Part 1: The Mystery of

Coppini’s Famous Statue

In October 1900 just a month after the Great Storm,

newspaperman William Randolph Hearst organized

a benefit for the Galveston orphans to be held at the

Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York. Artists and sculptors

were invited to submit artwork to be auctioned during

the benefit, and renowned sculptor Pompeo Luigi Coppini

donated a small maquette of a design he titled the “Victims

of the Galveston Flood.”

The high bid for his piece brought him to the attention of

Texas society, and within a year the sculptor moved to San

Antonio to pursue commissions. When the opportunity to

create a sculpture for the St. Louis World’s Fair Palace of

Fine Arts presented itself, Coppini’s heart was drawn back to

the “Victims” design that had been so popular three years

earlier.

After initial sketches that outlined a distraught mother

with her children draped across her lap, he created a lifesize

plaster of a nude mother and children portraying the

victims as having their clothing ripped away by the force of

the storm, much as many had been in reality.

His third incarnation was a realistic, 11-foot-tall plaster

portrayal of a female survivor holding her deceased infant

and standing with a little girl whose arms wrapped around

the woman’s waist, head pressed against her mother. The

group stood upon a precarious mound of debris from which

a lone arm reached up in a last grasp toward rescue.

The artist held an open exhibition of the piece in his

small San Antonio studio in early 1904, and more than one

thousand people passed through the doors. The solemn

crowd included art lovers, storm survivors, and others who

had lost friends and loved ones in the tragedy, and many

became tearful at the sight of the statue.

Once the visitors returned home, Coppini sat on the steps

of his studio and wept, overcome with emotion at the

response.

THE WORLD’S FAIR

“Victims” was shipped to St. Louis for the fair in 1904.

Unfortunately, the statue was misplaced when it arrived on

the dock. It was discovered in cold storage labeled as “fruit”

two weeks later but had missed the deadline for display in the Palace of Fine Arts competition.

Fair organizers made the decision to display the piece

in the less prestigious Texas State Building, especially

disheartening since Coppini was hopeful that recognition of

the work during the fair might result in a commission of a

bronze version by Galveston leaders.

Providing further disappointment, Galvestonians thought

that the portrayal was “too painful” to display in their city

so soon after the tragedy and declined to fund its casting.

UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS

The emotional figures returned to Coppini’s San Antonio

studio after the World’s Fair, where they remained for ten

years. During those years, the artist created numerous art

pieces still admired around Texas, including work for Major

George Littlefield who was involved with the University

of Texas. When the artist decided to move his studio to

Chicago, he offered to donate 24 of his works, including

“Victims,” to the university rather than moving them across

the country.

Despite not having a building in which to exhibit the

pieces, university officials accepted the gift with a promise

to put them on display. They arrived on campus in May

1914.The crated statues were stored in the chemistry

building in a storeroom beneath a lecture hall before being

stored in basement corridors in the east end of Old Main,

now the site of the UT Tower.

Students from the Longhorn Magazine found the crates there

in 1918 and published an article demanding that they be

displayed as was originally promised, stating, “He has given the

University a princely gift. It must be admitted that we accorded

it but a beggarly reception.”

The statues were finally exhibited for five days in the

education building, now known as Sutton Hall, during the

Christmas season of 1919.

The plaster statues included busts of Jefferson Davis, A. S.

Johnston, General T. J. Jackson, and Robert E. Lee, executed for

the Confederate monument in Paris, Texas. Also included were

the studies for busts of Mark Hamburg the Russian pianist;

Lieutenant Richard Hobson; former Mayor A. P. Wooldridge

of Austin; Major G. W. Littlefield and Mrs. Rebecca Fisher.

Among the bas-reliefs were the central figure of General

Sam Houston and the accompanying allegorical figures of

History and Victory used for the Sam Houston Memorial

at Huntsville and “The Falling Trees” of the Falkenburg

Monument in Denver, Colorado. Also displayed were studio

pieces titled “Woman with Parasol” and “The American

Boy,” depicting Norvel Welsh Jr.The two grandest examples were displayed on the ground

floor of the building: the brave “Texas Pioneer” which

served as the plaster cast for the bronze that tops the

Independence Monument at Gonzales, and the “Victims of

the Galveston Flood.”

The only documentation of the display is a story in the 1920

UT Cactus yearbook, which states that there were “several

colossal figures in the basement which were too badly broken

to set up.” The brief exhibit was the last time “Victims” was

seen, seemingly vanishing without a trace.

That year Coppini was planning the Littlefield Fountain that

would be dedicated at UT ten years later after numerous

battles with the university concerning costs and redesigns

affecting his vision. It was offense added to the loss of his

statuaries, which enraged the artist. He occasionally even

referred to the pieces as having been “destroyed,” suggesting

vile actions by university representatives.

No mention was made in university publications about the

statuary until 1928, when ten of the portrait busts were found

on the third floor of Old Main. From then the trail runs cold.

A MYSTERY ENSUES

Artist Waldine Tauch, Coppini’s protégé, wrote a letter to the

president of the university in 1943 asking if he had located

“Victims.” He responded that he had not but promised to

conduct a search soon. It was the last communication from

him on the matter. Coppini also conducted searches for

the statuary, repeatedly contacting the university with no

response.

His 1949 autobiography From Dawn to Sunset mentions

his distress about the disappearances multiple times

complaining, “No one has been able to this day to give me

information as to their whereabouts.” The loss of “Victims

of the Galveston Flood” was particularly upsetting. “Who

could have been so naïve as to plan its destruction? Will I

ever forget such a crime?”

Coppini died in 1957 without ever learning the fate of his

missing works. Since his death, more than 80 individuals and

institutions have been involved in the attempt to solve the

mystery, but no definitive answers have been found.

The best-case scenario is that they are stored unnoticed

but safe, in an unsearched storage section of a building

on the UT campus, but theories abound. They include the

possibility that the statues may have been destroyed in a fire

in the chemistry building in 1927. If university administrators

were aware that the pieces were involved in the losses, they

declined to admit it to Coppini.

When Old Main (where the artwork was last displayed)

was torn down in the 1930s, its bricks were stored in a

nearby World War II era magnesium plant. Perhaps the

statues were shipped to the same location. That plant is

now the J. J. Pickle Research Center.

Another likelihood is that the plaster sculptures were

carelessly damaged or broken during moves around the

campus or maybe they are unwittingly dispersed across

the state, sitting in someone’s backyard. For now, the final

fate or current location of “Victims of the Galveston Flood”

remains unknown.

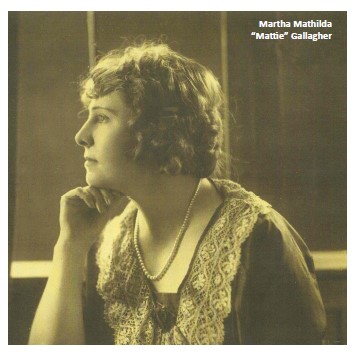

Part 2: Coppini’s Muse

Part 2: Coppini’s Muse

Many of the most beautiful works of art have been

created with the help of muses, and “Victims of

Galveston” was no exception. The vision for the

beautiful woman in this work did not come from Coppini’s

imagination, but from the appearance of an 18-year-old

model named Martha Mathilda “Mattie” Gallagher. Her

eight year old sister Bess posed for the portrayal of a

terrified girl clinging to her mother’s legs, and their niece

Fern served as inspiration for the drowned baby cradled in

Mattie’s arms.

Austin antique and art dealer James Powell is the great

nephew of Mattie and Bess, and knew them well. His

grandmother Estelle Powell, who was a sister to the two

models, even studied with Coppini.

Powell vividly remembers his Aunt Bess reminiscing with

him about how meticulously her mother had sewn the

seams and tucks at the bottom of the chemise she wore

while modeling for Coppini, wanting them to be perfect for

the artist. It is a detail that always draws his eye when he

sees photos of the sculpture.

In addition to her beauty, Mattie was a talented singer.

Powell says, “She studied music in New York, and she had

the same voice coach as Caruso. I’m told that when she

walked down the streets of New York, people would turn

around and look.” At one point she even co-wrote and

copyrighted a song with her brother Jules.

Mattie lived past the age of 100, and left behind a legacy of

beauty, talent, and an extraordinary personality.

Coppini published an autobiography titled From Dawn to

Sunset which included details about his works.

Coppini published an autobiography titled From Dawn to

Sunset which included details about his works.

“I actually have the book which he inscribed to [Mattie] with a lovely inscription in the front. On the page where

it shows the lost statue and says what year it was created,

she crossed the year out and made it 10 years later,” Powell

laughs. “At that time women were a bit more phobic about

having their true ages revealed.”

Reading from the autobiography, Powell proudly shares

a quote from Coppini. “In Austin I was often royally

entertained by many friends, and by friends of my friends.

But I must not fail to mention the Louis Reuter couple,

as Mrs. Reuter posed for my group of the ‘Victims of the

Galveston Flood’ when a girl... She was a daughter of

the large Gallagher family, all beautiful and very talented

children of a talented father who had written many worthy

poems.”

Coppini continued, “Mattie however had the most

beautiful, perfect and dramatic features I ever saw along

with an extraordinary talent for music and singing. My wife

and I were extremely fond of her, and I was invited to spend

a weekend at their new home in Rosedale Terrace. I had

not seen her for many years but she was still beautiful as a

matron and very happily married.”

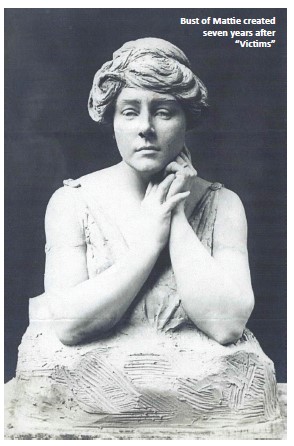

Powell has a photograph of Coppini standing in the

courtyard of her home during this visit, enjoying the view. A

bust of Mattie created seven years after “Victims” appears

in the background of photos of Coppini’s San Antonio

studios.

Mattie’s home on Rosedale Terrace in Austin’s Travis

Heights neighborhood is now in the United States Register

of Historic Places. At the time she lived there with her

husband, it was a social gathering place for the artistic

community. Among her many talents was writing poetry

like her father, so it is appropriate that the home was the

birthplace of the Austin Poetry Society.

“My aunt’s house, which used to be on a big piece of

land, is one of the most beautiful houses in Austin,” muses

Powell. “It’s a little Italianate villa with an incomparable

view.”

Powell holds out hope that the missing “Victims of the

Galveston Storm” his relatives posed for will some day be

found, although he suspects there may have been some

malice involved with the disappearance of the Coppini

statues from the University of Texas campus.

“I’ve been fascinated and mystified by the work’s

disappearance for 55 years. I’ve been asking people about it

at every opportunity.”

Powell remembers his grandmother Estelle, also a friend

of Coppini’s, telling him that Galveston’s leaders chose not

to pay to create a bronze version of the sculpture. “She said

she was told it was too painful a reminder, too realistic,” he

remarks.

Even more painful now is the loss of such a groundbreaking

work by a master sculptor.

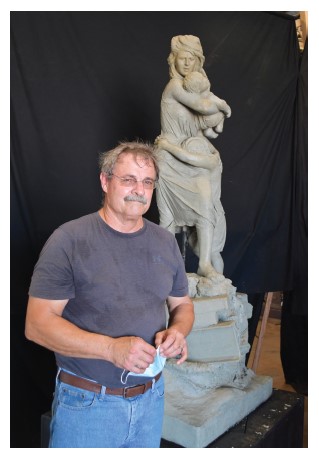

Part 3: Turning “victims”

into “Hope”

The lost 1904 statue of “Victims of the Galveston

Storm” by Pompeo Coppini has inspired a local artist

to create his own interpretation of the sculpture for

the community. Local blacksmith and sculptor Doug McLean

has worked on many projects across the Island, including

the Elissa, the Virgin Mary atop St. Mary’s church, and

multiple historic properties.

Part 3: Turning “victims”

into “Hope”

The lost 1904 statue of “Victims of the Galveston

Storm” by Pompeo Coppini has inspired a local artist

to create his own interpretation of the sculpture for

the community. Local blacksmith and sculptor Doug McLean

has worked on many projects across the Island, including

the Elissa, the Virgin Mary atop St. Mary’s church, and

multiple historic properties.

“I’m working on Colonel Bubbie’s iron work right now,

which is a big job. Galveston has the third largest collection

of contiguous cast iron-front buildings in the nation, and I’ve

done a lot of major restorations with those.”

McLean first heard about the Coppini statue in 2006

from David Canwright when they were on the Elissa crew

together. “He actually spent a lot of time searching the

warehouses at University of Texas looking for the sculpture.”

Years later when the artist was creating a commissioned

work for J. P. Bryan, Bryan showed McLean a photograph

of the statue. “The original composition was just so strong,

I was hooked. That was three and a half years ago,” Doug

says.

“I’ve been working on the project for two and a half years

off and on, between work projects and health issues. I went

to school for sculpture and have had traditional training, but

that was over 40 years ago. I fell back in love with sculpting

about six years ago.”

Working from the two existing photographs of the original

statue, his original goal was to create his own version of a bust of the woman’s head and shoulders rather than

the full figure. “When I completed that, I was so taken by

the passion in her face that I decided to finish the rest,”

he explains, adding that he was impressed by the figure’s

obvious determination.

“She’s looking at her next step, the placement of her

footstep. To me that has so much meaning because it

reflects to horror of going through anything traumatic…just

focusing on your next step.”

In his 31st Street studio McLean approaches each aspect of

the figures with care. While spending a week with his threeyear

old grandson recently, he paid special attention to the

youngster’s features so he could incorporate realistic details

like the appearance of children’s feet into his work.

“I was so frustrated by the baby’s face that I had to start

over. I couldn’t sculpt it as a dead child, which is what the

intention of the original was. I wanted to make her look peaceful,” says McLean.

“The original was a plaster study, so it’s very hard from the

photographs to tell how it would have looked translated

into bronze,” the artist muses. “Several people have asked

about the iron beam (at the figure’s feet), wondering if

there were iron beams during that time period. I’ve restored

about fifteen historic structures, and many of them had

these type of beams back to the 1870s.”

An armature pole currently supports the structure but

will not appear in the final bronze casting, and a tentative

touch of the material being used to create the nine-foot tall

sculpture reveals that it is not natural clay.

“It’s plasticine,” McLean explains, “which is oil wax clay

which doesn’t harden like clay does.” The artist used

actual cloth for the clothing on the figures, painstakingly

embedding it with the plasticine. Though the material is

not as temperamental as natural clay, McLean must roll the

large piece into his air-conditioned office at night to cool it

down and keep it from hardening too quickly.

After about 1,600 hours of work on the project, the artist is

still moved by the subject matter. “I’d be working on it and

look up at it and get very emotional,” he says. “It’s the first

full figure I’ve ever done.”

McLean expresses concern about the piece remaining in

his Island studio through the hurricane season, knowing the unpredictability of local weather. He hopes that after about 60 more hours of

work, that the statue will be able to complete its journey to becoming a bronze.

Former Mayor Jim Yarborough approached the artist, offering a permanent

location to display the work in a new city park at 823 25th Street currently under

development. The park, which is planned to open by December, will take the

place of a demolished annex building behind city hall.

It will take the support of the community to realize the vision, however. McLean

and the city estimate that $175,000 must be raised to finish the molding and

casting and complete the installation and landscaping. “It’s a challenge,” he

admits.

The casting, which will be handled by the Omega Bronze foundry in Smithville,

will take four months to achieve from start to finish. “I’m worried about moving

it,” shares McLean, “so they’re going to create the mold here on the Island, and

then do the casting in Smithville.”

Although the project is looking for major donors from foundations and large

families, any amount is welcome. It is an opportunity to personally connect with

the history of the Island and the “Hope” for a bright future.

McLean attests, “It would be a gift to Galveston from everyone who donates.”

For more information about donating to or becoming involved with the project

visit www.GalvestonSculpture.com.

The Funding Campaign for the sculpture has commenced assuring that Doug’s

clay study can be cast in bronze at a Texas foundry and be installed in Galveston

within the 120th Anniversary year of the Great Storm. A GoFundMe account has

also been set up for those who want to contribute to this important project. To

contribute visit www.gofundme.com/f/fund-galveston-hope-sculpture