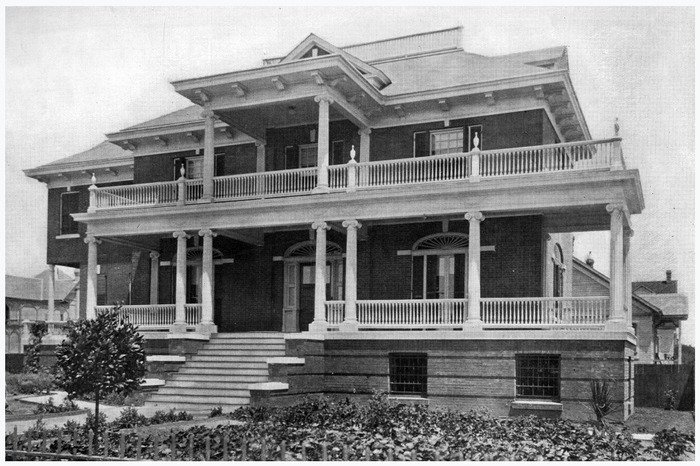

Not all of Galveston’s lost mansions were Victorian or Colonial

style homes. One in particular, the 1899 Waters Davis Jr. House, was quite

modern in appearance even though it was constructed over one hundred years ago.

The residence was built by

Waters Smith Davis Jr. (Waters Davis II, 1868-1940), whose parents, Waters S.

Davis (Waters Davis I, 1829-1914) and Sarah Allan Huckins (1838-1917), lived in

the 1898 Waters Davis House that still stands at 1124 24th Street.

Waters Davis II was an

exporter of cotton seed products as well as president and general manager of

the Seaboard Rice Milling Company. The mill and his offices were at 4002-4028

Avenue G (Winnie), approximately where Sandpiper Cove Apartments stand today.

Davis’ wife, Sarah “Daisy”

Ball League (1876-1922) descended from two of the most prominent families in

Galveston, as her name reflects. Construction on their residence began in 1899

and was completed by January 1900, three months after Waters Davis III was

born.

Prominently positioned on

the northwest corner of Broadway and 19th Street, the design

incorporated cleaner lines that were considered quite contemporary. The

Victorian era was coming to a close, and once-fashionable gingerbread style

homes were considered dated. Large enough to accommodate entertaining and befit

the Davis’ position in the community, it was not ostentatious in appearance.

Two small outbuildings at

the back of the property were the first to appear in public records and show on

an 1899 Sanborn fire insurance map, with the larger of the two being marked as

a dwelling. When the main home was constructed, this became the servants’

quarters. All three brick structures featured slate roofs.

Two small outbuildings at

the back of the property were the first to appear in public records and show on

an 1899 Sanborn fire insurance map, with the larger of the two being marked as

a dwelling. When the main home was constructed, this became the servants’

quarters. All three brick structures featured slate roofs.

The floor plan provided

the family with five bedrooms, four tiled bathrooms, two grand hallways, four

brick-front gas log fireplaces, and three wide gallery porches. The first story

featured an oak grain stairway and flooring, and the plastered walls were

covered with fine burlap and painted. The home was equipped with gas as well as

electricity and a hot air furnace.

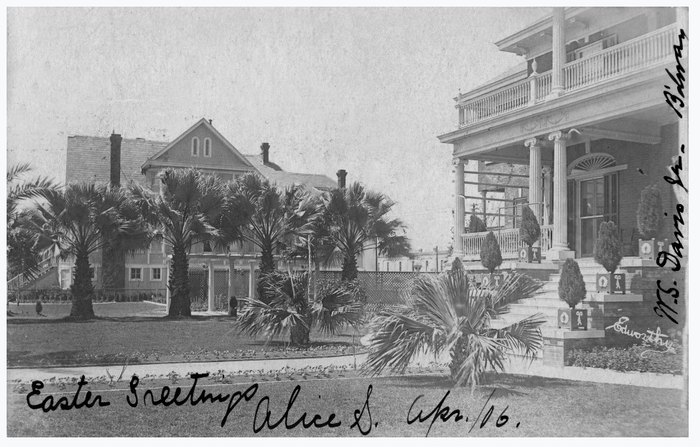

A floored attic provided

extra living space for servants, and the large basement ample storage. Gardens

on the grounds which included numerous chrysanthemums and date palms were

highlighted in local tourism materials.

The brick home’s

completion just a few months prior to the Great Storm of 1900 probably lent an

advantage against the hurricane. Because insurance papers from the time list no

repairs in the months following the storm, it can be assumed that any damage it

sustained, such as broken windows, was minimal.

Despite any difficulties

faced by the family during the months following the storm, Daisy focused her

efforts on aiding the community. She was one of sixty-six women who established

the Women’s Health Protective Association (WHPA). Among its other achievements,

the group led efforts to clean up the city as well as replace trees and plants

lost during the disaster.

The organization operated

its own nursery on land donated by Daisy’s father, John Charles League

(1850-1916), where oak and palm trees, oleanders, and a variety of shrubs were

propagated. In little over a decade, the WHPA is estimated to have planted 10,000

oaks and 2,500 oleanders across the Island.

Mrs. Waters is credited

with designing the placement of oleanders on the avenues and streets of local

cemeteries, with each location being assigned a single color—white or pink. She

even distributed free white oleander cuttings from her home, putting notices in

the local paper whenever she had them available for Galveston residents.

Normalcy began to return

to parts of the Island after the storm, and the young family enjoyed their home

to the fullest. Daisy had a large staff to assist her in managing the household

and grounds. The servants included two housemaids, a cook, handyman, nanny

(referred to as a “nurse”), yardman, and a young boy to serve at the dinner

table and perform general chores.

In 1902, Davis ran an

advertisement in the local paper in search of a gentle saddle pony for his son

and another ad soon afterward in search of a cocker spaniel puppy. A jersey cow

was bought as well to provide fresh milk for the household and kept at the back

of the property.

That was an important year

for more than the lucky child though, as his father’s company began to market

Comet Rice which is still available today. The product was delivered by horse

and buggy and bagged for shipment as far as China. The young couple began to

host numerous society gatherings of friends from Galveston and Houston,

including box parties at the Grand Opera House and dinners at the Hotel Galvez.

In February 1904, while

Daisy was pregnant with her second child, Sarah Catherine, she opened her home

to host a special sale benefitting the Altar Guild of Trinity Episcopal Church.

All sorts of fancywork pieces, candles, and other items considered suitable for

Valentine and Easter gifts were made available by the ladies of the guild, and

tea was served to attendees. The money raised was used toward the

beautification of the interior of their church.

In February 1904, while

Daisy was pregnant with her second child, Sarah Catherine, she opened her home

to host a special sale benefitting the Altar Guild of Trinity Episcopal Church.

All sorts of fancywork pieces, candles, and other items considered suitable for

Valentine and Easter gifts were made available by the ladies of the guild, and

tea was served to attendees. The money raised was used toward the

beautification of the interior of their church.

The WHPA appointed Daisy

chairman of one of their largest projects in May 1906, when over 900

Filamentosa palms were purchased in California and shipped to the Island to

line Broadway and Bath (25th Street) Avenues with the trees.

Transportation in refrigerator cars was provided free of charge by the Gulf,

Colorado and Santa Fe Railway for the undertaking.

Once the necessary palms

had been set aside for the plantings, the remainder were made available for the

public to purchase at cost. Undoubtedly, a large portion of Galveston’s palms

today were part of or descended from this immense project.

In the following years,

Daisy played a major role in many fundraising events for the Island, including

developing the plan for WHPA’s First Annual Horse Show in 1906. In between all

these activities, the family made time for trips to Europe and summers on the

east coast. Such luxuries were partially funded by the extra income of a

separate apartment building that occupied half of the property by 1912.

Waters developed a patent

for processing, sterilizing and packaging rice in 1914, bringing him acclaim

from across the nation. This allowed Comet Rice to be easily packaged for

consumers and distributed to small and large retailers.

Two years later, Daisy’s

father, real estate investor John Charles League passed away. The couple listed

their own home for sale and moved in with Daisy’s mother, Nellie Ball League

(1854-1940), at her home at 1710 Broadway. This Nicholas Clayton treasure is

still standing. William Lewis Moody III (1894-1992) purchased their residence

for use as his new residence.

The sale marked the second time a

member of the family sold their home to a Moody. William Moody III’s

grandfather, Colonel W. L. Moody (1828-1920), purchased the grand

League-Waters-Moody Residence from Sarah Ball League’s grandfather Thomas

Massie League.

In December 1920, George

Black Ketchum, manager of the Model Meat Market, and his wife Musette Newson

purchased the home from Moody for $30,000. In addition to leasing space in the

outbuildings on the property, the Ketchums were the first to create studio

apartment rentals inside the home.

Musette took advantage of

her large new home and hosted meetings of several organizations of which she

was a member, including the United Daughters of the Confederacy, Circle Number

2 of the Women’s Auxiliary to First Presbyterian Church, and the Board of the

Letitia Rosenberg Home for Women. The Galveston native was widely respected as

an organizer of the local Young Women’s Christian Association and served the

organization for the remainder of her life as a member of the board of

directors.

Musette took advantage of

her large new home and hosted meetings of several organizations of which she

was a member, including the United Daughters of the Confederacy, Circle Number

2 of the Women’s Auxiliary to First Presbyterian Church, and the Board of the

Letitia Rosenberg Home for Women. The Galveston native was widely respected as

an organizer of the local Young Women’s Christian Association and served the

organization for the remainder of her life as a member of the board of

directors.

George drove his Studebaker

away from the home for the last time on January 17, 1924, after selling it to

Danish immigrant Anders “Andrew” Enevol Berthelsen and his wife Pauline Marie

Thomsen. George, Musette, and her mother Margaret Stevenson Newson moved into

the Love Apartments at 1908 Avenue F, but the couple was divorced less than one

year later.

Berthselsen’s life was a

shining example of what hard work could bring to brave, young immigrants in the

years following the Civil War. The determined young man learned the blacksmithing

trade at the age of 14 in Denmark and immigrated to America in 1868 at the age

of 17. He found his initial success in a job shoeing horses in Illinois before

venturing out to the mining towns of Colorado. After making a successful strike

in Georgetown, he bought two farms in Iowa and returned to his homeland for his

parents, brother and sisters.

He married Pauline Marie

Thomsen (1865-1964) in 1885, and moved to Webster, Texas in 1899. In 1908, they

moved with their seven children to Cotton Gin and then to Mexia, where

Berthelsen made his second fortune with a series of oil and gas wells on his

cotton farm. Unfortunately, Berthelsen passed away in 1926 after only living in

their Galveston home for two years.

Pauline and her youngest

daughter Anna remained in the residence, splitting their time between their

island home and one in Houston. Within a year, she began taking in boarders.

Sprinkled in between the newspaper advertisements listing their apartments for

rent over the next few years, there was often a notice offering a reward for

their Boston Terrier named Tiny, who was obviously quite an escape artist.

In the late 1940s, Italian

grocer Iacopo Federighi (1891-1965) became the last owner of the home. After

much debate in the community, the property was rezoned for use as a business in

1960. Federighi took advantage of the rezoning by utilizing the Davis home as a

gas station and store downstairs, and five efficiency apartments upstairs.

A decade

later, the once elegant residence was razed, and the Broadway Service Center

was built on the lot. No signs of the home remain, but

the lasting effects of some its residents still grace Galveston Island.