In 1920, Galveston’s

commercial district was still reeling from the formation of the Port of Houston

that had abruptly diverted the island’s relevance northward, but for a while

longer it did manage to hold on to its status as the top cotton port in the

nation. Subsequently the Strand emitted but a glimpse of its former glory as

the liaison between Galveston’s

port and the rest of the world.

Although still inhabited by grocers, cotton

factors, and commission houses, the street had taken on an air of solemnity,

and its newsworthy mentions were bleakly limited to the daily costs of produce.

Sentiment refused to relinquish the Strand’s

designation as a business district, but without business it became a street in

exile, all but forgotten—the star player had been banished to the bench.

Although still inhabited by grocers, cotton

factors, and commission houses, the street had taken on an air of solemnity,

and its newsworthy mentions were bleakly limited to the daily costs of produce.

Sentiment refused to relinquish the Strand’s

designation as a business district, but without business it became a street in

exile, all but forgotten—the star player had been banished to the bench.

However, the city itself was far from being

undone, thanks to a government initiative that was meant to be restrictive but

instead became paradoxically fortunate for Galveston. The Eighteenth Amendment went into

effect on January 16, 1920, definitively outlawing both the sale and

consumption of alcohol nationwide. Most people know it as Prohibition, but in

the unsinkable island city it was seen as a prime opportunity.

In fact, Galveston County

had actually proclaimed itself dry in 1918 as a testament of support for the

growing movement against alcohol. Which means that by the time the federal

government got around to formally enacting the legislation, enterprising

individuals in Galveston

had already figured out how to smuggle it in.

And just as the Galveston’s location had served the

legitimate entrepreneurs of the 19th century, so did it also prove

advantageous to the illicit ones. The booze-laden islands of Jamaica, Cuba,

and the Bahamas were merely

a Gulf of Mexico away, and schooners overloaded with as many as 20,000 cases of

liquor began dropping anchor off the Galveston

shore as early as 1919.

Thirty-five miles southwest of the island was

a rendezvous point known as Rum Row. There, it was loaded onto smaller, more

mobile crafts and delivered most often to points along the deserted beaches on

the west end. On other occasions, more brazen operations took advantage of Galveston’s sleepy wharf,

where they would manage to unload it onto an isolated pier along with some of

the port’s few remaining imports.

Although the beach landings were more

discreet, the port deliveries had the advantage as far as expediently securing

the cargo went. On the Strand, less than a

block away from the docks, were a number of prime storage opportunities in the

form of vacant buildings and empty upper levels with back alley doors and a

desperate need for tenants. Although no documented paper trail exists for these

agreements, Island lore maintains that the second floor of the James Fadden

building at 2410-12 Strand was used as a

warehouse by the Downtown Gang.

Their territory was north of Broadway, while

the area south of this center dividing line was controlled by the Beach Gang.

Their territory included Seawall

Boulevard, which happened to be where two Italian

immigrants named Sam and Rose Maceo had secured employment as barbers—one

inside the Hotel Galvez, the other inside Murdoch’s Bathhouse.

Their territory was north of Broadway, while

the area south of this center dividing line was controlled by the Beach Gang.

Their territory included Seawall

Boulevard, which happened to be where two Italian

immigrants named Sam and Rose Maceo had secured employment as barbers—one

inside the Hotel Galvez, the other inside Murdoch’s Bathhouse.

After Rose Maceo provided a temporary hiding

spot for a stash of liquor, the brothers became fast friends and business

partners with Beach Gang leaders Dutch Voight and Ollie Quinn. Together they

opened the Hollywood Dinner Club on 61st

Street, revealing the city’s insatiable appetite

for gambling and adding another vice to their list of endeavors.

By the late 1920s, the upper echelon of the Galveston gangs had gone

to the wayside via prison or impending prosecution, and the Maceo’s had

garnered complete control of the city's underworld. But it was only the

underworld in the context of the rest of the country—in Galveston, it was the economic stalwart.

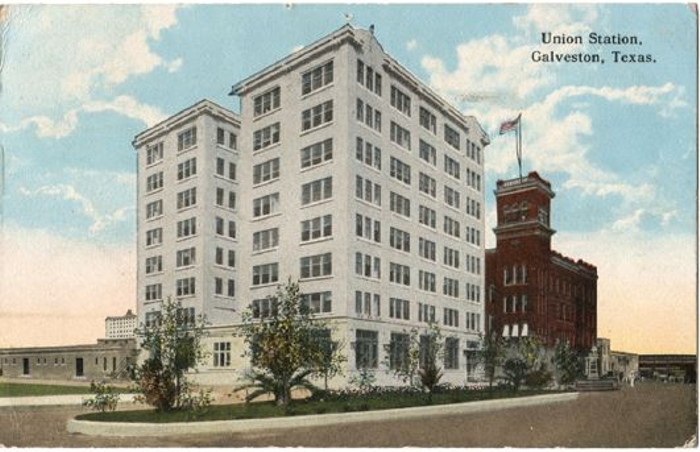

Visitors flocked to the island and the hotels

were full, even in the wintertime. All methods of transportation to the island

were taxed, especially the passenger trains. This led to the construction of a

new depot and the placement of the final, decorative piece onto the Strand’s architectural showcase.

At the corner of 25th and Strand, where the rail yard ended and met the commercial

district, a small, four story depot was constructed in 1914. With Galveston’s

significant surge of growth due to its popularity as an entertainment

destination, the station proved inadequate and in 1931, the east half of it was

demolished to make way for a massive structure that consisted of one

eleven-story tower sandwiched between two eight-story towers. Technically the

new construction was an “addition” to the original building, but its

resplendent profile justified no such technicality.

At the corner of 25th and Strand, where the rail yard ended and met the commercial

district, a small, four story depot was constructed in 1914. With Galveston’s

significant surge of growth due to its popularity as an entertainment

destination, the station proved inadequate and in 1931, the east half of it was

demolished to make way for a massive structure that consisted of one

eleven-story tower sandwiched between two eight-story towers. Technically the

new construction was an “addition” to the original building, but its

resplendent profile justified no such technicality.

The old depot was a modest, stone structure.

The new one was embellished with a design that defines the Art Deco movement of

the 1930s, and it became the headquarters of the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railroad. Their

offices were housed on the upper levels of the building, while the Union

passenger train station on first floor was outfitted with marble floors, lofted

ceilings, and mahogany benches.

With its eastward facing entrance that

conclusively halts the westward progress of Strand Street, it provides today a

strangely fitting bookend to the veritable kaleidoscope of architecture, but at

the time of its construction it was more noted for providing direct access to 25th Street,

one of the main thoroughfares leading to Seawall Boulevard and its opulent hotels

and casinos.

Although just as feverish and lucrative, the

economic climate of Galveston

had certainly shifted. No longer did out-of-towers inquire about the port or

cotton facilities, only of the casinos and speakeasies. When the 1930s brought

the voracious return of prostitution after a brief hiatus during World War I, Galveston’s trifecta of

vice was complete and it became the golden ticket of the southwest.

Although just as feverish and lucrative, the

economic climate of Galveston

had certainly shifted. No longer did out-of-towers inquire about the port or

cotton facilities, only of the casinos and speakeasies. When the 1930s brought

the voracious return of prostitution after a brief hiatus during World War I, Galveston’s trifecta of

vice was complete and it became the golden ticket of the southwest.

The Strand, unfortunately, saw the port lose

its cotton ranking to Houston in 1931, and even

though it gained it back the following year, that would forever be the last

time Galveston’s

port would grace the record books. Over the next two decades, it was the Maceos

alone that would carry the financial well-being of the city. Even through the

Great Depression and World War II, their underworld sustained the island and

shielded it from the desperate circumstances that plagued the rest of the

country.

In 1951, Sam Maceo succumbed to cancer; less

than two years later, Rose died as well. Their controlling  interests had been

passed to their nephews through marriage, the Fertitta brothers. But the 1950s

created the perfect storm for the passing of an era. The trust and respect

gleaned by the Maceos from the city and their clout with state officials could

not be duplicated, in Nevada gaming was now

legal and devoid of risk, and in Texas, the

newly elected attorney general, Will Wilson, was determined to take down Galveston to advance his

own career. In 1957, he finally succeeded.

interests had been

passed to their nephews through marriage, the Fertitta brothers. But the 1950s

created the perfect storm for the passing of an era. The trust and respect

gleaned by the Maceos from the city and their clout with state officials could

not be duplicated, in Nevada gaming was now

legal and devoid of risk, and in Texas, the

newly elected attorney general, Will Wilson, was determined to take down Galveston to advance his

own career. In 1957, he finally succeeded.

If what was left of Galveston

after the Texas Rangers finished their raids was a ruined sense of identity and

hopeless outlook for the future, what was left of the Strand

was a hollowed out shell of significance. For thirty years, it had been passed

over for the speakeasies on Market

Street and the brothels of Postoffice, mere blocks

away. Now, with not even guilt by association to speak of, the future seemed to

be one of minimal mediocrity. But as with all things that are destined to be

timeless, the Strand’s greatness could only be

temporarily hidden.

Chapter 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7- 8 - 9 - 10 -11 - 12