative materials to build ships for the war effort. Great Britain had successfully constructed smaller floating boats and platforms from concrete, but many sailors referred to them as "floating tombstones" and did not like to serve on them.

President Woodrow Wilson approved the construction of 24 concrete freight ships, the largest of which was the SS Selma.

The first 12 were built by F. F. Ley & Company in Mobile, Alabama at a total cost of 50 million dollars. Selma, the largest of the ships, was named in honor of another Alabama town in thanks for conducting a successful Liberty Loan Drive during the war.

The ship was 431 feet long, 54 feet wide, weighed 7,500 tons and was the most expensive of the ships with an estimated construction cost of three million dollars. Designed with two decks, two masts, and a round stern, she had a four-inch thick hull and five-inch thick bottom.

A newly developed shale aggregate expanded in rotary kilns resulted in a lightweight structural concrete deemed ideal for ship construction. The designs were based on the plans of steel ships, but although the mixture was lighter than most cement it was still much heavier and more difficult to manipulate than steel.

The structure of Selma required 2,660 cubic yards of concrete reinforced with 1,500 tons of smooth steel bars. The combination caused her to float low in the water when fully loaded, but she did float. Her displacement weight was 13,000 tons.

The massive ship was launched on June 28, 1919. Ironically, this also happened to be the same day Germany signed the Treaty of Versailles, ending the war.

Selma never entered the war and was instead placed into service as an oil tanker in the Gulf of Mexico. She made three recorded trips and visited multiple ports before a navigational miscalculation ended her career.

While the vessel was coming into port in Tampico, Mexico on May 11, 1920, her captain got off course and drove her over a jetty. The resulting 60-foot crack punctured her hull and caused the holds to fill with water.

Planks were nailed to the bottom as a temporary patch while 14,000 barrels of her original cargo remained aboard. After she was bailed out and compressed air was pumped into her forward compartments, she was slowly towed back to Galveston by tugs named Resolute and Barranca.

Selma arrived at Pier 35 on August 20 seeking permanent repairs, originally estimated to take three months. But because local dry dock crews had no experience working with the unique materials involved, she was moved from one shipyard to the next for eighteen months in search of a solution. Compressed air kept the ship barely afloat and maintenance costs skyrocketed.

The United States Shipping Board eventually decided to cut their losses and ordered the Selma to her grave. It was decided that she would be scuttled in an out of the way section of the harbor, off Pelican Island’s eastern shore.

A trench 1,500 feet long and 25 feet deep was dug about 1,200 yards north northwest of the present-day Seawolf Park, where two other maritime treasures, the USS Stewart and the USS Cavalla are permanently displayed.

After stripping her of any valuable equipment, including her engine, two tugboats attempted to drag her to final resting place. But the immense ship refused to accept her demise easily and failed to budge.

More tugboats were called in and after a dozen of them finally got Selma moving, she fouled the line of a dredge and became mired in the mud.

After two weeks and half a dozen attempts, the tugs laid the concrete ship into place on March 9, 1922. The depth of the trench left the hull partly submerged, but low enough that rough seas washed over her.

In the years since her abandonment, numerous enterprising parties have attempted to give the ship a sort of second life. Plans to convert the hulk for use as a fishing pier, tavern, dance hall, pleasure resort, hotel, oyster farm, and other ambitious projects have all made waves in the planning stages but ultimately sunk into financial impossibilities.

A succession of owners has included a hermit who lived on board and a businessman who saw the concrete ship as an investment.

At different times in her history, the scuttled ship has been a hideout to modern day pirates and smugglers. Older locals tell stories about bootleggers who stored their merchandise in the holds of the ship during prohibition.

Another tale about the ship is fascinating enough to be a legend but seems to have a strong basis in fact. F. W. Mullings, owner of the East End Radio Shop, was a radio directional finder adjuster for the Radiomarine Corporation during World War II.

In March of 1942 a vessel was late coming from the Port of Houston, and he and a companion boarded the supposedly deserted Selma to radio from that location. They encountered a man whom neither of them recognized, eating a lavish breakfast. He failed to offer an explanation for his presence or how he was able to acquire such a meal on a derelict ship and kept to himself.

The pair suspected the man of being an enemy spy who was relaying reports of ship movements to the Nazi submarines that had been spotted in the gulf. Though naval intelligence never confirmed the findings of their investigation, the man disappeared and the torpedoing in the area came to an abrupt halt afterward. No information was given to the public about the matter due to wartime censorship, but word-of-mouth quickly spread the story across the island.

During the era of Texas Attorney General Will Wilson’s raids on gaming dens in Galveston in the 1950s, confiscated gambling equipment, including 350 slot machines found hidden in an old underground bunker at Fort Travis, were dumped in the waters surrounding the ship.

The port authorities took issue with the action, and both parties agreed to cease disposing of the one-armed bandits in the waterways.

In 1953 and 1955, the vessel became the subject of scientific research by Washington, D. C. after locals reported their belief that the concrete of the ship had actually grown stronger over time.

Despite the long exposure to marine elements, core samples revealed that the concrete below the mean water line had increased in strength by 57 percent from the time it was poured in 1919, and the interior rib area had strengthened by more than 45 percent.

Despite the long exposure to marine elements, core samples revealed that the concrete below the mean water line had increased in strength by 57 percent from the time it was poured in 1919, and the interior rib area had strengthened by more than 45 percent.

The steel reinforcing bars also showed little evidence of rusting, and almost no sign of corrosion despite the salt air environment. It was attributed to the high bond of aggregate to mortar formula, which reduced stress on the steel while completely sealing it.

The materials were reviewed again in 1980 when new samples were tested. Waterline and submerged core samples at that time showed little if any deterioration. Engineers estimated that the concrete reached its peak strength in 1975.

Despite these findings Selma is crumbling, mostly on deck areas subject to vandalism and rotting wood supports.

In 1992, a retired editor of the Houston Chronicle and Galveston Daily News named A. Pat Daniels purchased the ship. His proprietorship of the vessel was the greatest gift the World War I relic could receive.

Daniels’ devotion to the ship resulted in it being recognized with a Texas State Historical Marker, being placed on the National Register of Historic Places, named a Texas State Archaeological Landmark by the Texas Antiquities Committee and even receiving a designation as the Official Flagship of the Texas Army.

Each year, Daniels threw a birthday party for Selma, though he insisted on having the festivities on land to avoid possible attacks by “sharks, whales, pirates and sea-sickness.”

When Daniels passed away in 2011, he left the corporation that now owns the ship in the care of Admiral Bill Cox and his wife Edna, who had played a major role in Selma’s story. After their passing, their son Ken stepped up to the helm to uphold the traditions established in recent years.

Years of marine growth along the hull of the historic vessel now attract a variety of fish, making the surrounding waters a haven for fishermen who anchor within a few hundred feet of the relic.

The ship is private property and trespassers will only encounter the danger of gaping holes in the deck and crumbling supports. One misstep could prove disastrous.

Selma is likely to remain in the waters off Pelican Island for generations to come, a curiosity whose flooded hulls are filled with the stories and legends that surround her.

Selma’s Second Career

The concrete ship had an “illustrious” second career serving as, among other things, a storage for explosives in 1926 and also as a work staging area by Oil Exploration Company in 1928 (local residents complained Selma was an eyesore and suggested using the dynamite on the vessel).

A most interesting side note on Selma was the use of the steamer for the disposal of bootleg liquor confiscated by U.S. Customs Inspectors during Prohibition. Galveston’s strategic location made it ideal as a major entry point for smuggled liquor.

On four occasions Selma was used for the destruction of seized liquor cargoes, the last two “parties” occurred in the fall of 1926. On September 29 over 11,000 bottles of liquor, worth an estimated $91,000 (street value), were taken from the appraiser’s store to Pier 22 where they were transported by barge to Selma and broken up in the vessel’s hold. The following week, the contraband cargos of the vessels Island Home and Rosalie M. were also transferred to Selma for destruction.

The combined cargos from the two vessels amounted to approximately 2,000 cases of liquor worth almost $120,000. The total street value of all the liquor destroyed on Selma was nearly $1,000,000 and excluded all the liquor returned to Havana.

Courtesy of maritimetexas.net