Over

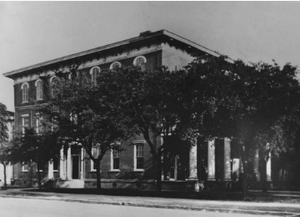

a century and a half ago, one of the finest homes on Galveston Island was built

at the southeast corner of 23rd Street and Avenue M. Referred to for

years by Galvestonians as the Waters House, the handsome, three-story structure

was owned at different times by three of the most prominent men in the Island’s

history.

The design was so unique to the area at the

time that it was alternately referred to as Colonial, Italianate, Greek Revival,

and Spanish. It was constructed of red brick imported from England and

rested on a foundation made of concrete aggregated with coral. The home’s flat

roof had wide overhangs supported by bracketed cornices and the rear of the

home provided second- and third-story galleries. The sills to every outside

door were made of marble.

The design was so unique to the area at the

time that it was alternately referred to as Colonial, Italianate, Greek Revival,

and Spanish. It was constructed of red brick imported from England and

rested on a foundation made of concrete aggregated with coral. The home’s flat

roof had wide overhangs supported by bracketed cornices and the rear of the

home provided second- and third-story galleries. The sills to every outside

door were made of marble.

Green blinds hung beside the tall slender

windows that looked out on spacious gardens filled with poppies, hollyhocks,

and cannas of canary yellow and red. The deep lot was also filled with a

variety of trees and shrubs, surrounded by a white picket fence.

The palatial residence boasted 30 rooms, some

of which were described as large enough to contain a modest bungalow. The

kitchen, designed to accommodate room for serving large numbers of guests, had

its own over-sized fireplace and oven.

Much of the surrounding land was covered by

the arms of Hitchcock’s Bayou at the time (since filled in), an area popular

with recreational fishermen. This direct

access to water was likely the reason that the land on which Waters House was

built had an unusual history prior to the home’s construction.

In 1857, the United States

government imported camels to be tested for use by government service in the

arid regions of west Texas.

When the animals arrived through the port

of Galveston from Alexandria, Egypt,

they were held in pens on the parcels of land near the bayou to await their

removal to the interior of the state.

Understandably, the odd creatures drew curious visitors. Adventure-seeking

boys had great fun sneaking in to attempt to ride them, until the camels would

revolt with a quick bite. This curious chapter was short lived, and the lots

were destined for grander sights.

LEAGUE

Thomas Massie League (1808-1865) was one of

the first settlers of Houston,

as well as its first postmaster and a member of the original Chamber of

Commerce. He was also a successful merchant and part owner of League, Andres

& Company, a general store in Houston

that he established with John Day Andrews (the city mayor) in 1838.

He moved to Galveston in 1846 with his wife Esther

“Hettie” Yarral Wilson (1812-1884) and their children. The eldest of those

offspring, Thomas Jefferson League and Esther Ann League, were born in Baltimore. Tragically,

the couple lost four of their next five children, all born in Texas.

When John Charles League was born in 1850,

the couple decided to return to League’s home state of Maryland to educate their two older children

and to provide John with what they hoped would be a healthier climate for a

newborn. After four years in the North, the family returned to the Island.

On the 1860 census League’s listed occupation

was “Gentleman.” His extended family household included his wife and youngest

son Charles, his son Jefferson and wife Mary (the daughter of Samuel May

Williams), and his daughter Esther along with her husband Clinton Wells and

their growing family. The size of his household, as well as a position in the

community that involved entertaining important men from across the state,

undoubtedly contributed to League’s inspiration to build the grand home that

was a source of pride for the entire community.

League was one of the deed holders of the Hendley Building

on the Strand and the owner of his own wharf,

and he had numerous real estate dealings. He was also a close friend of

Reverend Benjamin Eaton of Trinity Episcopal Church, where he served as a

vestryman. Just two months prior to his death in 1865, he received a

presidential pardon for his contributions to the Confederacy during the Civil

War.

League’s heirs sold the home to Colonel

Jonathan Dawson Waters (1808-1871), who had previously owned a large sugar and

cotton plantation on the Brazos named Arcola.

The land in Fort Bend County

where he made his fortune is now a residential development called Sienna

Plantation.

WATERS

Waters, although a successful businessman

like the home’s former owner, had a much darker reputation. Before the Civil

War, he was known to cruelly overwork the slaves on his plantation and even

shot a neighbor in cold blood over a business disagreement. He was never tried

for the murder-reflection of his power in the Fort Bend

community.

Waters was married three times. Only three

months after his first wife Sarah Elizabeth Grigsby died in 1848, he married

Clara Byne, the 21-year-old daughter of a neighbor. She was reportedly the love

of his life, although twenty years younger, and when she passed away after a

long illness in May 1860, he buried her in a pecan orchard behind their plantation

home. He later married Clara’s sister, Martha Byne McGowen, and adopted her

three children.

Waters’ changed League’s former Galveston residence into

a fashionable hotel known as Waters House, reserving a portion of the mansion

for use by his own family. It soon grew to have the reputation of offering

elegant accommodations for traveling businessmen from across the South. An

August 1866 advertisement described it as follows:

“The location of this house is in full view

of the Gulf, gives its guests the full benefit of the pure, cool breezes, while

an omnibus is always in attendance, ready to carry them to any portion of the

city, free of charge. Capt. Byne, the polite clerk, makes the comforts of the

guests his special study, while Mr. Smith, the steward, is indefatigable in

procuring everything the market affords and seeing that it is served up in the

best style.”

The Captain referred to was Joseph Henry

Byne, Water’s brother-in-law. Waters’ wife Martha was listed as the

proprietress and oversaw the housekeeping and hiring all staff for the hotel.

Waters House was also a fashionable venue for parties and gatherings. The

Independent Club, La Favorite Club, German Club, and other organizations held

their meetings, dances, and other special events in the generously sized

first-floor rooms. Cricket games and gardens parties were held on the grounds

surrounding the home.

Despite its popularity, the success of the

venture was inconsistent. Years such as 1867, when Galveston was visited by a Yellow Fever

epidemic as well as a hurricane, were difficult. Waters’ health declined, and

he died in 1871 after losing most of his fortune to the crash in sugar prices

after the Civil War.

He left the bulk of his estate including

Waters House to his wife Martha who in turn made a gift of the deed to her

daughter Clara Vardell. Unfortunately, due to a successful lawsuit against the

estate by Waters’ creditors, the property was sold for $15,370 in gold to pay

her father’s debts in 1873.

E. K. Nichols purchased the residence but

only owned it for a mere two years before he listed the partially furnished

home for sale in early September 1875. His timing could not have been worse as

less than one week later, a severe storm ripped the entire roof from the home.

Flying about 120 feet from the property, it

nearly killed two men. Over 100 other homes in the area were wrecked or badly

damaged. Within

two months, the roof was replaced, all repairs were made, and sale of the

mansion was being advertised through H. M. Trueheart’s real estate office.

Proprietress Madam A. Bourcier announced the

re-opening of Waters House in March 1876 and oversaw the operations for two

years before the property was again listed for sale.

MOODY

Entrepreneur Colonel William Lewis Moody, Sr.

(1828-1920), the founder of the Moody business empire in Galveston, purchased it in 1878. Once again

serving as a grand private residence, Moody and his wife Pherabe (1839-1933)

embellished the home with improvements including crystal chandeliers, large

pier mirrors, and fine woodwork. They also enlarged some of the rooms, taking

the room count from 30 to 21. During this era, the section of Hitchcock’s Bayou

that wound through the area was filled, hence its current name-the Lost Bayou

District.

Entrepreneur Colonel William Lewis Moody, Sr.

(1828-1920), the founder of the Moody business empire in Galveston, purchased it in 1878. Once again

serving as a grand private residence, Moody and his wife Pherabe (1839-1933)

embellished the home with improvements including crystal chandeliers, large

pier mirrors, and fine woodwork. They also enlarged some of the rooms, taking

the room count from 30 to 21. During this era, the section of Hitchcock’s Bayou

that wound through the area was filled, hence its current name-the Lost Bayou

District.

The house and its grounds, considered among

the handsomest in the state, returned to their former glory as the center of

the most elite Galveston

social events. Newspaper accounts regaled it as the tasteful site of numerous

festivities, card parties, dances, and even funeral services for family members

and friends. A photograph of the Moody residence appeared in a 1903 booklet

titled “Texas: Imperial

State of America”

that was printed by the Texas World’s Fair

Commission to promote the finest things Texas

had to offer.

The colonel and his wife were in New York when the 1900 Storm struck, and it was Moody

company policy that he and his son Will Junior could not be off the Island at the same time. The younger Moody rode out the

hurricane with his wife and daughter in his father’s solid, imposing mansion,

though his own house was located on the same block directly behind it. When the

grade-raising took place, the colonel had his house raised three feet, using

about 350 jack screws placed under the building.

Moody’s widow remained in the home for two

years after her husband’s death in 1920, but eventually moved into the

Buccaneer Hotel.

CHURCH

YEARS

Galveston’s

Central Christian Church purchased the three-story home in May 1922. After

raising $50,000 from its membership, the congregation made a successful appeal

to the community for the remaining $25,000 necessary to complete the purchase.

A partition of the lower story of the

building was removed to make a temporary auditorium space for services, while

plans for a larger auditorium on the grounds were considered. The home, still

described as “spacious and splendidly preserved” provided ample room for

services, a bible school, and social activities.

The home’s ties to the Island’s religious

community continued with its next chapter when it was sold for $65,000 to the

local Roman Catholic Diocese in 1927 for use as Kirwin High School.

The sale included the main residence, stables, and thirteen and a half lots.

The pastor at the time assured the community that no immediate alterations to

the property were planned. That fall approximately 60-75 male students began

classes at the mansion. The former stables were used as the athletic dressing

room.

The home’s ties to the Island’s religious

community continued with its next chapter when it was sold for $65,000 to the

local Roman Catholic Diocese in 1927 for use as Kirwin High School.

The sale included the main residence, stables, and thirteen and a half lots.

The pastor at the time assured the community that no immediate alterations to

the property were planned. That fall approximately 60-75 male students began

classes at the mansion. The former stables were used as the athletic dressing

room.

END

OF AN ERA

Colonel Moody’s residence was torn down in

1942 to make way for a new $100,000 school building. Originally retaining the

name Kirwin, the school currently occupying the lots of the former mansion is

called O’Connell High School.

During the demolition, the

original imported English bricks of the house were salvaged and donated by the

directors of Mary Moody Northen, Inc. to the Galveston Historical Foundation to

be used to strengthen a crumbling wall of Ashton Villa’s Carriage House at 24th

and Broadway. The bricks were nearly a perfect match. Those bricks and the

memories of the high school students who attended classes there are all that

remain of the once grand mansion.