In 1976 Galveston applied to the United States

Department of the Interior for recognition of the Strand District on the

National Register of Historic Places. On the nomination form in the “Statement

of Significance,” Architectural Historian Carolyn Pitts of the National Park

Service wrote, “The hurricane of 1900 caused much destruction along The Strand,

but it was the development of the Houston Ship Channel and the lack of

development in Galveston’s harbor which brought an end to both Galveston’s

prosperity and the prominence of The Strand.”

Somehow over the last forty years that

narrative has been lost, and modern historians explain the discrepancy between

19th Century Galveston and 21st

Century Galveston

by perpetuating the myth that The Great Storm annihilated the city’s commercial

prospects. This inaccuracy also carries with it the assumption that Galveston has always been

the resort town that it is today, when in reality tourism was not perfunctory

but rather a slow and unplanned transition prompted by the construction of the

Seawall and its subsequent Boulevard. Fortunately even though history can

sometimes lie, numbers never do.

Somehow over the last forty years that

narrative has been lost, and modern historians explain the discrepancy between

19th Century Galveston and 21st

Century Galveston

by perpetuating the myth that The Great Storm annihilated the city’s commercial

prospects. This inaccuracy also carries with it the assumption that Galveston has always been

the resort town that it is today, when in reality tourism was not perfunctory

but rather a slow and unplanned transition prompted by the construction of the

Seawall and its subsequent Boulevard. Fortunately even though history can

sometimes lie, numbers never do.

Property damage from the storm both public

and private was estimated at over $30 million. The Central Relief Committee was

formed the day after the storm and oversaw citywide recovery efforts and

fundraising. Their final report listed gross receipts of only $1.2 million in

donations. The people of Galveston helped

themselves, led by the insatiable tenacity of the city’s commercial enterprises

and their monumental buildings on the Strand

that stood stoically among the rubble of the battered city.

Although every building on the Strand was at the very least recognizable in the

aftermath of the storm, the first levels had been completely submerged by the

storm surge that emptied them of their contents and left behind a black slimy

sludge that coated the walls and floors. Many of them were gutted completely

and debris was piled up along the street. Wagons rode by piled with bodies,

stark reminders that were also motivation to keep moving.

The storm decimated the rail bridge over the

bay, the only connection between Galveston

and the mainland, but it was completely repaired in eleven days. The port was

open for commerce in two weeks. On October 15th, five weeks after

the storm, it set a record for the most bales of cotton shipped out of the

harbor in one day—30,000. Within three months, the twenty-foot high, three-mile

long wall of debris was completely gone by way of either dismantling or fire.

Business alliances had formed among Galveston’s elite in the late 19th Century that

cooperatively spearheaded efforts to sway legislative and professional

interests toward Galveston

and the port. After the storm, the Deep Water Committee, the Wharf Board, and

the Cotton Exchange worked incessantly to expand the port and wielded the kind

of determination only found in tragedy. They did not only aim to maintain

consistent increases in cotton, but also desired to expand the port’s portfolio

of exports. Grains from the Midwest, lumber from the Southwest, minerals from Colorado, Missouri, Kansas, and Arkansas,

flour from the north, oil—if it was west of Texas they wanted it.

The complete destruction of the wharf made

way for a complete re-design that sprawled sixty acres along the harbor.

Entirely covered, with docking areas for up to ninety ships, the incredibly

efficient wharf incorporated electricity into every available aspect of the

loading and unloading process. Electric conveyors would feed directly onto

ships from the grain elevator; a large vessel could be loaded in under an hour.

Rail cars with electric motors took cargo from the wharf to the rail yard along

a labyrinth of tracks controlled by electric switches.

When business closed for the 1902 fiscal

year, the port of Galveston accounted a new record in foreign export value with

$99 million. The next year they topped that by an additional $5 million and

were the only port in the nation to exceed their previous high; the $400

million total value of freight handled

in 1903 also shattered its previous record.

When business closed for the 1902 fiscal

year, the port of Galveston accounted a new record in foreign export value with

$99 million. The next year they topped that by an additional $5 million and

were the only port in the nation to exceed their previous high; the $400

million total value of freight handled

in 1903 also shattered its previous record.

By 1908, Galveston had advanced more quickly

than any other Gulf port over the last decade—total revenue had increased 140%

from 1898 and 360% from 1894. Galveston also held the world record for the

amount of cotton received in a port in one day. By 1912, combined imports and

exports of the port of Galveston were $300 million, second only to the

unreachable New York and nearly $40 million more than New Orleans.

All the while, this commercial success

permeated the civic aspects of the city and at times outright persuaded

municipalities to invest in improvements. Determined to forever withstand any

future storms and prevent another disaster, the Seawall was built between 1902

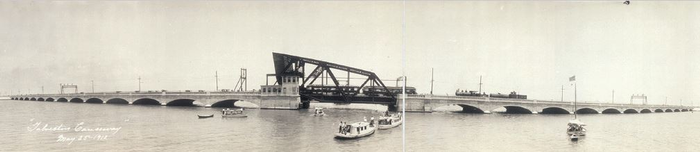

and 1904, followed by the seven year long grade-raising. Streets were repaved

and a causeway was completed in 1912 that allowed automobiles to travel to the

island for the first time ever. The sum total of all of these improvements

registered nearly $8 million, and much of it was financed by bonds purchased by

Galveston residents.

While the entrepreneurial minds within the

city can certainly be credited with the resplendent rise of Galveston in the

early 1900s, logistically much of it was just geography. Galveston was the

closest port to the western half of the United States by 400 miles; the city’s

success merely proved the necessity of a well-developed Texas port. The only

location that had any chance of truly competing with Galveston was Houston, but

their spattering of residents had spent the last forty years quarreling over

the idea of dredging the natural waterway to the Gulf to make a ship channel.

But Houston steadily continued its slow

maturation while Galveston was preoccupied with the building of a

seventeen-foot high Seawall and elevating 500 city blocks to protect them from

future obliteration, until 1910 when Houston finally found itself up to the task

and voted to approve the $1.25 million needed to dredge the channel. Four years

later on November 10, 1914, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed the Houston

Ship Channel open. Galveston would never be the same, and neither would The

Strand.

But Houston steadily continued its slow

maturation while Galveston was preoccupied with the building of a

seventeen-foot high Seawall and elevating 500 city blocks to protect them from

future obliteration, until 1910 when Houston finally found itself up to the task

and voted to approve the $1.25 million needed to dredge the channel. Four years

later on November 10, 1914, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed the Houston

Ship Channel open. Galveston would never be the same, and neither would The

Strand.

Prior to 1914, city directories began with a

lofty introduction of pages upon pages lauding Galveston’s prosperity,

prospects, and potential. Later the directory merely read, “In presenting the

1919 edition of the Galveston City Directory the publishers feel that no more

appropriate introduction can be offered than the assurance that nothing has

been omitted on their part to insure accuracy and completeness. The Directory

contains 592 pages.” The directories also reveal the source of this severely

deflated confidence—every third listing along Strand Street reads “Vacant,” and

the occupied addresses portray a downtown resembling that of a sleepy country

town. Grocers and produce houses were accompanied by one or two remaining

cotton factors, a bank, and miscellaneous retailers.

As Galveston took its respite, the nation

found itself entrenched in an ongoing battle over the perils of alcohol and a

powerful movement took hold that aimed to enact a nationwide ban. Galveston

County moved to support the movement and went dry in 1918

to show solidarity with the cause. Two years later Prohibition was passed, and

the slumbering Strand would awaken to a renewed purpose when alternate

enterprises would once again find an efficient use for buildings snuggled up to

a friendly, international harbor.

Chapter 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7- 8 - 9 - 10 -11 - 12