One of Galveston’s

finest homes was built for a woman who died before she could ever live within

its walls. Despite its tragic beginning, the story of the residence would

become as impressive as the structure itself.

The tale of the mansion

began when David E. Bradbury (1812-1866), the captain of a windjammer, arrived

in Galveston in

1840 with his 16-year-old bride Julia Ann Livingston (1824-1858). The couple

became two of the city’s earliest settlers while Texas was still a republic and became

parents soon after their arrival.

Their first son Henry Clay

was born in 1841, followed by daughter Josephine Livingston in 1846. In 1850, a

second son Edward was born, but the child died tragically just two weeks after

his first birthday, while his mother Julia was pregnant with their fourth child

Simon Augustus.

Captain Bradbury was one

of the chief developers of the Houston Ship Channel, referred to at the time as

the Galveston Bay Channel. He borrowed money from William Hendley in 1849 to

finance his shipping and dredging operations, making several surveys between Galveston Island

and Bolivar through Trinity and San

Jacinto Bays.

After the death of his

son, Bradbury resumed his interest in Galveston’s

deep-water project that sought to deepen the island’s waterways to allow

passage for larger and thus more lucrative vessels. He appeared before the

Texas Legislature several times to acquire funds to dredge Buffalo Bayou to

enable small craft to reach Harrisburg (Houston).

On April 7, 1857, he was

given the contract for the improving navigation over Clopper’s Bar and earned

$22,725 for the project. A later contract in 1858 entailed widening the

shipping passages through Red Fish Reef and into Buffalo Bayou.

These lucrative contracts

enabled the captain to build a dream home for his family. In February 1858, he

purchased three lots at the southeast corner of Twenty-fifth Street and Avenue K and

began construction of an elegant three-story mansion.

The residence was

constructed largely from ballast materials used in Bradbury’s cotton ships,

including high quality metals, pressed red brick and other quality materials

from the east coast and Europe. As the first

brick home on the Island (pre-dating Ashton

Villa by a year, which is often thought to hold that title) and one of the

first in the state, it garnered much attention in the community.

The impressive masonry

exterior was trimmed in white woodwork and featured arched windows, seven wide

porches, and was crowned with a slate and metal roof with wrought iron

cresting. The large structure had fifteen rooms, three hallways, four

fireplaces, and the luxury of five closets.

Gas provided the lighting,

and fixtures were imported from Europe. A two-story,

brick-veneered servants quarters occupied part of the back of the property

behind the home.

Then tragedy struck the

family again on September 2, 1858, when Julia died at the age of 34. She never

had the chance to live in the stately mansion. Julia and her son Edward are

buried in Trinity Episcopal Cemetery on Broadway. It is believed that the rest

of the Bradbury family did not live in the home either, as the captain sold it

to Nelson Clements shortly after Julia’s passing.

He remained on the Island

with his children for a short time, partnering with Nahor B. Yard, former

Senator Franklin H. Merriman, Frenchman Henri de St.

Cyr, and John S. Clute, Jr. to form the Texas Telegraph Company in 1860 before

moving to Port Lavaca, where he passed away eight years later.

Nelson Clements was a

commission merchant who dealt in cotton in Galveston

and New York.

His prominent connections in society included his wife’s uncle, Louisiana

Congressman and millionaire Duncan F. Kenner. Clements was also the co-builder

of Bean’s Wharf in Galveston

in 1859 and the owner of a successful steamship company.

In December 1862, working

with Confederate General John Magruder, the businessman contracted for the

delivery of thousands of arms, munitions, and other supplies needed by the army

in exchange for cotton. Though he delivered the shipments, he spent the next

year and a half lobbying unsuccessfully for payment. His contract was

officially cancelled by the Confederacy in April 1864.

As further insult, his

grand home was used as the headquarters of Confederate Colonel Henry M. Elmore,

leader of the Twentieth Texas Infantry, and his aide Captain Dixon Hall Lewis,

Jr. (son of an Alabama

senator) during the Civil War. Colonel J. A. Robertson, prominent in Island commercial and civic life, was also stationed in

the home during that time. Perhaps partly due to the misfortune of the lost

funds from the Confederate contract or to the home’s connection to the

Confederacy, Clements soon sold the property.

Well-known banker Henry

Seeligson (1828-1887) acquired the home during the 1870s and lived there until

1883 when he sold it to Joseph Seinsheimer. Seinsheimer (1855-1938) came to the

Island from Cincinnati

in 1873 and within months was working with the firm of Marx & Kempner,

successful cotton factors and wholesale grocers.

In 1879, he married

Blanche Fellman (1860-1945), who was said to be one of the most beautiful young

women in Texas.

As the daughter of the founder of Fellman’s Dry Goods Store, she undoubtedly

brought useful business and social connections to the marriage as well. They

initially lived with Blanche’s parents, but moved the following year when their

daughter Emma (1880-1969) was born.

Seinsheimer entered into

the partnership of Freiberg, Klein & Company liquors, wine and cigar

wholesalers in 1880. The business became enough of a success to afford the

young family a large home on Market and Twelfth, as well as a live-in staff

that included their coachman Albert Gilbert, maid Jennie Lyman,

and William Washington. It was in this large home that Blanche gave birth to

their only son Joseph Fellman (1881-1951).

At only 28 years old,

Seinsheimer purchased the mansion in 1883 that would be identified with his

name from that time on. The home had fallen into disrepair and the family spent

the following months restoring it to one of the most envied properties in Galveston.

Within the first few years

he owned the home, he replaced the gas power with electricity and contracted

other updates to modernize the home. Edythe (1884-1971), the couple’s youngest

child, was the only member of the family born in the home and lived most of her

life there.

Seinsheimer’s business

pursuits were broad and incorporated a range of interests. He was part owner of

the Galveston

baseball club, and for the last two months of the season in 1890, served as the

president of the Texas Baseball League. He often commented on his

disappointment that the Island league had

failed.

Upon the death of Harris

Kempner in 1894, Seinsheimer became office manager of H. Kempner banking and

cotton and held the position until his own passing. That responsibility did not

keep the entrepreneur from following additional opportunities, and two years

later he opened the Seinsheimer Paper Company.

At the time of the 1900

Storm, the family lived at the Avenue K home with their live-in cook Dora Ware,

but no record was found to indicate whether they remained in the structure

during the incident. The first floor flooded, but the building survived with some

damage.

Afterward, Seinsheimer had

the house raised five feet, making it the first brick home to be raised in Galveston. In addition to

the necessary repair work, he added new wings to the residence and expanded the

porches to provide more entertaining space. The slate portion of the roof was

also replaced with asbestos shingles at that time.

An invitation to the

Seinsheimer home for a party was a coveted prize, as the family members were

known for being gracious and skilled hosts. Local newspaper columns mentioned

the details of guest lists and decorations much more often than they did the

accomplishments and business of Seinsheimer himself.

Festivities included

bridal showers, card-playing socials, and an annual party to celebrate the

couple’s wedding anniversary. Their 50th anniversary party was one

of the grandest Galveston

galas that year.

Seinsheimer was a charter

member of the El Mina Shrine Temple and a 33rd degree mason. He

acted as president of the Scottish Rite Temple Association of Galveston from 1906-1922. In June 1938, he

took his wife and daughters on a trip to Los

Angeles where he was scheduled to attend the annual

session of the Imperial Shrine Council.

Unfortunately, he

contracted pneumonia and died in his room there at the Biltmore Hotel. He was

82. His family brought him back to the Island

and held his funeral in their home.

Unfortunately, he

contracted pneumonia and died in his room there at the Biltmore Hotel. He was

82. His family brought him back to the Island

and held his funeral in their home.

Blanche and her daughters

remained in the house for several more years until she advertised in search of

a smaller, three-bedroom home in 1943. Shortly afterward, the Seinsheimers left

the grand residence that had sheltered members of their family for fifty years.

The trio moved to 3028

Avenue O, and Blanche passed away in October 1945 shortly after her 85th

birthday. She and her husband are interred at Galveston Memorial Park

in Hitchcock.

In April 1944, their

former home and the rear servant quarters were converted into multi-unit

apartment buildings. The floorplan subdivided the house into 25 rooms, four of

which had fireplaces.

In a much more modest

style than the previous owners enjoyed, the largest apartments offered three

rooms with a private bath. There were nine apartment units in the main home:

four on the first floor, three on the second, and two on the third. The

separate servants’ quarters were divided into two units, and a laundry room was

established in the basement. During World War II, the apartments were

designated as war housing for families of men serving at Fort Crockett.

The former servants’

quarters and garage were heavily damaged in a fire in 1946, though firemen from

three companies fought for an hour and a half to save it. In October 1960, the

Seinsheimer family unfortunately decided that the 102-year-old mansion had

outlived its usefulness and had it razed. After sitting empty for several

years, the once impressive homes’ walls tumbled down, ending its place as a

center of historical and social importance in the community.

The former servants’

quarters and garage were heavily damaged in a fire in 1946, though firemen from

three companies fought for an hour and a half to save it. In October 1960, the

Seinsheimer family unfortunately decided that the 102-year-old mansion had

outlived its usefulness and had it razed. After sitting empty for several

years, the once impressive homes’ walls tumbled down, ending its place as a

center of historical and social importance in the community.

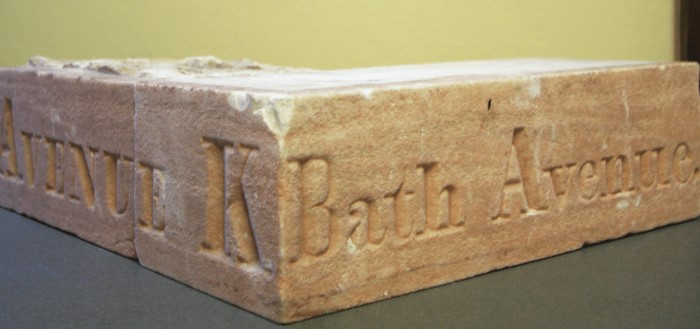

Two original street

markers - one from the side of the home facing Avenue K and the other from the side

facing Bath Avenue (now 25th Street / Rosenberg Avenue)—were

salvaged from the demolition site and donated to Rosenberg Library by R.W.

Alford who was contracted to demolish the home.

In 1978, a one-story

office building took the place of the Seinsheimer residence.

Extras:

A 1917 newspaper ad listed that the home was in need of “a

yardman, one who understands milking a cow.”

The family had an

elaborate garden on the grounds that included a much-admired peach tree.