The Strand is a brilliant concoction of

a flagrant history and a reimagined future. It is a street that has survived

catastrophe, economic collapse, and traveled the most treacherous journey of

all, through the merciless sands of time. The portion of Galveston’s Strand

Street between 20th and 25th Streets is called simply,

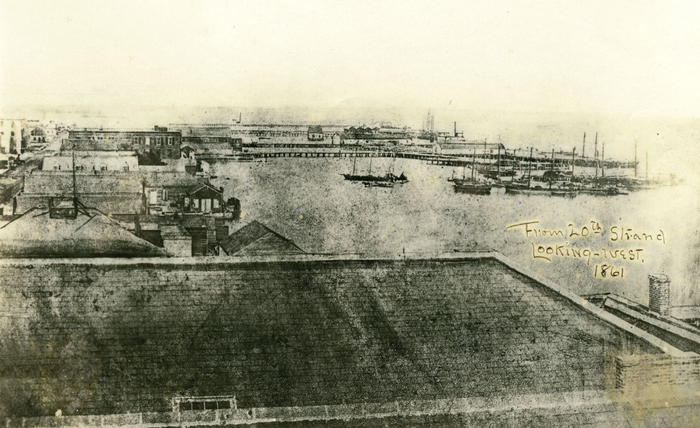

“The Strand.” It runs east to west, parallel to the harbor only a block away,

and in the late 19th century when that harbor was a commercial mecca

of shipping, banking, wholesaling, and trading, The Strand was dubbed, “the

Wall Street of the South.”

Today, almost all of the ornate Victorian buildings from that time still

stand, and the street is all at once an historical monument and a modern

playground, ripe with the creativity of retailers and chefs, lined with

novelties, exotics, parks, and taverns. The evolution of The Strand over nearly

two centuries is a testament to the dedication of the Galveston community to preserve

its history while also forging a path to the future. But its very existence is

ultimately due to the Island’s geographical advantage as a natural port.

Galveston Island is 32 miles long and not even two miles across at its

widest point; it sits just off the coast of Texas fifty miles from Houston.

Toward the eastern side of the island between the shore and the mainland is

nestled another, smaller land mass called Pelican Island. The positioning of

these two islands creates a perfect harbor along Galveston’s northern

shoreline, a fact that was first capitalized upon by the pirate Jean Lafitte at

a time when Texas was still a part of Mexico.

Galveston Island is 32 miles long and not even two miles across at its

widest point; it sits just off the coast of Texas fifty miles from Houston.

Toward the eastern side of the island between the shore and the mainland is

nestled another, smaller land mass called Pelican Island. The positioning of

these two islands creates a perfect harbor along Galveston’s northern

shoreline, a fact that was first capitalized upon by the pirate Jean Lafitte at

a time when Texas was still a part of Mexico.

Lafitte seized control of the Island from the indigenous Karankawa tribe

in 1817, but he remained only until 1821 when the United States Navy, in an

alliance with the Mexican government, let him know that his presence was no

longer required. After Lafitte’s exit, a small trading post was established in

1825, but the island would remain mostly vacant for another decade.

Meanwhile, an illiterate fur trader from Quebec was making his way

south, learning to read and write and establishing himself as a keen and adept

merchant. In 1829, Michel B. Menard applied for citizenship to Nacogdoches, and

upon arriving in Texas he formed a powerful alliance with Juan Seguin as his

Mexican headright. Land in Texas could only be purchased from a Mexican citizen

and Seguin, who would years later fight beside Texans in their war for

independence, was able to secure for Menard land speculations totaling nearly

40,000 acres by 1834. Of those were 6,640 acres on Galveston Island.

Meanwhile, an illiterate fur trader from Quebec was making his way

south, learning to read and write and establishing himself as a keen and adept

merchant. In 1829, Michel B. Menard applied for citizenship to Nacogdoches, and

upon arriving in Texas he formed a powerful alliance with Juan Seguin as his

Mexican headright. Land in Texas could only be purchased from a Mexican citizen

and Seguin, who would years later fight beside Texans in their war for

independence, was able to secure for Menard land speculations totaling nearly

40,000 acres by 1834. Of those were 6,640 acres on Galveston Island.

Strategically located on the part of the island with the highest

elevation, the six thousand acres also included the land along the harbor

front, making it ideal for development of a port city. Because of governmental

stipulations that required permission from the President, however, Menard was

not able to develop it until Texas won its independence from Mexico in 1836.

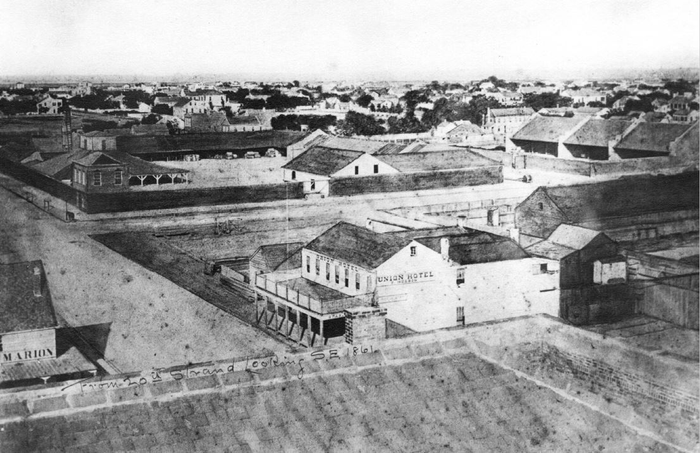

Following the Republic’s victory, that same year the first American

settlement of Galveston formed on the east portion of where Strand Street is

today, on the current site of the University of Texas Medical Branch. It was a

“city” comprised entirely of tents, protected from the rising tide of the

harbor by large ridges of shale.

By 1838, Menard was able to complete the organization of the Galveston

City Company, and the first lot was sold on April 20th of that year.

By 1838, Menard was able to complete the organization of the Galveston

City Company, and the first lot was sold on April 20th of that year.

Aside from some minor modifications after The Great Storm of 1900, the

original plat of the city has predominantly stayed the same. Numbered streets

run north to south along the length of the island, and lettered streets run

east to west from the harbor to the Gulf. Downtown in the commercial district,

the lettered streets were also eventually named.

At

the city’s inception, Avenue A (present day Harborside Drive) was basically the

harbor shoreline, meaning that it was almost always entirely underwater. On the

very first plat of the city of Galveston, Avenue B was called Common Street.

But that was the first and only time it would bear that name.

Galveston’s Strand was named after the Strand in London. Linguistically

the word itself is somewhat fitting, as it is derived from the Old English strond, which means “along the edge of a

river;” London’s Strand once ran along the River Thames. More importantly, the

nomenclature indicated high aspirations for the future of the island city, as

its namesake in the 19th century was a lively thoroughfare of

commerce and culture.

The Port of Galveston was established as instantly as the city began,

and The Strand embarked upon its figurative ascent to

prominence, although it would take a full thirty years before it was even

paved. In the early days of Strand Street, it was highly susceptible to high

tides and rain which created a bog of mud and slime. Oyster shells were dumped

onto the street in mass quantities in an attempt to alleviate the marsh-like

conditions, but they were relatively ineffective after only a few days of being

crushed under horse hooves and wooden wheels.

But even these conditions did not deter the inevitable rise of The

Strand. Fueled by Texas’ prolific production of cotton, and prompted further by

all of the potential garnered from an international port, the success of

Galveston and its port were imminent. Warehouses, commission houses, merchants,

traders, seamen, shipbuilders, and the like were all drawn to the lucrative

endeavors that Galveston had to offer.

But even these conditions did not deter the inevitable rise of The

Strand. Fueled by Texas’ prolific production of cotton, and prompted further by

all of the potential garnered from an international port, the success of

Galveston and its port were imminent. Warehouses, commission houses, merchants,

traders, seamen, shipbuilders, and the like were all drawn to the lucrative

endeavors that Galveston had to offer.

Along the north side of the street, buildings were built on pilings that

jutted out over the water which covered Avenue A. Storeowners could ship and

receive right out of their back doors, and anecdotes tell of employees going to

the second floor on their breaks and fishing out of the window.

One of the first merchants to build on the strand was John M. Jones, who

built a two-story wooden structure near 23rd Street in 1839. He

placed a sign over the door of his business that read, “No. 8 Strand,” and he

was known as such for many years. Jones was a watchmaker and a jeweler, the

first in Galveston, “and repaired and put in order most of the timepieces in

this section of the republic of Texas” (News,

25 October 1908).

George Ball, who would go on to become one of Galveston’s most notable

businessmen, arrived about that time as well. He was also a jeweler and

watchmaker and opened a business with his brother Albert on Market Street, but

soon the business expanded and moved to the Strand.

In March of 1839, the very first city council of Galveston met in a

two-story wood-frame building near the intersection of Strand and 17th

Street. Later the building was moved a few blocks west, to the south side of

the street between 21st and 22nd.

Another early transaction of the Galveston City Company was the sale of

the lot on the northwest corner of Strand and 23rd Street to Moro

Philips, who erected a two story building larger than any other at the time.

Known as Moro Castle, its foundation was pilings that rose four or five feet

above the street. County records show that in 1840 Moro purchased a license for

“two establishments retailing liquor, ten-pin alley and two billiard tables.”

After retiring from Galveston Moro returned to his home of Philadelphia, and

when he passed left behind an estate valued at $4 million.

Another early transaction of the Galveston City Company was the sale of

the lot on the northwest corner of Strand and 23rd Street to Moro

Philips, who erected a two story building larger than any other at the time.

Known as Moro Castle, its foundation was pilings that rose four or five feet

above the street. County records show that in 1840 Moro purchased a license for

“two establishments retailing liquor, ten-pin alley and two billiard tables.”

After retiring from Galveston Moro returned to his home of Philadelphia, and

when he passed left behind an estate valued at $4 million.

One of the first brick buildings built on the Strand was situated at the

corner of 25th Street. This was the building where Gail Borden, of

condensed milk fame, would conduct his first food preservation experiments.

From here he put up his first product known as Borden’s “compressed meat

biscuit.” Unfortunately Galveston could not contain his genius, and he left in

the 1850s to pursue his eventual, enormous success.

As the commercial district began to flourish, likewise its perimeter

began to burgeon with residential areas. In place of the original “tent city”

east of the district, a neighborhood sprang up of wooden homes and shotgun

houses. In addition to permanent residences, the Strand and adjacent streets

were lined with boarding houses for sailors, travelers, and immigrants.

Even before the city was established as a commercial port, Galveston was

claimed as a gateway to Texas for European immigrants. The influx increased

even further upon the independence of Texas, and it became a critical element

in Galveston’s identity. The infusion of international cultures upon the

general population from the very onset of the city gave birth to an eclectic

diversity and marked European influence in both its economy and architectural

designs.

As the newest, largest, and fastest growing

city in Texas, Galveston and its gem of a port were well on their way to making

history, and the city boasts a long list of firsts in Texas. In just its first

decade of existence, Galveston became home to the Texas’ first post office,

naval base, bakery, cotton compress, and grocery store. By 1850, the city had

gone from zero residents to over five thousand, and over the next thirty years,

despite war and abandonment, that number would more than quadruple.

Chapter 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7- 8 - 9 - 10 -11 - 12