The tears that involuntarily erupt as his mentee speaks of his incredible artwork, an emotion so powerful that it overtakes his son, and the kind and reverent words of his former wife—these are not the complete sum of what local artist and icon Jack Morris left behind when he succumbed to COPD last year, but they do paint a picture that perhaps not even Jack could have captured.

It is a portrait of a man who will forever be cherished by those who love him, not only for his staggering talent, unapologetic opinions, and a wisdom only bestowed upon those who dare to build their life from nothing, but also for an unbridled dedication to his community and a legacy that will forever linger within the hallowed halls of Galveston history.

“Not many people know this, but my dad’s first job was picking cotton in Bryan, Texas,” says Charlie Morris. While recounting the biographical highlights of his father’s career, Charlie’s voice hints at an obvious pride in his father and his accomplishments and for the fact that Jack Morris was, as Charlie describes, “self-made.”

Born on June 13, 1941, Jack Morris was aware of his talent and love for art at an early age. “Art drove him. He said if he couldn’t paint, he couldn’t breathe,” says his former wife, Christina Rathbun. “He was actually accepted to the Art Institute of Chicago.” But Jack did not think it was wise at that time to pursue a career in art, and so he chose architecture as a suitable alternative.

Jack left the cotton fields for Texas A&M University’s College of Architecture in the late 1950s and passed the exam to get his architecture license well ahead of his classmates, even before his schooling was complete. He then enlisted in the U.S. Army where he served as an artillery scout stationed in Kansas City. From there, he took a job in Huntsville for the prison system and oversaw their architectural department.

“All of his employees—draftsmen, etc. were prisoners. I really think that’s why his outlook was, ‘always give people a chance.’ He was picking cotton for his first job. He was very open to diversity and just working for what he had,” says Charlie.

Jack then took a job with Reed & Clements of Texas City, where his big assignment was also the first of innumerable impressions that he would leave on Galveston Island. “Jack was part of the team who built College of the Mainland (COM). He was one of the designers,” explains Christina.

“And there were certain things—like the theatre. It’s a very interesting theatre that the [college] has and Jack designed that.”

This was also the job that introduced him to Louis Oliver, a renown Galveston architect who designed and oversaw countless projects for the city, county, and state as well as churches and residents. Jack eventually left Texas City to join Oliver’s firm and make his home in Galveston.

Christina met Jack in 1974 when she came to Galveston from Sweden as a Rotary Fellow. “The Galveston Rotary Club sponsored me, and at that time, Jack was an architect with Louis Oliver,” says Christina.

Christina met Jack in 1974 when she came to Galveston from Sweden as a Rotary Fellow. “The Galveston Rotary Club sponsored me, and at that time, Jack was an architect with Louis Oliver,” says Christina.

With Oliver, Jack designed and remodeled a multitude of buildings both on the island and the mainland. “He did doctor clinics, he did several banks, and he did a lot of homes on the west end. He was also the lead architect on the housing development Isla del Sol. That was Jack’s project. He designed all of those houses,” Christina explains.

Then in the 1980s when George Mitchell began to renovate the Strand, Jack forged a relationship with the oil tycoon and was responsible for executing a large part of Mitchell’s vision.

“Jack was very instrumental in the remodeling of the Strand buildings, because remember they were all like warehouses [at that time],” Christina says of the desolate, unkempt Strand of the 60s and 70s. Under Mitchell’s direction, Jack played a crucial role in elevating the Strand to what was then more akin to an outdoor shopping mall than the tourist destination it is today.

She continues, “Back in those days, we’re talking early 80s, the Strand was very upscale. We didn’t have all of those gift shops on the Strand. Jack did the Eisenberg jewelry store, really upscale, and he did a lot of restaurants. He actually had his architectural office inside Old Galveston Square at one time, and he developed all the buildings on [the north side of the Strand] between 21st and 22nd Streets.”

By the mid-80s, Charlie says, Jack had a thriving architecture practice of his own. “But then he got burned out with that and that’s when he went over to the art side. My dad had always been an artist—I have pieces he did back in the 50s and 60s.”

Jack opened his first gallery in the Trolley Station building on the Strand where Hubcap Grill is currently located. Here, he made what is undoubtedly his biggest contribution to the Galveston arts scene aside from his prolific body of work.

“Back in the late 80s, there was a high-end restaurant next door to the gallery,” Charlie remembers. “I think it was called Zan’s, and my dad would stay open late on Saturdays so people would come over during their meal or after their meal, and he started realizing that it was beneficial.”

“Back in the late 80s, there was a high-end restaurant next door to the gallery,” Charlie remembers. “I think it was called Zan’s, and my dad would stay open late on Saturdays so people would come over during their meal or after their meal, and he started realizing that it was beneficial.”

“Then I believe a couple other galleries started doing the same thing,” he continues. “And as far as I know it, that is how ArtWalk got started. Obviously, Galveston Arts Center is—on paper—what’s known as how ArtWalk started since they’ve been there from the get-go, but even before that, it was basically my dad and a couple of other galleries. So, it was a grass roots deal.”

Over the next several years, Jack moved his galleries into whatever Mitchell building had most recently been renovated, helping to draw attention and customers to the newest Strand hotspot. “Then when the building would get popular,” Charlie explains, “they would move him to another building.”

After relocating at least three times, Jack finally landed at the space on Postoffice Street now occupied by Fullen Jewelry and opened a gallery called Atelier Ӧ, “Fine Art for Discriminating Collectors.”

After relocating at least three times, Jack finally landed at the space on Postoffice Street now occupied by Fullen Jewelry and opened a gallery called Atelier Ӧ, “Fine Art for Discriminating Collectors.”

“Before that, it was always Third Coast Gallery. Then when he moved into that location, he started up the new name,” Charlie says. The gallery operated until 2002 when Jack left Galveston to take a position as an observer/researcher for a non-profit fishery.

Upon returning to Texas, he oversaw the estimating department for a tile and flooring company in Houston while simultaneously contributing to architectural projects in Austin, Colorado, and D.C.

“Then it was in 2013, when the two of us went in together and decided that we wanted to come back and have a gallery again, that we took the name Third Coast Gallery back,” Charlie explains. Around this time, Jack made the acquaintance of a future island transplant, Betsy Campbell.

“I met Jack on my second visit to Galveston,” Betsy remembers. Betsy’s cousin and her husband operated a gallery on the corner of 25th and Mechanic, a couple of doors down from the recently revived Third Coast.

Their connection was not immediately forged, Betsy admits, but a few years later, she ran into him at Press Box, one of his regular haunts. “He loved their chili,” she laughs.

“We got to talking, and we just hit it off. And at the time, I was trying to decide whether or not to move here, and he is one of the reasons that I did.”

She first opened Betsy by Design, a boutique stationer and printer, inside a shared commercial space at 25th and Market, but in early 2017 ended up in the exact space her cousin had occupied years prior, just down the block from Jack. It was all her own, but less than six months later, she was flooded by Hurricane Harvey.

“Jack reached out and asked, ‘Hey, how are you doing?’ I said, ‘I flooded, Jack.’ He said, ‘Hang on, I’m going to call you back,” Betsy remembers.

When he called back, he extended Betsy an invitation to move her shop into his space, and she has been there ever since. During the time she worked alongside him prior to his passing, Betsy developed a sincere affection for the seasoned Galveston artist and his remarkable work.

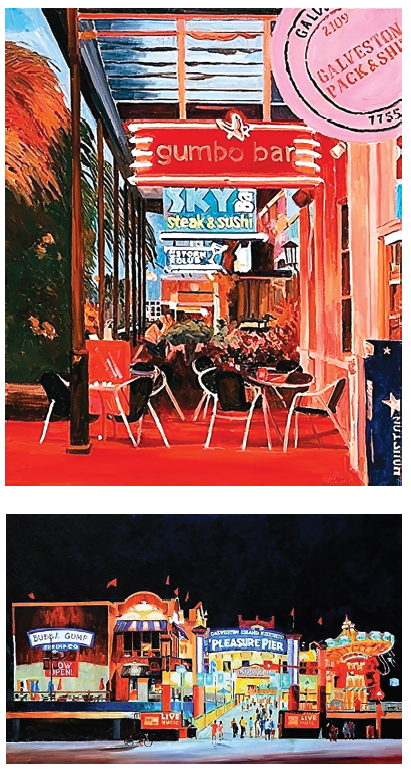

“His work was the strongest in the pieces that evoke the feeling—like you are there, in that moment, on that street,” she says.

One of her favorites is called, “Tremont After the Rain.” When the man who commissioned it passed away, his daughter brought it into the gallery to see if they could sell it for her. It has since been purchased, but even the digital version of the work still moves Betsy.

It is evocative and powerful, a poignant reminder of Jack’s uncanny ability to capture the feeling of a moment as deftly as its imagery. “You can see yourself standing there,” she says through tears. “You can feel it.”

Tucked quietly away in the bottom right corner of the painting are two silhouettes, the only witnesses to a captivating late-night scene that glistens with an ethereal combination of moonlight and bulbs from the Mardi Gras arch reflecting off the rain-soaked pavement.

“His nighttime paintings were really something,” says Betsy. “He was also brilliant at capturing that shift-of-light moment from dusk to dark.”

His other notable works are snapshots from everyday life that elicit a familiarity and commonality with the subject, such as “Catching Up on Current Events.” An otherwise mundane image of an employee reading the local paper becomes with the stroke of Jack’s brush a poignant, watershed life moment simply because of its abject simplicity and ease.

Jack was also fond of capturing Galveston landmarks. “But his landmarks weren’t just Ashton Villa or Moody Mansion. It was Sonny’s,” Betsy says, referring to the longtime local favorite eatery on 19th Street. “He knew old Galveston like he knew old New Orleans.”

Betsy attests that Jack’s accomplishments were not merely aesthetic but technical, too. “He started out as a watercolor artist,” she says. “But later shifted into oil. And that is a difficult transition for any artist to make—the depth, the brushstrokes are completely different.”

Still for Betsy, his watercolors are often the most engaging. “In the watercolors, you can really see the architect in his work, how he constructed the piece.”

This month, the final chapter of Third Coast Gallery’s long history will come to an end, as Christina and her husband have regretfully decided to sell the building on Mechanic Street. The gallery will close permanently at the end of the month, although what remains of Jack’s work will still be available for online purchase.

In celebration of Jack Morris, his work, and his life, Third Coast will host a farewell celebration during the July ArtWalk on the 17th from 5:30-9pm.

Since COVID prevented the gathering of friends after Jack’s passing, Betsy says, “This is really our memorial for him. We can finally give him a proper farewell.”

Despite the sorrow that naturally accompanies saying goodbye to a friend, father, and his storied gallery, his loved ones can revel in the fact that the indelible mark Jack Morris made on Galveston will never be erased.