Present-day naysayers often dismiss modern sports as frivolous, gratuitous, and even ridiculous, but there is a reason why sports fans cling enthusiastically to what is ultimately “just a game.” Beyond the million-dollar contracts, billion-dollar stadiums, and athletes branded with the latest fashion labels, exists ironically—just the game.

In the case of baseball, it is a game that has been dubbed the national pastime not because of its professional presence (only a third of U.S. states, 17 to be exact, have professional teams), but because for nearly two centuries, it has been played on vacant lots in every city in the nation—Galveston included. Yet far more than hosting Saturdays on the sandlot and high school rivalries, the unsinkable island city has born witness to a history of struggles, setbacks, triumphs, and traditions that have made professional baseball America’s sweetheart of sports.

General Abner Doubleday has been both credited and discredited as the father of baseball, allegedly creating the game in New York in the 1830s, long before he led Union troops during the Civil War. Less disputed is the claim that the General brought baseball to the island, even though some early accounts indicate that informal games were played prior to his arrival.

In 1865, as the ill-fated Confederacy slowly acquiesced to their defeat, Union soldiers were stationed in Galveston to begin the process of Reconstruction in one of the country’s premiere port cities. The “damyankees” suggested a match of a sport widely known already in the north as “base ball.” Regiments picked teams, and the first game on the island was played north of the Ursuline Convent (25th and Avenue N, demolished), at a time when the land was wide-open salt marsh prairie.

At the game’s conclusion, local residents are reported to have “pshaw-ed” the troops as having stolen their game of town ball. A predecessor to “base ball” (originally spelled as two words), town ball was quite similar to the new game with three bases (or “sacks”), a pitcher, and a catcher. The town’s reaction to baseball indicates pre-established affection for a game that easily and quickly transferred onto baseball.

Doubleday’s arrival to Galveston in 1866 did, however, certainly lead to the first recorded game in the state and subsequently the first official baseball diamond drawn on Texas soil. On January 8, 1867, the Galveston Daily News announced and advocated for plans to establish a permanent baseball club in the city.

Ten days later, the News followed up with a report that the grounds for the club had been chosen and the time set for the island’s first organized baseball game. On January 18 at 3pm, the lot in front of the City Hospital (present-day John Sealy Hospital), would host the first exhibition of the Galveston Base Ball Club.

Attesting to the appropriateness of the game, the News specifically encouraged ladies to attend, remarking that “in the North, a lady is not considered fashionable unless she attends performances of this character.”

The organization of baseball in Galveston also met with some minor opposition from concerned residents who protested to the Galveston Flakes Daily Bulletin that the Texas climate was not suited to the game.

“Base ball (sic) is a game that exposes the player to sun and to brief, but violent exertion.” These factors were by contrast, “healthful in colder climates.” Their argument concluded by promoting gymnastics training, stating that “a covered gymnasium will…better serve the purpose of aspiring athletes than the ball field.”

These protestations were largely ignored, and the popularity of the Galveston game spread rapidly up to Houston and every small town in between, undoubtedly assisted by the organizational efforts of Doubleday whose enthusiasm for the game would later travel as far as San Antonio and into West Texas. As a result, the first inter-city matchup in Texas was played mere months after the first Galveston exhibition. On April 21, 1867, the Stonewalls of Houston annihilated the Galveston Robert E. Lees with a score of 35-2.

Over the next twenty years, up until the introduction of play for pay baseball in 1888, amateur games and ball clubs sprang up across the city. These early clubs represented trades, unions, social clubs, and the like, with names like the Drummers, Major Burbank’s Artillery, The News, Turf Association, Galveston Stars, Santa Fe, Athletics, Island Juniors, Bricklayers, Cornice Makers, Invincibles, and Western Union. Out of dozens of teams, two emerged as the local favorites.

The first were the Flyaways, the first African American team in Galveston whose notable reputation persisted despite the country’s entrance into a century of segregation following the war. The other was the Island City Club formed by local businessman Jeff Tiernan, owner of a cigar shop and popular baseball hangout located at 23rd and Market Street. Tiernan formed the Island City Club after a player on a team he supported was intentionally injured.

Determined to extract justice from the peaceful end of the baseball bat, he sent scouts to New Orleans to secure big-time talent. His plan also included financing the construction of a ballpark at 23rd and Avenue Q, later called Beach Park.

There the Island City Club hosted other Galveston teams as well as clubs from Houston, Denison, Palestine, and Fort Worth. Peaking in their final season, Tiernan’s club won 35 straight games in 1887.

Fans of the Island City Club made history as well, by initiating what would eventually become the seventh inning stretch. After someone inadvertently discovered that statistically, the club scored most of their runs during the seventh inning, fans decided to stand for the duration of the bottom half of the inning. It soon became a tradition for all Texas League teams and later extended throughout all of baseball.

The year following the Island City’s unprecedented winning streak, Galveston became a founding member of the Texas League, the state’s first professional baseball league. Following the 1876 formation of the enduring National League (presently the oldest league in professional sports), and prior to a time when interstate travel was efficient or even feasible, states and regions across the country formed an array of professional leagues.

However, unlike the unquestionable permanence of today’s American and National Leagues which were unified to form the MLB in the late 1990s, the financial and logistical woes of early owners and teams meant that the Texas League was forced to reorganize after every season depending on which teams folded or were sold.

Thereby, the island’s inaugural professional team, called the Galveston Giants, were disbanded after their first season in 1888. The torch was then passed to the Galveston Sandcrabs, a team built around members of the famed Island City Club. The Sandcrabs were crowned Texas League Champions in 1890, but by 1892, the Texas League was completely defunct.

Fortunately, in 1895, both the Texas League and the Sandcrabs were resurrected, the latter by W.L. “Farmer” Works. He needed financial assistance almost immediately and solicited the help of George B. Dermody who owned the team through its 1896 season.

The Sandcrabs played at Beach Park prior to the construction of the seawall. The outfield fence was therefore situated right on the beach, and this precarious location sometimes led to humor and high drama on the ball field.

During a game against a Houston team that happened to coincide with high tide, a Galveston player hit a home run only to be surprised at home plate by a catcher holding a saltwater-logged baseball. The tide had washed the ball back under the fence, and an ambitious outfielder scooped it up and hurled it homeward. A vehement argument ensued, but the umpire eventually ruled in favor of Galveston who went on to win the game.

In 1897, the southern teams of the Texas League including Galveston, Houston, San Antonio, and Beaumont, made a collective decision to eliminate the expense and inconvenience of traveling to the northern ball clubs in Dallas, Fort Worth, and Sherman. They split off and formed the South Texas League.

After winning the South Texas League championship in 1897 and 1899, the Sandcrabs took a forced, four-year hiatus before returning to the southern league in 1903. The next year, the Sandcrabs moved their designated field to Auditorium Park within the grounds of Menard Park (27th and Seawall, present-day McGuire Dent Recreation Center) and finished the season with another championship—the last trophy Galveston would claim for thirty years.

One member of the 1904 team went on to make baseball history in 1910 when he executed an unassisted triple play. Third sacker (third baseman) Roy Aiken caught a line drive, stepped on the third sack before the runner at third could tag up, then turned and tagged the runner coming from second who presumably took off at the crack of the bat, not realizing that Aiken had fielded the ball.

Yet another Texas legend honed his career on a Galveston ballfield. Billy Disch, outfielder for the Sandcrabs in 1906, would later win numerous championship titles as the head coach of the University of Texas baseball team. At the helm of the UT team from 1911-1939, Disch finished with a spectacular career record of 513-180 (.740) over thirty seasons.

In 1907, the North and South Texas Leagues permanently merged, and the Sandcrabs played a lackluster five seasons before being disbanded and replaced by the Galveston Pirates. The Pirates played continuously from 1913-1921 except for the 1918 season which was canceled due to World War I. Their home turf was Pirate Field from 1915-1920 (location unknown, possibly a renamed Auditorium Park), but moved to Gulfview Park at 2802 Avenue R ½ for their final season in 1921.

The Galveston Sandcrabs were then reinvented again in 1922, but the third incarnation only lasted until the 1924 season, after which they were sold to Waco for $22,500. After enduring five long years without professional baseball, Galveston sports-lovers discovered a savior in island magnate Shearn Moody Sr., son of W.L. Moody Jr., and grandson of Colonel W.L. Moody.

The Galveston Sandcrabs were then reinvented again in 1922, but the third incarnation only lasted until the 1924 season, after which they were sold to Waco for $22,500. After enduring five long years without professional baseball, Galveston sports-lovers discovered a savior in island magnate Shearn Moody Sr., son of W.L. Moody Jr., and grandson of Colonel W.L. Moody.

With a deep appreciation for Galveston and a sincere belief in the city’s potential to become a preeminent entertainment destination of the U.S., Shearn fittingly bought back the Waco club, the Waco Cubs, and returned them to their island home in 1931. Today, Shearn’s team is perhaps the most well-known in Galveston baseball history—the Galveston Buccaneers, named after the Moody’s famous Buccaneer Hotel at 23rd and Seawall Boulevard (demolished).

After the Bucs recorded a win-loss ratio far below .500 in their first two seasons, Shearn replaced manager Del Pratt with Billy Webb. Webb would deliver to Galveston its last Texas League Championship as the fitting conclusion to a spectacular 1934 season. Yet far greater than the impact of his team was Shearn Moody’s construction of Moody Stadium at 5108 Winnie.

Built of steel, concrete, and cypress, the 8,000-seat stadium was situated on Winnie Street, spanning ten acres between 51st and 53rd Streets. It was fully lighted, making it one of the first stadiums in Texas to host night games. A large metal fence surrounding the perimeter of the ballfield sought to eliminate non-paying spectators, long considered a nuisance by club owners who were desperately dependent on ticket sales for the survival of their teams.

The stadium was also one of the first to offer tiered ticket prices for box, reserved, grandstand, and bleacher seats, while the northwest corner of the stadium provided full-time shade during afternoon games.

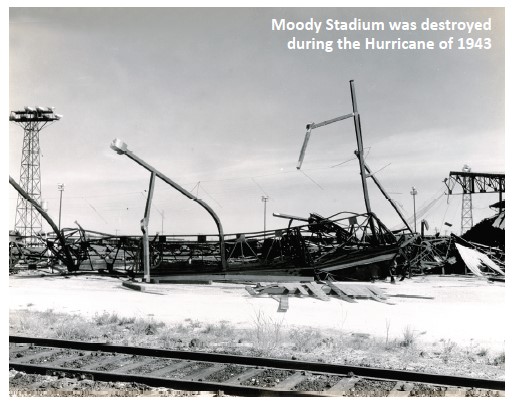

Following Shearn’s untimely death in 1936, Roy J. Kochler assumed control of the club from his estate. Unfortunately, the absence of Shearn’s unbridled enthusiasm and genuine love for his team was palpable and inescapable, and the Buccaneers were regrettably sold to Shreveport, Louisiana, before the conclusion of the 1937 season. Six years later, the Hurricane of 1943 wreaked irreparable damage upon Moody Stadium, and it was soon demolished.

Galveston’s final foray into the professional baseball circuit came with the inception of the Galveston White Caps in 1950 as part of the newly formed Gulf Coast League. In 1953, the White Caps gifted Galveston with its final championship, after which the Gulf Coast League folded. They played for two more years in the Big State League but were finally disbanded after the 1955 season.

Appropriately, their namesake carries on today with the Galveston College White Caps baseball and softball teams—a fitting tribute and the last vestiges of the island’s 150-year baseball tradition.