Out

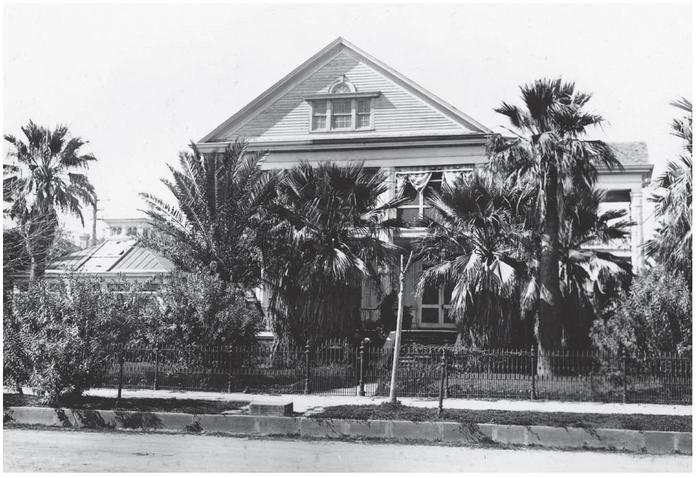

of all the lost mansions in Galveston,

the colonial style home that once stood proudly at Twenty-fourth Street and Broadway may

have had the most varied history on the island, evolving from the small cottage

of a slave trader to the beautiful home of wealthy philanthropists, and

eventually a gift to the community.

The lots of land where the home once stood

were first sold by the Galveston City Company to Isadore Dyer (1813-1888) in

1844. He sold them to S. Jacobs the following year, who in turn sold them to

Henry Alfred Cobb (1817-1892) in 1846.

Cobb

Cobb hired contractor William Shields to

erect a home for him on the property in 1846, which was considered at the time

to be the outskirts of Galveston.

Due to the expense of transporting lumber to the Island,

the structure was only a modest cottage of three rooms, facing Twenty-fourth Street.

The block of property was also bound by Avenue K, Bath Avenue (25th Street), and Broadway.

At the time, Broadway was trying to live down

its former name of Prairie Avenue,

a short road that was kept clear of weeds by each householder’s slaves using

long-handled scythes.

A native of England,

Cobb moved to Texas

in 1837 and engaged in the dry goods business until 1839 when he left to enlist

as a cavalry volunteer for a year to defend the Republic against Comanche

attacks. Cobb then served in the Texas Navy where he was eventually promoted to

Sailing Master.

After his resignation from service, the

merchant married in Galveston

in 1840 and engaged in exporting large quantities of cotton and importing

general merchandise. He served as vice consul of France for a short period, and was

one of the earliest members of the fire department.

A slave owner in the 1840s, Cobb and his

brother purchased a vessel named the Rover for the purpose of

transporting and selling slaves in New

Orleans. They utilized their British citizenship to

circumvent restrictions on these acts, including the numbers of slaves allowed

on board and offered for auction at one time.

For reasons unknown, Cobb sold the property

in 1846 not long after he built the three room house. He eventually left for San Francisco, where he

made his fortune in real estate and spent the rest of his life using his wealth

and position to fight against the rights of African Americans.

The small house and land changed hands three more

times in 1846 after Cobb bought it, purchased by M. L. Burnham, S. R. Lewis,

and finally by Joseph Osterman (1798-1861). It

wasn't that uncommon then for land to be purchased and then resold within days

or weeks of each other without the house actually being occupied.

Osterman

Osterman, a Baltimore silversmith, married Rosanna Dyer

(1809-1866) in 1825. When he suffered financial misfortune in 1839, Rosanna’s

brother, Major Leon Dyer, financed the couples’ move to Galveston.

Osterman brought along a stock of merchandise

with which he opened a new business in a wooden structure across from City National

Bank. The couple lived in an apartment on the second floor above the shop.

His keen sense of business and reputation for

offering the latest products quickly brought him success and fortune. He is

credited with being the first to bring items such as matches, stoves, and

cooking ranges to the Island.

The purchase and move to the three-room

cottage greatly improved he and his wife’s living situation, and subsequently,

his good fortune was reflected in his new home. (Another brother of his wife Rosanna,

Isadore Dyer, had originally first purchased the property in 1844 from the

Galveston City Company but sold it in 1845.)

Soon after purchasing the house he

immediately raised it on brick piers, adding a reception room on the south

side. Not having any children of their own, the couple invited Rosanna’s

younger sister Hannah to move from Baltimore

to live with them.

Osterman also erected a two-story structure

larger than his own home on the Bath

Avenue side of the property. The first story

served as a stable for horses, a cow, and several burros which were used as

pack animals for delivering goods. The second story housed eight slaves. In the

late 1840s, the first above-ground, round cypress cistern was built on the

Osterman property.

During that era, large blocks of ice were

brought to Galveston from Maine in schooners each winter, but they

melted away long before the summer months ended due to the tropical climate.

The Osterman home was the first in Galveston

to have it's own icehouse, constructed with double walls of heavy planks. The

spaces between the planks were filled with crushed charcoal for insulation.

Much admired, it was soon copied by other families on the Island

who could afford to do so.

During that era, large blocks of ice were

brought to Galveston from Maine in schooners each winter, but they

melted away long before the summer months ended due to the tropical climate.

The Osterman home was the first in Galveston

to have it's own icehouse, constructed with double walls of heavy planks. The

spaces between the planks were filled with crushed charcoal for insulation.

Much admired, it was soon copied by other families on the Island

who could afford to do so.

Guests were often entertained at the home, and

the Ostermans became renowned for their hospitality. Among those who enjoyed

their cordiality were David G. Burnet, Sam Houston, Mirabeau B. Lamar, Dr.

Anson Jones and Gail Borden. The streets of Galveston were ankle-deep in sand, and even

the grandest of citizens and celebrities often reached the doorstep in bare

feet, with the with their shoes and silken hose in their hands.

Isabella Dyer (1836-1902), the daughter of

Rosanna’s brother Joseph, also came to live with them in 1846 along Rosanna’s

younger sister Hannah. That same year, Moritz Kopperl (1826-1883) became an

employee of Osterman, and boarded with the family as well.

In 1852, a second story was added to the home

along with a colonial front porch gallery, supported by large columns. With no

homes on lots to the south, the second story porch offered an unobstructed view

of the rolling Gulf and the sand dunes along the beach.

The Ostermans property also had a hot house,

vegetable garden, and a beautiful arbor with trailing native and exotic vines.

A fence surrounded the home to protect the gardens and property from hogs,

goats and donkeys that ran loose on the Island.

A devastating yellow fever epidemic broke out

in Galveston in

1853. Rosanna, an experienced nurse, erected a tent on her lawn and cared for

anyone who required medical attention. One-sixth of the town’s population died

during the outbreak including three of Rosanna’s relatives, two of whom were

visiting from out of town and a four-year old boy.

Joseph Osterman met a tragic fate in 1862

when he was accidently shot and mortally wounded by a workman in a gunsmith

shop. Now running the property alone, Rosanna once again opened her home and

property during the Civil War to treat disabled and wounded Confederate

soldiers.

The carpets of the home were cut and

fashioned into slippers, and sheets were torn for bandages and wadding for

dressing wounds. Because there was no kindling to be found on the Island during the war, the large old stables were chopped

into firewood to use to warm the soldiers. The slaves who had lived in the

upper floor of the stables had already dispersed.

Rosanna was killed on February 2, 1866, in

the explosion of the steamship W. R. Carter on the Mississippi River, and

buried in New Orleans.

She left an estate valued at over $204,000, much of which she bequeathed to

charitable organizations. She left the income from the Osterman

Building at Twenty-second and the

Strand in Galveston

to her nieces Isabella Dyer and Hannah Dyer Symonds and to her friend Mary Ann

Brown.

Kopperl

The following June, after knowing each other

for twenty years, Moritz Kopperl and Isabella Dyer married and purchased the

Osterman home for their own. They also bought a half-block of property to the

north.

The following June, after knowing each other

for twenty years, Moritz Kopperl and Isabella Dyer married and purchased the

Osterman home for their own. They also bought a half-block of property to the

north.

Kopperl had become president of the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe

Railroad, president of the Galveston National Bank, and served two terms in the

state legislature. At one point, he was the largest importer of coffee in Galveston. As a result of

his ties to the railroad, the town of Kopperl, Texas was named in his

honor.

Other than building a replacement for the

stable that was lost during the war, the Kopperls made no changes to the

property for many years. In 1877 when the original wooden cistern and

replacement stable burned, a third stable was built on the property.

Kopperl died somewhat unexpectedly in 1883 on

a trip to his homeland of Bavaria

with his son. After his death, his wife Isabella became well-known for her

philanthropic work including serving as the first director of the Israelitish

Orphans Home. She spearheaded efforts to replant the Island after the post-1900

Storm grade-raising and is said to have brought the first palms to Galveston.

The eldest of the couple’s sons, Herman,

married in 1889 and erected a separate home on the Kopperl lots nearest Bath Avenue. Their

younger son Moritz Jr., a successful lawyer, lived in the original home with

his mother. When he married in 1898, his new wife joined them.

While at a convention in California with several

other ladies in 1902, Isabella was killed in a runaway horse carriage accident.

The companions from Galveston

were injured but survived.

After Moritz Jr. died in an accidental

drowning incident in 1917, his wife moved to New York to be near their sons who were in

school there. The large house sat empty except for caretaking staff for years

until 1921, when Brewer W. Key, president of the Gulf Lumber Company, purchased

the home and four and one half lots for $17,000.

YWCA

Hiring architects Stowe & Stowe and

contractors Coyle & Coyle, he then spent more than $50,000 to double its

size and remodel it into an attractive three-story residence of 43 rooms, which

he presented to the Young Women’s Christian Association as a memorial to his

wife, Julia Vedder Key. Julia, who passed away in September 1919, had been a

life member of the association and an active volunteer.

Brewer intended for the home to provide

affordable housing to young employed women, as well as an activities

headquarters for the Y.W.C.A. With accommodations for approximately 100 girls,

the impressive home offered new opportunities to the organization. By the time

the Julia Vedder Key Memorial YWCA Home formally opened to the community with

an open house on Dec. 29, 1921, the room reservation list was almost entirely

filled.

The porte cochere with concrete steps and

balustrades faced Broadway, across the esplanade from Ashton Villa, and its

second story balcony provided an exceptional view of the grand homes on the

thoroughfare. An entrance from Twenty-fourth

Street led directly into a spacious first floor

reception hall. Attractive French doors separated this room from the parlor and

living rooms, both of which featured pressed brick fireplaces with marble

mantles.

The porte cochere with concrete steps and

balustrades faced Broadway, across the esplanade from Ashton Villa, and its

second story balcony provided an exceptional view of the grand homes on the

thoroughfare. An entrance from Twenty-fourth

Street led directly into a spacious first floor

reception hall. Attractive French doors separated this room from the parlor and

living rooms, both of which featured pressed brick fireplaces with marble

mantles.

A corridor and another set of French doors

led from the parlor to a dining room that featured windows on three sides with

an art glass window on the west wall. An oversized china closet with glass

doors was stocked with enough service ware to provide for large gatherings.

Modern labor-saving devices including an

electric toaster filled the kitchen, and the pantry cupboards were fronted with

sliding glass doors. Adjoining the kitchen were two large storerooms, and a

walk-in refrigerated room equipped with an icebox, sink and drain board.

A secretary’s residential room was located on

the southeast corner of the south wing, with its own private bath. Eleven

dormitory rooms were also on the ground floor, each with two closets designed

with shelves, clothes poles, and private lockers.

White tiled communal bathrooms measuring 20

by 24 feet were on both the first and second floors. Each included two

bathtubs, six sinks, three showers, and four toilets, all with nickel-plated

trimmings. A two-story garage included a laundry facility and storeroom.

The dormitory rooms on the second floor

duplicated those below except that the polished hardwood floors were finished

with deafening quilts, to buffer sound between stories. The white enameled

woodwork of the walls was trimmed with mahogany. Screened sleeping porches

extended across the front and south sides of the second story to use during the

warmest months.

In preparation for any resident who might

become ill with an infectious disease, a hospital room on the second floor was

equipped with everything necessary to treat the infirm, including a private

bathroom.

Two large stairways led to a third floor that

extended the entire length of the building, and over the three wings. Arranged

as a recreation room for the girls, the open area could be used as a dance hall

or space to play games. A stage occupied one end of the room for performances

and presentations. Hidden storage areas were designed beneath the windows to

store equipment.

The gracious, Southern style home provided a

setting for thousands of girls and young women to enjoy slumber parties,

showers, teas, parties, and banquets. Weddings held at the home included one

for Mrs. Key’s niece Vera Ellis’ marriage to A. B. Crow.

Members of the Y.W.C.A. could take part in

the Young Employed Women’s Group, Young Matron’s Club for married women, teen

activities and special events. Classes in French, Spanish, swimming, ballroom

and modern dance, furniture refinishing, and art were also offered. A “mothers’

day out” type of program called “Holiday from Apron Strings” invited ladies to

escape from housework each Wednesday from 10am to 4pm to enjoy swimming,

exercise, cards, ping pong, badminton, and volleyball.

After 27 years as home to the Y.W.C.A., the

home required cost prohibitive repairs and updates, and it changed hands for

the last time. Broadway Medical and Dental

Building, Incorporated

purchased the Julia Key Memorial Home for $52,000 in March 1948 and had it

demolished. It was replaced with a large three-story structure designed by Galveston architect,

Andrew Fraser.

The grand home that grew from a three-room

cottage now only exists in photographs.

Sailing back to Galveston from a business trip to Jamaica in 1841, Osterman brought the first

oleanders to Galveston

as gifts for his wife Rosanna and sister-in-law Amelia (Mrs. Isadore) Dyer. The

double-pink variety was named after Rosanna and cuttings soon bloomed

throughout what would eventually become known as the Oleander City.

The original planting can still be enjoyed at the site of Amelia’s former home,

beside a Texas State Historic Marker at 902 Twenty-fifth Street.