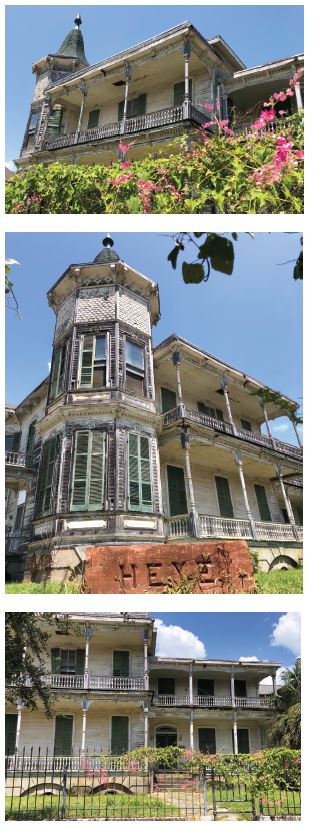

The state of disrepair of the Gustave Heye House at the corner of Thirteenth Street and Postoffice in the East End Historic District often leads passersby to believe that it has been abandoned, but that is not so. Though this unique home is obviously in need of repairs, it originally anchored a district of homes owned by German families and was a source of great pride for its original owner.

German-born Gustave Jacob Heye (1840-1915) moved to Matamoros, Mexico in 1861, where he worked for an importing firm that dealt in Texas cotton during the Civil War. In June 1869, he moved to Galveston to parlay his experience into a job with the cotton commission firm of Focke & Wilkens. It was owned by two fellow Germans he had become acquainted with in Mexico.

On Christmas Day that same year, Heye married Adelheid Focke (1849-1918), the younger sister of his boss John Focke (1836-1907). By 1872, Heye had achieved enough success to purchase lots 13 and 14 in Block 492 from Henry Frauenfeld for $1,500.

The Heye family, which now included daughter Anna Meta (1870-1922), son Paul Jacob Dietrich (1872-1893), and Gustave’s brother Jacob, remained in their home on Market Street while their new, two-story frame home was being built three blocks away on the northeast corner of Postoffice and Thirteenth Streets.

The land had originally been held by the Galveston City Company. Dr. Levi Jones (1792-1878), one of the original ten men who formed the company, purchased the land after moving to Galveston in 1838 and went into partnership with James Love, Samuel May Williams, and P. J. Menard. The associates eventually sold it to Dr. Samuel Blakely Hurlbut (1826-1862) who in turn sold it to cotton merchant Henry Frauenfeld and his wife Caroline.

Soon after the Heye family moved into the new residence, they were given reason to celebrate with the births of two more children, daughter Margarethe (1874-1904) and son Franz Johann (1875-1910).

In 1876, Heye and his brother Jacob, who had been a bookkeeper at Focke & Wilkens, left the firm and formed a wholesale grocer and cotton merchant business with Frederick Kastan under the name Gust. Heye & Co. They built a four-story brick structure on Mechanic Street as their headquarters. Heye & Co. was so successful by the end of the 1880s that the firm was able to purchase the assets of another well-known firm, Kauffman & Runge.

Jacob married the daughter of a prominent Galvestonian, Helene Jordan in 1877, and the couple moved into a home of their own on Market Street. Two years after the wedding, Jacob became seriously ill and sold his share of the business to Gustave in June 1879. Sadly, within the next two years, both he and his wife had passed away.

The addition of another son to the family, Gustav Hans (1879-1914), within weeks of Jacob’s death inspired Gustav’s decision to build a larger home. In 1880, he had their current home moved from the corner edge of the 2.5-acre lot and constructed a new residence adjoining the original.

The architect’s unusual choice to face the front of the grand home toward Thirteenth Street allowed the home’s southern-facing double veranda to look over the fashionable Postoffice Street, and provided the Heyes with a place to relax and watch passersby. The rear service wing is visible from Postoffice as well.

The appearance of two distinctive styles facing two different streets is one of the home’s unique legacies. Heye spent $18,200 for the expansion, increasing the residence to 2,610 square feet.

A two-story, polygonal corner tower at the west front corner with a candle-snuffer style metal roof was undeniably the most distinguishing feature of the home, and to this day allows the structure to be easily identified in archival photos.

The L-shaped design features a flurry of architectural Victorian details including fish scale shingle siding, hand-carved wooden rosettes above every door and window, fan brackets beneath the eaves, and dental molding. A walk-out window to a small Juliet balcony reigns over the single front door on Thirteenth, which was originally quite tall and narrow.

Seventeen rooms, including five bedrooms, four bathrooms, a formal dining room, kitchen and butler’s pantry, provided more than enough space for the family and their frequent guests. The dining room featured a stunning coffered ceiling, and there were intricately crafted wood floors throughout the home.

Seventeen rooms, including five bedrooms, four bathrooms, a formal dining room, kitchen and butler’s pantry, provided more than enough space for the family and their frequent guests. The dining room featured a stunning coffered ceiling, and there were intricately crafted wood floors throughout the home.

A front grand staircase was enjoyed by family and guests while the rear staircase was designed for use by the servants. German style, hand painted stenciling adorned most of the downstairs rooms and the bedrooms upstairs.

Five years after the completion of the reconstruction, the couple’s sixth child Otto Joseph Max (1885-1937) was born in the new home. Otto kept the family on their toes with his adventurous nature.

When he was just three years old, a local newspaper carried the story of how his family, friends, and neighbors frantically searched for the youngster who had wandered away from the yard. He was found safe at the corner of Twenty-ninth and Postoffice – quite a stroll for a little boy all by himself.

Family celebrations as well as many events for the Heye’s wide circle of German friends occurred at the home including the 1886 wedding of Gustave Opperman and Ida Louise Gustava Max Gus.

Mr. Heye entertained the T.U.V. Society Club, whose members were the younger generation of local prominent families, with a dance one evening in February 1892.

The description that appeared in the newspaper the next day stated, “at 12 o’clock an elegant supper was served in the spacious dining hall, which was most beautifully decorated for the occasion. The tables were marvels of beauty and the menu consisted of the delicacies of the season. After the supper, dancing was again resumed and indulged in until the wee small hours. The success of the entertainment was due largely to the nurturing efforts of the host, who spared no pains to afford the young folks a pleasant evening’s pastime.”

Though the family lived through several tropical storms and hurricanes in the first few years they lived in the home, nothing could prepare them for the devastation that The Great Storm of 1900 would bring.

On September 8 of that year, Heye left his office to enjoy lunch at home with his family. After their meal, he waited outside for the electric trolley to arrive to return him to work, but when it began to rain unexpectedly hard, he went back inside the house.

He telephoned his office and told them to let everyone go home for the day due to the weather. Soon the seawater was filling the streets, and the winds were so powerful that Heye ventured outside to tie the shutters to keep them closed.

Some were still torn away, and other windows broke from the force of the wind. So much rain came into the home through the broken windows that there was only one dry room in the house where his family and a few friends took shelter.

As the storm raged outside, the two-story carriage house behind the residence collapsed, killing a son’s horse. The entire roof of the east wing flew off. Rain came in like a torrent and Heye used an umbrella inside the house as he frantically surveyed the increasing damage.

In a letter he would write in the following days, he complained that the storm “ruined my beautiful parquet (floor) that runs the length of the house, and the rooms on the second floor.”

The chimney on the west side fell and broke through the roof, and Heye attempted to keep the others calm as they watched furniture, pieces of houses, and struggling people being carried by the flood waters.

In his letter he continued, “All the time I was in fear where my sons Franz and Gustave were. The latter came in the evening in sight on the corner across from us. He was in water up to his neck and almost drowned as we watched.” Luckily for the young man, a tall stranger rescued the boy and carried him to the home.

The exhausted occupants of the house slept on the wet floor of the single sheltered room since the only bed was soaked. The next morning, Franz arrived as well, having stayed at one of his father’s warehouses through the storm. At one point, he tried to come home, but the water was over his head, so he returned to the warehouse.

Heye’s warehouses were heavily damaged, and his office still held four feet of water when he arrived the next day. He immediately hired men to begin the cleaning process, sold the damaged merchandise at a discount, and listed the undamaged items for sale.

In all, Gus. Heye & Co. survived the ordeal with fewer financial losses than the majority of the island businesses. It remained in existence until his retirement in 1905.

Once repairs were made to the Heye home, life resumed its busy, happy pace with formal dinners, club meetings and special occasions. In addition to happy gatherings, the Heye home was the site of many somber events, including the funerals of young Paul Heye in 1893, daughter Margaret in 1904, Gustave Jr. in 1914, Gustave Sr. in 1915, and his wife Adelheide in 1918.

After the deaths of his parents, Otto and his wife Kathryn Alice Pauls (1893-1938) moved into the corner home and took in boarders. Kathryn continued her mother-in-law’s legacy of hosting elaborate parties in the residence including a Valentine-themed seventh birthday party in 1923 for her son, Otto Jr. that made quite an impression on the young guests.

The last Heye funerals services held in the family home were for Anna Heye’s husband Charles Krausse in 1927, Otto’s son Edward in 1936, Otto himself in 1937, and his wife Kathryn the following year.

Charles E. Esterlain was the next owner of the mansion and like many other private homes in Galveston during World War II, he and his wife took in boarders who were families of men serving in the military. In 1944, their own son was away serving as a second lieutenant in the Army Air Corps.

One of the upstairs apartments was occupied by a carpenter Ambrose Ables and his wife Hazel who worked as a checker at Evans grocery store. Hazel made extra money for the couple by mending ladies’ silk, nylon, and rayon hosiery (which were in short supply at that time) and darning men’s socks.

An advertisement listing the home for sale in December 1957 described it as being “suitable for a rooming house,” with seventeen rooms, three kitchens, and a three-car garage. When it was listed for sale again in 1963, it was described as an “apartment house.”

At that time, the home had two apartments downstairs: one with five rooms and a bath and the other with three rooms and a bath. Five individual rooms upstairs shared two common baths.

The home passed through several more ownerships, including Meredith L. and Gloria Bishop, Dr. Harry D. Brown, Ronald H. Satterly and his wife, Paul and Rosalie Turner Muehlke, and Stockton J. Greenwell. In 1984, identified as the “Towers and Galleries” home, the structure was listed for $150,000.

The original stone carriage steps emblazoned with the name Heye still sits in the corner of the front yard. Until the home is restored to its former glory, it stands guard on its corner, reminding locals of the island’s colorful past.