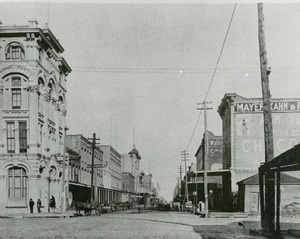

The Strand

of the late 19th century, with its dapper merchants and brick

buildings and foreign travelers, was assuredly able to produce no less than a

picturesque tableau at any given moment of its existence. Although today these

visions are mostly relegated to the imagination, the catalogue of rampant

activity happening all at the same time, on the same street, is sufficient

enough to easily conjure a kaleidoscope of quintessential historic scenes.

The “Wall Street of the South” had always

been a street of bankers and wholesalers, commission and auction houses, but

growth begets growth in any form. Along with the readily available wealth of Galveston residents, the city was flourishing also as a

port of immigration—by the end of the 19th century it would even

surpass Ellis Island with the number of immigrants for whom the Island served as a gateway to opportunity.

Thus against this backdrop of commerce and

immigration was a thriving dry goods market. Carriage and furniture makers,

agricultural warehouses, printers and painters, grocery and liquor dealers,

candy and coffee makers lined the Strand, as

well as eight newspapers, agents that helped travelers secure passage via steam

and sail ships, and a French outlet named Pellegrini and Company that sold

ready-made clothing as well as other luxuries like artificial flowers and

perfume.

The Strand

at this time was also no stranger to the curious, with street entertainers such

as a man who would eat glass, and apothecaries peddling their mysterious

potions. Even the fabulously dressed Oscar Wilde made an appearance in 1882,

inspiring awe in onlookers as he strode toward the location where he was to

make a speech on “Decorative Art.”

The Parade of Butchers was a New Year’s Day

custom that by all accounts originated in Galveston

in Civil War days, and it continued throughout the 1880s. Local butchers donned

masks and outlandish costumes and rode haggard horses and mules down the

street, making stops at all the taverns along the way. This decade also saw the

initiation of annual Mardi Gras parades that careened down the Strand with

pageantry and spectacle, displaying Galveston’s

elite atop fanciful floats and filling downtown with the raucous revelry of

brass bands.

The Parade of Butchers was a New Year’s Day

custom that by all accounts originated in Galveston

in Civil War days, and it continued throughout the 1880s. Local butchers donned

masks and outlandish costumes and rode haggard horses and mules down the

street, making stops at all the taverns along the way. This decade also saw the

initiation of annual Mardi Gras parades that careened down the Strand with

pageantry and spectacle, displaying Galveston’s

elite atop fanciful floats and filling downtown with the raucous revelry of

brass bands.

Additionally, the international trade brought

sailors and seamen of all nationalities and ethnicities to the humble coastal

town, creating a demand for exotic cuisines and foreign niceties that were all

but lost to towns of the interior. This melting pot mentality also manifested

itself prominently in the architecture of the Strand,

the designs of which were influenced by architectural genres from all over the

world. Galveston’s

haven of commercial activity attracted all sorts of genius from every

profession looking to invest their talents for fortune, not the least of whom

were up-and-coming architects, walking by the empty lots that would one day

make them immortal.

With a population of twenty-two thousand in

1880, Galveston was the largest city in the

state of Texas.

It was a modern and cosmopolitan city, prosperous and beautiful, sophisticated

and grand. In 1881 alone, over thirty-eight million dollars worth of

merchandise exchanged hands on the Strand.

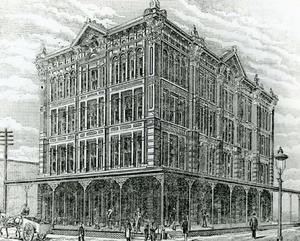

That same year, Nicholas J. Clayton, who had

emerged on the Strand as the first full-time architect in Galveston with his

construction of the Gulf, Colorado, & Santa Fe Railroad Building on the

corner of 25th Street, stunned the Strand yet again with one of his

most detailed works, the Greenleve-Block building (2314-2318 Strand) for

Greenleve, Block, and Company, one of three of the largest wholesale dry goods

firms in town. The monstrous, four-story building boasted an intricate cornice

that ran the entirety of the roofline, giving an appearance of a fifth floor.

Three large bays opened onto the street, the entrances embellished with

detailed carvings etched into the stone that depicted the Texas star, the letter “G” for Greenleve,

and street numbers. Upon its completion, the genius of Nicholas Clayton was

considered unrivaled and he was soon sought-after by the wealthiest men in

town.

That same year, Nicholas J. Clayton, who had

emerged on the Strand as the first full-time architect in Galveston with his

construction of the Gulf, Colorado, & Santa Fe Railroad Building on the

corner of 25th Street, stunned the Strand yet again with one of his

most detailed works, the Greenleve-Block building (2314-2318 Strand) for

Greenleve, Block, and Company, one of three of the largest wholesale dry goods

firms in town. The monstrous, four-story building boasted an intricate cornice

that ran the entirety of the roofline, giving an appearance of a fifth floor.

Three large bays opened onto the street, the entrances embellished with

detailed carvings etched into the stone that depicted the Texas star, the letter “G” for Greenleve,

and street numbers. Upon its completion, the genius of Nicholas Clayton was

considered unrivaled and he was soon sought-after by the wealthiest men in

town.

Clayton was next hired by Colonel W.L. Moody

in 1883 to rebuild his fire-ravaged property on the northwest corner of Strand and 22nd. Although similar in form to

the Greenleve Block building, with four stories, an elaborate cornice, and a

showy cast-iron façade, Moody’s building was entirely unique and attributable

to Clayton only by its grandness and attention to detail. Inlaid panels of multi-colored

tiles established depth in the façade and highlighted the large windows, and

the involved brickwork and terra cotta finish gave the final result Clayton’s

trademark texture.

Clayton was next hired by Colonel W.L. Moody

in 1883 to rebuild his fire-ravaged property on the northwest corner of Strand and 22nd. Although similar in form to

the Greenleve Block building, with four stories, an elaborate cornice, and a

showy cast-iron façade, Moody’s building was entirely unique and attributable

to Clayton only by its grandness and attention to detail. Inlaid panels of multi-colored

tiles established depth in the façade and highlighted the large windows, and

the involved brickwork and terra cotta finish gave the final result Clayton’s

trademark texture.

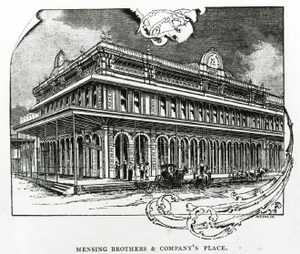

Meanwhile, the Mallory Produce building just

west of 21st Street

had burned again in 1881, but fortunately this time it was able to be repaired

instead of entirely rebuilt. Shortly after the repairs were complete,

construction on the Mensing Brothers and Company Building (2118-2128) next door

to the west was begun in 1882. Although only two stories, the corner building

featured rounded archways across the two sides of its street-level arcade and

the brick was stuccoed for a smooth stone finish. Inside, the building housed

one of the largest cotton factors and grocers, with a large part of the second

floor dedicated as the cotton sample and auction room.

But it was not until the end  of the decade

that anyone dared rival the staggering designs of Clayton, when another noted Galveston architect named

Alfred Muller completed the City Hall building in 1888. The building faced the Strand but was placed directly in the middle of 20th Street

to allow for traffic around its perimeter. Of stunning Gothic design,

of the decade

that anyone dared rival the staggering designs of Clayton, when another noted Galveston architect named

Alfred Muller completed the City Hall building in 1888. The building faced the Strand but was placed directly in the middle of 20th Street

to allow for traffic around its perimeter. Of stunning Gothic design,  the

building was home to a marketplace on the ground level where local farmers and

fishermen would sell their goods; the second and third floors were used for

municipal activities and the offices of city officials.

the

building was home to a marketplace on the ground level where local farmers and

fishermen would sell their goods; the second and third floors were used for

municipal activities and the offices of city officials.

By the 1890s the Strand was nearly saturated

save for a gaping hole at the end of 25th Street where the Gulf,

Colorado, and Santa Fe Railroad building had previously stood before it was

destroyed by fire in 1891. But the ensuing decade would fill in the last

remaining gaps and officially complete the notable architectural alley that

remains today. In 1890 the private banking firm of Adoue & Loubit sought

again the mastermind of Nicholas Clayton for their building on the northwest

corner of 21st Street. He managed to reign in his artistry and opt

for a modestly involved design for the building—perhaps so that it purposely

did not reveal that its residents were one of the largest financial operations

in the city at the time.

Across the street and a block to the east,

the John D. Rogers Building (2013-2019) between 20th and 21st

brought closure to that particular block in 1894. Historians assume that

although Rogers left an indelible mark on the building by way of having his

initials emblazoned on the east cornice, he most likely built the simple, stoic

building as an investment property. It was immediately occupied by an importing

company despite the fact that Rogers was a successful cotton merchant and owned

a large manufacturing company.

Across the street and a block to the east,

the John D. Rogers Building (2013-2019) between 20th and 21st

brought closure to that particular block in 1894. Historians assume that

although Rogers left an indelible mark on the building by way of having his

initials emblazoned on the east cornice, he most likely built the simple, stoic

building as an investment property. It was immediately occupied by an importing

company despite the fact that Rogers was a successful cotton merchant and owned

a large manufacturing company.

In 1895, just when Galveston thought they had

seen the best of Nicholas J. Clayton, he wowed yet again with his neo-Renaissance

rebuild of the Hutchings & Sealy bank on the northeast corner of 24th

Street. Utilizing a rare yellow brick and impressive granite, palatial columns

rose the entire height of its three stories. Numbers carved into the 24th

Street side represent the year the firm moved to Galveston, 1854, as well as

the year of the building’s construction.

On the Strand side, the names “Hutchings” and

“Sealy” over two distinct entrances reveal that the building is actually two

separate properties built as one, with a large atrium between them that reaches

skyward—it provided both air flow and natural light to the expanse of the

building.

Finally in 1898, the James Fadden Building

(2410-2412) would become not only the last building of this era ever erected,

but also the last notable work of Nicholas Clayton, whose fame and financial

situation would plummet shortly thereafter although he did continue to work

until his death in 1916. It was a much scaled-down version of his other, more

monumental designs, but Clayton still managed to make the building unmistakably

his with Roman columns, ornamental brickwork, and a

cornice that disguises the false-front of a nonexistent third floor.

Finally in 1898, the James Fadden Building

(2410-2412) would become not only the last building of this era ever erected,

but also the last notable work of Nicholas Clayton, whose fame and financial

situation would plummet shortly thereafter although he did continue to work

until his death in 1916. It was a much scaled-down version of his other, more

monumental designs, but Clayton still managed to make the building unmistakably

his with Roman columns, ornamental brickwork, and a

cornice that disguises the false-front of a nonexistent third floor.

Most certainly, the last two decades of the

19th Century were ones of a feeling of invincibility for the Strand

and the city. As the new century approached, the population more than doubled

to nearly forty-five thousand yet even still Galveston claimed the per capita

rating of the second wealthiest city in the nation, second only to Newport,

Rhode Island—the home of the Vanderbilt’s. It was a city of potential with a

street of plenty. The only thing that could stop Galveston’s meteoric rise was

the one thing that no one ever saw coming.

Chapter 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7- 8 - 9 - 10 -11 - 12