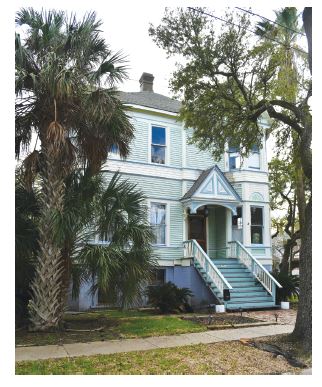

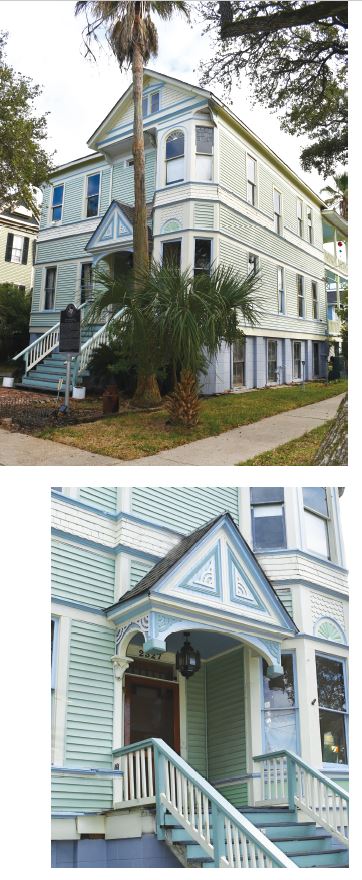

Through the years since it was built, the attractive Queen Anne house at 2327 Avenue M provided a home to several owners and numerous boarders, including three individuals who made headlines for very different reasons.

The home was built in 1894 on one and a half lots by the Hickenlooper family, on a site in close proximity to the brick warehouse of the immense Texas Cotton Press, where the majority of the stylish Silk Stocking District now exists.

The home was built in 1894 on one and a half lots by the Hickenlooper family, on a site in close proximity to the brick warehouse of the immense Texas Cotton Press, where the majority of the stylish Silk Stocking District now exists.

This area of the island was originally developed in the early 1870s to include single family dwellings, a corner store, vacant lots, and industrial sites. After the cotton press went bankrupt and was demolished, the land was subdivided and sold at an 1898 auction. That resulted in the Hickenlooper home, still quite new at the time, being surrounded by a more welcoming residential community.

The house was designed with features typical of the Queen Anne style so popular at the time, including an asymmetrical façade decorated with ornate trim. The interior stairway featured a unique gridded, partially detached spindlework pattern, still in the home, that created an open look to the tight staircase.

Two fireplaces warmed the rooms in the winter months and seven porches on both floors allowed the gulf breezes to cool interior spaces in summer.

The nine room home originally had only one bathroom, but a second was added in later years. A slate and metal roof topped the structure, and a combination of gas and electricity provided power.

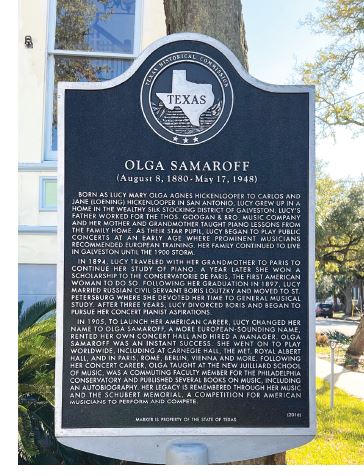

The Hickenloopers were a musical family. Jane Loening Hickenlooper (1860-1946) and her mother Lucy Palmer Loening (1841-1931) were talented pianists and music teachers. Jane’s husband Carlos (1854-1948) worked at Thomas Goggan and Brothers in Galveston, the largest and oldest music retail establishment in the state.

The couple’s eldest child, Lucy Mary Olga Agnes Hickenlooper (1880-1948) was a prodigy pianist, eventually becoming one of the most celebrated American female musicians of her time under the name of Madame Olga Samaroff.

Young Lucy had already embarked to Europe under the supervision of her grandmother to further her studies when the rest of the family, including a younger brother, survived the 1900 Storm in the home.

The Hickenloopers moved to St. Louis in 1903, and Thomas W. Stewart, owner of cotton brokerage T. W. Stewart and Company, lived there for one year before moving to a home at 1422 Broadway that no longer exists.

In 1905, the structure was raised under the ownership of James Otey, creating a basement space below that is now enclosed by concrete block walls. He too only owned the home for one year before selling it to William Alonzo James (1865-1954).

Otey was the principal and science teacher at Ball High School and, as a single gentleman, took in boarders. Among the first boarders were Joseph D. Freeman, an assistant in the manufacturing department of J. J. Schott drugstore along with his wife Ella and their son Joseph, who also worked for Schott. After Freeman died in 1907, his widow and son remained in the home.

Other boarders over the years included several other teachers, including Orville A. Tearney, a director of manual training for the Galveston city schools; James H. Garrison and Herbert F. Fulkerson, teachers at the Third District School; Wilfrid D. Stearns, principal of the Rosenberg School; and employees of Goggan, Mallory Line and other well-known island businesses.

By the 1910 census, Otey’s widowed sister Paralee Pauline Freeman had moved into the home with him along with her six children, ages 11 to 22. By today’s standards, it is difficult to imagine so many people under one roof and with only two bathrooms available.

By the 1910 census, Otey’s widowed sister Paralee Pauline Freeman had moved into the home with him along with her six children, ages 11 to 22. By today’s standards, it is difficult to imagine so many people under one roof and with only two bathrooms available.

Otey had the home updated to be fully wired for electricity in 1915.

By 1920, there were fewer residents in the home. Otey lived on the second floor with a boarder. Ulysses Homer Miles, a 27-year-old teacher at the high school, resided in the front room, and Otey retained the remainder. The first floor was rented by Harry M. Seaman, a chief law clerk with the Galveston Colorado & Santa Fe Railway, and his wife and two sons. At the time there was one bathroom on each floor.

Otey was popular among his co-workers, the students and the community, and fondly called “Mr. Chips” or “Jimmie.” That is why what occurred in 1924 came as a surprise.

In June of that year, after classes were dismissed for the summer, Otey traveled to Washington, D. C. to attend a meeting of the National Education Association. Shortly after he left, the school board summarily dismissed him from his position without providing a definite reason.

It was alluded to that he was not fit for the position though no voting member could state why, even though Otey—a member of the faculty for 19 years–had seen the school through some tumultuous periods. A letter addressed to him and signed by president of the board Charles Fowler merely stated that “it has been vaguely hinted that various and sundry criticisms have been leveled against Ball High for several years.”

In the same meeting, it was decided to release mathematics professor P. H. Underwood, due to one complaint that he was in the habit of using harsh language with his pupils. His students and co-workers denied it.

Widespread protest ensued immediately, and leading citizen Edmund Cheesborough advised Otey to stay on the east coast until the dust had settled.

Members of the student body composed a letter to the school board, stating in part, “We feel that the Galveston public schools have sustained a great loss…and that the student body generally has lost one of the best friends and educators this city has ever known.”

The Daily News was swamped with letters to the editor from citizens and Ball alumni from both on and off the island. Petitions were circulated, meetings were held, and updates often appeared in the newspaper above news of foreign wars.

Otey was kept up to date on the situation and the outcry by friends, while he attended a meeting of the Benevolent Order of Elks in Boston and visited other east coast cities.

Though the outcry happened quickly and loudly, the protestors’ victory came quietly within a month–not even noted in local news. Otey attended a rotary club meeting on July 29, a day after his return, and he received a standing ovation.

Both Otey and Underwood retained their jobs at the high school, and no specified reasons for their dismissal was ever made public.

By 1930, Otey was living in half of the home on Avenue M alone, and other half was occupied by Daisy Pothoff, an elderly woman who lived there with her son, daughter, son-in-law, and two grandchildren. She passed away in the home four years later.

After Pothoff’s death, her family moved out of the house and Otey lived alone in the home, retiring from work by 1950.

After living the majority of his life on the island, Otey returned to his hometown of Pittsburgh, Texas, shortly before he passed away in 1954, leaving his home to the First Baptist Church. The church listed the property for sale in 1955 touting ten rooms, two bathrooms, hardwood floors, and southern exposure porches.

Fred Wimhurst, Jr. purchased the home in January and sold it to Alice Henry Kerr soon after, leading to the darkest chapter in the home’s history.

Kerr had previously worked for a practical nurse named Mary Edith Tobleman who operated a convalescent home at Twenty-first and Sealy Streets beginning in 1950. Kerr was hired as a night attendant for the patients.

When Tobleman became ill and was forced to close her business, Kerr purchased the equipment in the facility. She then began operating under the name of Tobleman Nursing Home misleading clients about their association over her former employer’s objections.

The obstinate Kerr amended the name to Tobleman Kerr Nursing Home over Tobleman’s protests to being associated to the business run by a woman with virtually no experience.

Kerr herself had a tumultuous past. She had married and divorced the same man twice, with the grounds for divorce cited as the wife’s cruel treatment of the husband.

The woman opened a convalescent facility at the home on Avenue M, without obtaining a license to operate there or anywhere in Texas and remained in business for three years.

In March 1958, Mrs. Robert Wallace reported for her first day of duty at the facility. She had been hired by Kerr with the understanding that she would be familiarized with the procedures and trained to work as a night attendant.

When she arrived at the home with a friend, her insistent knocking was finally answered by one of the patients, and Wallace realized that the ten patients had been left unattended overnight though three were bed bound, and one was blind. There was no furniture in the downstairs rooms, no food in the home, and shockingly unsanitary conditions.

Wallace and her friend used their own money to purchase cleaning supplies and food for the patients, and began to tend to their needs while they waited for help from the county to arrive.

Records found by the women were the only means of identifying the patients and contacting their relatives. Those that did not need immediate hospitalization waited for family members to arrive.

Records found by the women were the only means of identifying the patients and contacting their relatives. Those that did not need immediate hospitalization waited for family members to arrive.

At the time, Kerr, who had adopted the name of Alice Tobleman Kerr, was in Nacogdoches in the process of setting up another convalescent home. Galveston authorities contacted officials there to alert them of the situation.

When she returned to Galveston several days later, she found her home empty of patients, and quickly packed her belongings to return to Nacogdoches.

The city took no action against Kerr because she had not violated any city ordinances, as few were in place at the time. The incident instigated a round of investigations of the other four nursing homes on the island, and it inspired a review of the need for additional local regulations.

The residence returned to the market, overcame its one sad chapter, and has since been home to several owners and tenants. It is currently owned by Leon Galicia and stands as a charming example of the Silk Stocking District’s beautiful architecture. In 2017 a historic marker to commemorate the residence as the one-time home of Madame Olga Samaroff was erected at the home.