In a city such as Galveston where both the written history and historical architecture exude the cultural influences of the Victorian Era, a certain portraiture of women from this time emerges - demure, obedient, perfectly coifed, and frilled from neck to wrist and ankle.

However, the efforts of the Women’s Health Protective Association (WHPA, 1900-1924) paint an entirely different picture. Although these women were undoubtedly immaculate in appearance, their modest wardrobes of floor-length day dresses belie a willingness to cohort in unseemly places and take on tasks that would make any person cautious or queasy.

From reinterring bodies after the 1900 Storm, to confronting the disastrously unsanitary conditions typical of early American cities, and working tirelessly to demand positive change from the city government, the women of the WHPA defied all the stereotypes of this era and left a legacy that permeates Galveston’s identity to this day.

Originally called the Ladies’ Health Protective Association, the first organization of this kind was started in New York in 1884. This particular assembly of neighborhood women was initially prompted by a desire to mitigate the foul odors coming from a nearby manure yard, but it grew quickly with the spread of a new concept of “public health.”

Over the next fifteen years, associations were formed in nearly every major city as well as smaller towns across the country. Some were organized to combat contagious diseases like cholera and typhoid fever, others for the purification of public water sources, but collectively, the efforts expanded to include street cleaning, garbage removal, aid for underprivileged children, the construction of playgrounds, regulations for food production and storage, and protests against factory emissions.

In Galveston, the impetus for organizing a local chapter of the WHPA presented itself amid the aftermath of the Great Storm of 1900. One major problem that confronted the city after a storm that killed a documented six thousand people (with historical estimates that place the number as high as ten thousand) was the disposal of bodies.

At least half of these bodies were trapped inside a massive pile of debris that was created by the Gulf as it invaded and scraped clean the southern half of the island, pushing all of the houses in its path into a 2-mile-long, 20-foot-high wall of wreckage.

At first, organized efforts included dismantling the wall piece by saltwater soaked piece, collecting the bodies, and placing them in makeshift morgues in buildings along the Strand for identification, but soon, this task became so overwhelming that it was abandoned. Instead, portions of the debris wall were eventually burned where they stood and became makeshift funeral pyres, since the recovered bodies were now too far gone to identify.

At first, organized efforts included dismantling the wall piece by saltwater soaked piece, collecting the bodies, and placing them in makeshift morgues in buildings along the Strand for identification, but soon, this task became so overwhelming that it was abandoned. Instead, portions of the debris wall were eventually burned where they stood and became makeshift funeral pyres, since the recovered bodies were now too far gone to identify.

To aid the city in this gruesome task, some well-intentioned individuals began to simply bury bodies wherever they were found - in front yards, alleyways, and vacant lots - but the repugnance and health risks of random graves scattered throughout the city were soon realized.

Thus, rectifying this situation became one of the first responsibilities adopted by Galveston’s newly-formed WHPA even before it was officially chartered on March 5, 1901. They fielded reports of unmarked or improper burial sites and located plots in city graveyards where the bodies could be moved.

Overseeing city laborers, the women were on site as the bodies were exhumed and then reinterred into proper gravesites. They would then post descriptions of the recovered bodies in the newspaper with the hope that some survivors would be able to identify lost loved ones.

Shockingly, it took the WHPA several years to complete this task. Makeshift graves were still being uncovered as late as 1904, and in the later years, published descriptions of the bodies were limited only to the sex of the person and the personal effects buried with them.

Illustrating the gruesomeness of this chore, the newspaper listed one case where the sex of a child whose body was recovered could not be determined, although it is unknown whether this was from premortem injury during the storm or rapid decomposition after it was buried.

Next, the WHPA turned their attention to beautification efforts inspired by the nationwide City Beautiful movement, a reform philosophy that arose in the late 19th century and focused on the aesthetics of city planning. Far more than “beauty for beauty’s sake,” City Beautiful was prompted by poor living conditions in urban areas and operated under the belief that visually enhancing these overcrowded areas would promote “harmonious social order” and increase the quality of life.

Advocates also believed that beauty naturally elicits respect from the citizenry. Simply put, people are inherently more likely to litter on a street lined with trash than they would be on a pristine sidewalk flanked by flowers and beautiful buildings.

Much of the nationwide movement was centered on architecture, but since Galveston was already overflowing with grand Victorian structures, the WHPA focused their efforts primarily on the natural elements.

This need was not only created by the encroachment of saltwater on the island during the storm that killed most of the vegetation in the city but also perpetuated by the grade-raising (1904-1911). This monumental feat of civil engineering elevated 2/3 of the city using fill dredged from the harbor but subsequently transformed that same portion into an expanse of dry, sandy silt.

First, the WHPA studied plants and trees that could exist in the island’s subtropical climate and then began replanting decimated areas that were located outside the grade-raising districts. Then as each district was completed, the association would move in and begin establishing new vegetation.

The WHPA imported oak trees, palm trees, sycamores, cottonwoods, and elms to plant on city property and sell at cost to private residences. They were also responsible for introducing the oleander to Galveston which became the city’s trademark flower.

Upon learning which species could not only endure but also thrive on the island, most notably palm trees and oleanders, the WHPA gradually stopped importing and chose instead to raise their own seeds and seedlings. By 1906, they were operating their own independent nursery on land donated by prominent islander J.C. League (founder of League City).

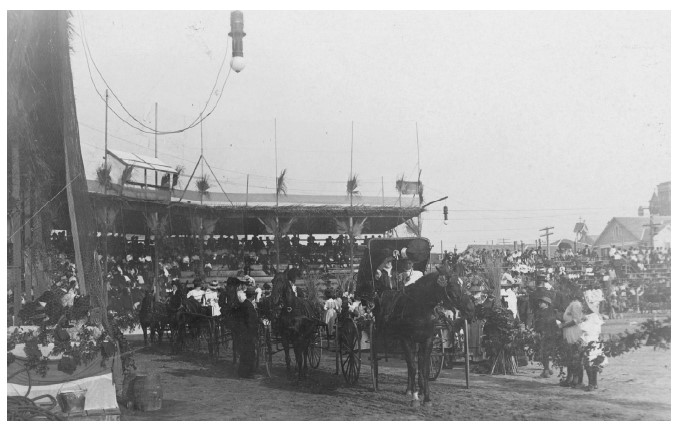

Funded by membership dues, private donations, and money made from fundraisers like seed sales and horse shows, the WHPA is estimated to have planted more than 10,000 trees and 2,500 oleanders by 1912. They also designed and executed the plans for Broadway Avenue’s elegant esplanade, plans that were painstakingly re-created by the Galveston Island Tree Conservancy after the salty surge from Hurricane Ike (2008) destroyed the WHPA’s 100-year-old masterpiece.

During the second half of its existence, before it was reorganized into the Women’s Civic League in 1924, the WHPA focused primarily on citywide sanitation and improvements for children, and they left no crevice of the city exempt or unexamined.

An early pamphlet printed by the WHPA attested that it “will become an established factor in the promotion of cleanliness, order and beauty in the city of Galveston. It stands for pure air and water, for clean streets and alleys and clean cars, for clean public buildings, for sanitary houses, for clean wharves and boats and for efficient municipal services in the collection and disposal of waste. It aims to arouse civic pride, to inspire a desire for nearness, to promote a love of order, to aid all measure which conduce to health, and to further the civic training of the young.”

An early pamphlet printed by the WHPA attested that it “will become an established factor in the promotion of cleanliness, order and beauty in the city of Galveston. It stands for pure air and water, for clean streets and alleys and clean cars, for clean public buildings, for sanitary houses, for clean wharves and boats and for efficient municipal services in the collection and disposal of waste. It aims to arouse civic pride, to inspire a desire for nearness, to promote a love of order, to aid all measure which conduce to health, and to further the civic training of the young.”

These lofty goals were almost entirely achieved and manifested themselves in ways that forever changed societal perspectives on cleanliness and sanitary conditions. Members of the WHPA exhaustively petitioned and demanded city officials implement regular street sweeping schedules for the major thoroughfares and have the alleyways cleaned regularly.

Using their own funds, they hired a sanitation expert from the medical school to inspect all food-related businesses in the city. Armed with the revolting results of this survey, they had local regulations imposed for dairy farmers, grocery stores, and bakeries.

The sanitation inspection also helped the WHPA successfully lobby the local government to pass ordinances that required property owners and tenants to assume responsibility for maintaining clean sidewalks and alleyways adjacent to their property.

The association directed the creation of dairy inspector and building inspector positions within the municipality, and they created their own watchdog groups to ensure that the new ordinances were followed. The WHPA was also responsible for the installation of the first public restrooms and the first zoning ordinance implemented in the city.

Following these drastic improvements in industrial hygiene, the WHPA became a subagent for the Red Cross, selling their anti-tuberculosis seals (labels placed on mail to raise awareness of certain issues). The first earnings from this fundraiser went to improving general civic conditions and later to employ a resident nurse. Eventually, the WHPA was able to raise enough money to build the first children’s hospital in Galveston.

They also formed a special committee focused on enhancing the everyday lives of local children. After successfully drawing attention to and improving the hygienic standards of Galveston schools, the WHPA turned to another cause - hot lunches for students. Similar to other causes sparked by the WHPA’s undertakings, this particular quest became too large for the association and was passed along to another local body.

The same happened with their efforts toward establishing recreational areas for children. After creating two parks and building a number of playgrounds, the Galveston Playground Association was formed and assumed these duties.

At its peak, the WHPA had over 400 members, but even such a large number would have affected little change were it not for the diplomatic prowess of the association’s leaders. The WHPA was subject to the scrutiny and approval of Galveston residents, yet hardly a negative word was spoken in their direction since everything they accomplished was done through private funds and local government for the betterment of their immediate neighbors.

Furthermore, several women at the helm of the WHPA at any given time were also unsurprisingly related or married to elected officials or prominent male residents. The work of these women was therefore never contained to town halls or city commissioners’ meetings but often pervaded their personal existence. Much of their influence and determination was exerted as broadly in the drawing rooms and dining rooms of their own homes as it was in public forums.

In a tribute published on December 11, 1921, the Galveston Daily News reported that the WHPA of Galveston had garnered nationwide attention during its two decades of existence, their processes and successes often sought out by other city associations as a model among the movement. “It has wielded and still wields an influence in the community hardly surpassed by any other organization, and in wielding this influence wisely and to the interest of the community, deserves credit for its work.”

That credit lies not only in their enormous and longstanding achievements, but also in their testament to the power of small, local organizations to affect real, lasting change.