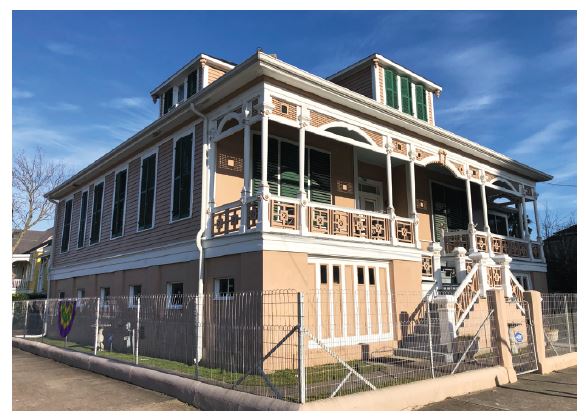

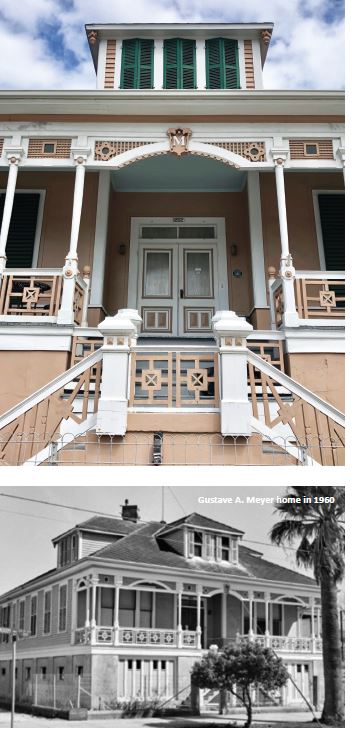

One glance at the raised cottage on the corner of Twenty-first Street and Avenue L in the Lost Bayou District reveals that there is something special about the small home. Built for Gustave A. Meyer (1839-1907) and his wife Carolina Koenig (1834-1915), both German immigrants, it was designed by the famous Galveston architect Nicholas Clayton who incorporated his signature graceful details and pleasing proportions uncommon in other small structures on the island.

Though the couple lived on the lot from the time they married in 1880, the present wood frame structure was not built until 1888 and cost $15,000 to construct. It originally faced Avenue L, but was turned to face Twenty-first Street sometime after the 1900 Storm.

Though the couple lived on the lot from the time they married in 1880, the present wood frame structure was not built until 1888 and cost $15,000 to construct. It originally faced Avenue L, but was turned to face Twenty-first Street sometime after the 1900 Storm.

The proportions of the one-story, wood-sided, and stucco home are similar to other center passage houses, but its Queen Anne ornamentation sets it apart.

A center, double-sided staircase leads to a full-width front porch and the double door entrance which features a transom window. The inset front gallery is enhanced by small boxed-X balusters, fanciful capitals, and a lattice work frieze adorned with an ‘M’ monogram for Meyer above the entryway.

A hipped roof with front and side dormers rises into a unique, diamond-shaped chimney for the central fireplace of the home. The interior fireplace mantle is also constructed of brick.

The side and rear sleeping porches are enclosed and were originally screened with a copper mesh to protect the occupants from pests.

Raised a full-story on brick piers, a basement has been built out beneath the original home to provide an extra living and storage area. A rear addition with a three-room apartment was built onto the home in the mid-1900s, but it has since been removed.

The home’s front windows are currently sheltered by non-historic metal storm shutters, which are painted green, but the dormer and side windows feature a more appropriate wooden style.

Built on a lot and a half, the residence’s rooms include a large reception hall for entertaining, two hallways, two bathrooms, three clothes closets, two cedar-lined winter storage closets, a kitchen, and a kitchen pantry.

Built on a lot and a half, the residence’s rooms include a large reception hall for entertaining, two hallways, two bathrooms, three clothes closets, two cedar-lined winter storage closets, a kitchen, and a kitchen pantry.

The structure obviously survived the blows of the 1900 Storm, but there are no records of how much damage was incurred or of any necessary repairs.

Meyer, a real estate broker, sold the home in January 1906 to Migel “Mike” Krulewich (1874-1964), a Lithuanian immigrant, and his wife Fannie Migel (1874-1956), the daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants. Krulewich worked as a jeweler at his father-in-law’s business, Migel’s Loan & Jewelry, at 2401 Market.

The Krulewiches lived there with Fannie’s widowed-mother Anna, and their four children—Ethel, Migel, Gilbert and Isabel—and the family's dark Persian cat named Lamby Face.

Though there were many prominent and successful Jewish Galvestonians at this time, there was still an undercurrent of prejudice against Jewish citizens. In December 1915, social justice advocate Rabbi Henry Cohen was made aware that the Krulewich’s son, Migel, who was a student at Ball High School, had twice undergone anti-Semitic hazing.

Though there were many prominent and successful Jewish Galvestonians at this time, there was still an undercurrent of prejudice against Jewish citizens. In December 1915, social justice advocate Rabbi Henry Cohen was made aware that the Krulewich’s son, Migel, who was a student at Ball High School, had twice undergone anti-Semitic hazing.

The Rabbi sent a letter to the principal, who had reportedly turned a blind eye to the events which re-occurred the following day. The boys’ father visited at the school to address the matter and also received verbal abuse from a group of male students. Rabbi Cohen arranged to address the entire student body at an assembly to attempt to call a halt to the behavior.

Whether or not the incidents contributed to their decision, the Krulewiches decided to send both of the sons to boarding schools on the east coast in August 1918. Migel attended the Mercersburg Academy in Mercersburg, Pennsylvania, and Gilbert went to the Peekskill Military Academy in New York.

Their mother and two sisters spent the winter in New York to be near them. This left their father alone in Galveston, with a maid to attend to house duties. All of the children would briefly return to Galveston, except Gilbert, who remained in the north.

In July 1924, the Krulewich family sold the home to the third family to reside in the house: Dr. James Antoneous Azar (1883-1955), a Lebanese immigrant, and his wife Helene Marie Bertrand (1888-1930). Azar was an eye, ear, nose, and throat specialist and a veteran of World War I.

Helene passed away six years later due to a heart infection, leaving her husband to care for young children, daughter Mary Helene, age 6 and son James, age 8.

On October 27, 1932, Azar and his then 10-year-old son were awakened at 3 a.m. by the sound of crackling flames, and the family rushed into the street in their night clothes. A fire, thought to have been caused by a leaking gas line in the attic, was fanned by high winds, and the blaze erupted into several explosion causing injuries to three of the firemen from the five fire companies that responded.

Once the flames were extinguished, the gutted home had sustained $5,000 worth of fire and water damage, which was partially covered by insurance. Azar took the three insurance companies involved to court eight months later to obtain payment.

James Jr. later served as a captain in the Air Force Medical Corps in World War II and Korea. His father continued to reside in the house until his death in November 1955.

Vincent Mazzara (1920-2005) and his wife Maria Valastro (1930-2017), Italian immigrants, purchased the home from the Azar family in 1957, after their father’s death. Vincent had spent time at the home in his youth as a friend of the younger James Azar.

Their large family filled the house with children, at least one of whom wasn’t ashamed to believe in an iconic Christmas figure.

In 1971, the local newspaper printed her letter, which read, “Dear Santa, I want a radio and a tape recorder for Christmas. Please tell Mrs. Santa Claus not to give you too many cookies and glasses of milk because I will have milk and cookies for Christmas Eve. Your friend, Giannina Mazzara, St. Mary’s Catholic School, Grade 4.”

The Gustave A. Meyer home was featured on Clayton architectural tours in the 1970s and ’80s. In addition to its outward attractiveness, it stands as a reminder of the impact that the contributions of generations of immigrant families have made in our island community.