The women’s suffrage movement is often distilled to one date—August 18, 1920, the day the United States Congress ratified the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. But this monumental day was the culmination of nearly fifty years of activism, protests, campaigns, letter-writing, parades, and any other demonstration women could muster to make their voices heard. And counted.

Interestingly, women’s suffrage was as much a societal issue as a political one. The country was approaching its 150th birthday by the time women were given the vote, and most women had been conditioned to believe that the societal construct placed upon them was just.

Thus, women of the movement were tasked with convincing not only politicians but also other women of their worth, value, and intrinsic rights. This took decades, and it required the efforts of women who devoted their entire lives to the cause.

Minnie Fisher Cunningham was an island transplant who arrived in 1907. Galveston was literally knee-deep in a solution of saltwater and silt, not yet halfway through the grade-raising. However, the magnificent engineering of the task did not dampen but rather emboldened the local population.

The city had been working furiously since the 1900 Storm to reclaim its national reputation as an urban oasis, a paradise both in form and culture, and the opening of the Houston Ship Channel was still seven years away. Commercially, Galveston was contentedly continuing its reign as the nation’s premiere southwest port, buoyed by ingenuity, technology, and some of the most intelligent and successful men in the country.

Culturally, the perpetual infusion of immigrants and European influence, as well as unbridled access to information from all far-flung corners of the world, quilted a diverse community who matched their commercial counterparts in their quest for progress, innovation, and new ways of thinking.

Culturally, the perpetual infusion of immigrants and European influence, as well as unbridled access to information from all far-flung corners of the world, quilted a diverse community who matched their commercial counterparts in their quest for progress, innovation, and new ways of thinking.

Galveston therefore provided a perfect incubator for the mind and ambition of Minnie Fisher Cunningham, who eventually carried her island-born influence all the way to Washington, D.C.

Minnie Cunningham was not a stranger to Galveston when she arrived with her husband. The handsome B.J. Cunningham was a Galveston attorney who had relocated to Huntsville, the city where Minnie had recently taken her first job as a pharmacist after completing medical school at the University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) in Galveston.

Born in New Waverly on March 19, 1882, Minnie Fisher received her early education and influence from her mother Sallie Fisher, who believed that all women should be well-educated and self-reliant. At the age of sixteen, Minnie passed the state examination and earned her teaching certificate.

A year later, she decided against teaching as her profession and applied to UTMB. Minnie was enrolled as a student when the Great Storm hit the island.

Amid the aftermath, Minnie and her mother held a fundraiser in New Waverly to raise money for disaster aid to Galveston. The very next year, Minnie Fisher became the first woman from UTMB and only the second in Texas to graduate with a Masters Degree in Pharmacology.

Minnie’s political interests were also stirred at an early age. Her father Horatio Fisher was twice elected to the House of Representatives of the Texas Legislature (1857-59, 1879-81), and Minnie often accompanied him to political meetings in Huntsville.

After abandoning her pharmacy career to marry B.J. Cunningham in 1902, Minnie was fortuitously given her first glimpse of the campaign trail, and her political interests were reignited when her husband ran a successful race as a reform candidate for the position of Walker County Attorney.

In 1905, the couple moved to Houston. Shortly thereafter, B.J. acquired a position with the Galveston-based American National Insurance Company (ANICO), and Minnie immediately recognized that the island city was fertile ground on which to spread the ideas and philosophies that had been forming in her mind since childhood.

She immediately joined the Women’s Health Protective Association (WHPA), comprised of women who by day rallied their peers for causes such as clean streets, clean water, city parks, and regulations for dairy farmers. In the evening, unbeknownst to many and spoken of by no one, they wielded their influence at the dinner table and in the drawing room, extolling their ideas for positive change to their powerful husbands.

For many women including Minnie Fisher Cunningham, social reform was their entrance into the cause of women’s suffrage. It not only provided a unifying platform with other like-minded women but also instilled confidence in their individual abilities to positively influence their community.

The more they successfully negotiated social restraints for their local causes, the more they became aware that the limitations they faced at the national level could too be changed.

In 1910, Minnie Fisher Cunningham became a founding member of the Galveston Equal Suffrage Association (GESA) and served on the board’s executive committee. Two years later, she was elected to her first of two terms as president of the association.

Cunningham was a natural leader, tireless and incredibly motivated. Using the GESA forum, she honed her oratorial skills by accepting public speaking engagements and opportunities to address groups of legislators.

Meanwhile, the Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) had been recently re-energized by the election of a new president, Annette Finnigan, who quickly learned about the rising star in Galveston. Finnigan recruited Cunningham to work for TESA as a lobbyist and field organizer and soon began grooming her for greater things. When Finnigan retired in 1915, Cunningham was easily elected as her successor.

Minnie served four consecutive terms as President of TESA (1915-1919), during which time she expanded membership to more than 10,000 women with headquarters in every legislative district. Using her keen diplomacy and unwavering conviction, Cunningham also built a formidable lobbying presence in Austin.

Despite the conservative climate of the Texas Legislature, she managed to play both sides against the middle, assuring each party that women’s votes would help them win elections.

Despite the conservative climate of the Texas Legislature, she managed to play both sides against the middle, assuring each party that women’s votes would help them win elections.

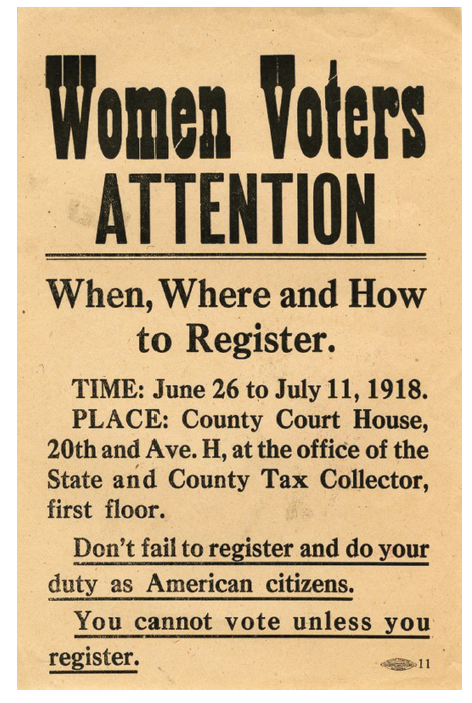

Cunningham also maneuvered political unrest amid the state’s Democratic Party to gather enough support for a 1918 bill which granted women the right to vote in state primary elections. Subsequently, Texas joined Arkansas as the first states to allow women at the polls.

Even before the bill was passed, Cunningham’s work caught the attention of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA), and Minnie journeyed from Texas to Washington at their behest on several occasions. In 1917, she met with U.S. Senator from Texas Morris Sheppard in his D.C. office to garner support for an equal suffrage amendment.

She and other NAWSA members inundated their representatives with telegrams. Cunningham pressured Texas newspapers to print editorials in favor of women’s suffrage.

On January 10, 1918, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the first version of the 19th Amendment, but days later, it failed in the Senate. The Texas State Legislature passed a state amendment for full suffrage for women in January of 1919, but it was subject to referendum by state voters and failed.

Cunningham and her cohorts remained diligent, but when the 19th Amendment was finally passed by both the House and the Senate in late spring of 1919, their work was still not done.

Three-fourths of state legislatures—36 out of then 48—had to vote in favor of ratification for the Amendment to be accepted into the Constitution, and Minnie immediately returned back to Texas to convince her legislature to ratify.

As a result of her efforts, Texas became the first southern state to ratify the 19th Amendment on June 28, 1919, and Minnie left on a campaign tour to lend her assistance to other states. More than a year later, the 36th state cast their approval and the 19th Amendment was finally, permanently in place.

Cunningham spent the rest of her life as an activist for social reform and a promoter for women’s rights. She moved to Washington, D.C. and helped found the National League of Women Voters (LWV).

In 1927, she returned to New Waverly and became the first woman in Texas to run for U.S. Senate in 1928. Cunningham later became involved in anti-poverty causes through her work as associate editor and then editor of the Texas A&M Agricultural Extension Service from 1930-1939.

In 1944, she ran for Governor of Texas and finished second out of nine candidates. Then in 1960, the 78-year-old Minnie set up a campaign office for John F. Kennedy in Walker County; it was the only county in the state that Kennedy won. In recognition of her achievement, Cunningham attended Kennedy’s 1961 inauguration as an invited guest.

Throughout her later years, Minnie battled a heart condition and other health problems, but she continued her work despite the physical decline. Then in 1964, she broke her hip.

Now completely immobile, Minnie was deprived of her life’s work. Before the year was out, she died of congestive heart failure on December 9, 1964.

In a 1940 interview, Eleanor Roosevelt recalled the second annual convention of the LWV, held almost twenty years prior. Cunningham was the guest speaker, and although decades had passed, Roosevelt still remembered her speech.

With her trademark conviction, with her purpose and talent both cultivated in Galveston, Minnie made the audience feel “that you had no right to be a slacker as a citizen, you had no right not to take an active part in what was happening to your country as a whole.”