Many times in the modern world of

development, beauty is sacrificed for convenience, as if it were an adequate

substitute. Stark, grey freeways are noble in their pursuit of speed, thus

often preferred to the winding back roads despite their scenic splendor. But

sometimes, a community gets it right. Every now and then, a group of people

refuse to allow the impeccable standards of historic architecture to submit to

the sterility of modern city planning, choosing instead another perspective

that seeks to reinvent instead of raze.

In 1970 Galveston,

this was assuredly a widespread mindset that had been cultivated over the

previous decade by city officials, the Galveston Historical Foundation, and the

Galveston Junior League, but the trio had yet to entirely suppress a penchant

for bulldozing historic buildings for quick cash flow purposes such as parking

lots. Revitalizing the Strand was a project

that would require cohesion, vision, and diligence.

An attorney from Washington, D.C. named Peter Brink was chosen to lead the collective

efforts along the Strand. He was already

somewhat familiar with Galveston;

the city’s remarkable potential for restoration had been recognized in the

nation’s capital for quite some time.

Brink

was made interim director of the Galveston Historical Foundation, and went

quickly about reorganizing the group to better suit the scope of the Strand concept. Lacking wholly in restoration experience,

Brink compensated with both the legal background required to create a revolving

fund that would be necessary to prompt investment in the historic architecture,

as well as a forward-thinking and ultimately prophetic vision for the future of

the street.

Heretofore, preservation in the city had mainly focused on house

museums, but Brink was adamant that this venture be recognized as one that

would actually use the buildings.

“[The goal is] to save historic buildings and to adapt them to current needs,”

he said on behalf of the GHF to the Houston

Post in 1973.

“[We

will] recycle our historic buildings to bring them fully into the mainstream of

Galveston-Houston life… I can see townhouses and apartments as well as shops

and restaurants and bookstores on the street.”

But even before one building was sold, a burgeoning local art scene was

working to perpetuate the Strand as a center

of cultural celebration. Festival on the Strand

was started in 1972 and continued throughout the decade. The idea was conceived

by the Galveston County Cultural Arts Council, who aimed “to bring great

visibility to hundreds of the region’s most accomplished but often unknown

artists, and to suggest new uses for the 19th century buildings in

the Historic Strand District.” Over the course of a weekend in May, Strand and Mechanic Streets were lined with exotic food

vendors and arts and crafts; a film festival and live dance and theatre

performances provided additional entertainment.

Aided by a $200,000 donation from the Moody Foundation and another

$15,000 from the Kempner Foundation, Brink and the GHF successfully established

a revolving fund in April of 1973, which would serve to protect the fate of the

buildings on the Strand and reserve them for

new uses.

Buildings

would be purchased with the fund and re-sold as quickly as possible to

investors; the money from the sale would return to the account and be recycled

to purchase another structure. In addition to the buildings’ ability to

generate income, their purchase was incentivized with significant tax shelters,

as long as the purchase met a set of certain set of criteria set forth by the

Secretary of the Interior.

The

criteria designated the types and uses of the buildings that were eligible for

the tax breaks, and they also required substantial rehabilitation. While the

investors were motivated by the financial benefit of complying, their adherence

subsequently assured a prompt renovation and occupation of the buildings.

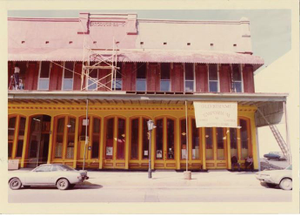

In 1974, the very first retail store was opened on the Strand.

Housed in the Mallory Produce Building

between 21st and 22nd Streets, the Old Strand Emporium

led the charge, its solitary yet fearless existence paving the first step of

the Strand’s modern reimagining. It would

prove to be a gamble that would find the homespun store on the right side of

history—it remains to this day and now holds the title of the oldest store on

the Strand.

In 1974, the very first retail store was opened on the Strand.

Housed in the Mallory Produce Building

between 21st and 22nd Streets, the Old Strand Emporium

led the charge, its solitary yet fearless existence paving the first step of

the Strand’s modern reimagining. It would

prove to be a gamble that would find the homespun store on the right side of

history—it remains to this day and now holds the title of the oldest store on

the Strand.

The

1970s would see the birth of another Strand

legend when LaKing’s Confectionery was opened in 1977. Replete with a vintage

soda fountain feel and enough sugar under one roof to sweeten all the tea in

the south, forty years later it remains one of the street’s most popular

destinations.

The next line of action for the Galveston Historical Foundation was to

commission a survey of the Strand that would

thoroughly outline strategic blueprints for increasing the visibility of the

street’s ongoing renaissance and attracting foot traffic to the area. The

planning firm of Venturi and Ranch generated the “Action Plan for the Strand” in 1975, a comprehensive assessment that outlined

every intricacy of the project from signage to parking and traffic control, as

well as color schemes and ideas for interior renovations.

The action plan also addressed the Strand’s

most significant disadvantage—a reputation which the 20th century

had noticeably tarnished. In concordance with the study, University

of Houston students conducted a survey

that revealed that the Strand’s location, and

even its mere existence, were practically unknown to both visitors and

residents. And the ones who did know about it equated the street with crime and

perceived it as a dangerous place to be. “As the Strand is no longer in the

mainstream of Galveston

activity, it must reach out to attract potential visitors and aggressively

change its image,” the firm stated.

As implementation of the Venturi and Ranch plan continued, the efforts

to legitimize Galveston’s

downtown were substantially bolstered in 1976 by the renovation of the Blum

building one block away on Mechanic

Street. Island enthusiast and philanthropist

George P. Mitchell spent $12 million dollars to transform the former warehouse

into a reincarnation of Galveston’s

first hotel, the Tremont House.

That

same year, the Strand District was awarded an upgrade from a place on the

National Register of Historic Places to that of Landmark status, and by the

close of 1977, over $3 million in private investments had been made along Strand Street.

The happenings on the Strand in the

late 1970s garnered nationwide attention, so much so that they captured the

attention of the famed Kresge Foundation. Established in 1924, the foundation’s

endowment today surpasses $3 billion, and at the time its coveted grants were

exclusively awarded to local communities for the particular purposes of

construction and renovation of historic buildings. In 1979, they gifted $25,000

to the Strand project, which in turn inspired

grants from other well-known entities such as the Brown Foundation, the

Rockwell Funds, Atlantic Richfield, and Houston Oil & Mineral.

By the close of the decade, the minutiae of scattered, subtle changes

along the Strand finally began to coalesce

into tangible, obvious progress. Peter Brink stated in a 1979 interview that

“at some point, I’d no longer walk down the street thinking, ‘Is it going to

work?’”

The

plan was indeed working, but most importantly it had pushed past the boundaries

of preservation and transformed the Strand

into living history. No longer was it forgotten and abandoned, precariously

exposed to the sands of time and the whimsies of man, but neither was it

enshrined to be glimpsed at only from afar. Because of the GHF and its

visionary-for-hire, Galveston’s

historical relevance was now, and would forever remain, both an integral facet

of the city’s economy and a crucial part of the island’s identity.

This

is the 10th monthly segment on the history of The Strand.

Read the first nine chapters of the Strand

Chronicles online at GalvestonMonthly.com and on our Facebook page.

Chapter 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7- 8 - 9 - 10 -11 - 12